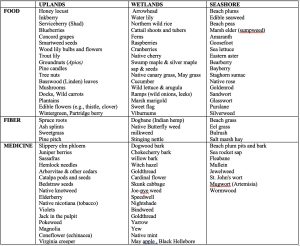

The Algonquians in New England used their Woodland lithic, ceramic, bone, shell, wood, and fiber technologies to accomplish a seasonal cycle of hunting, fishing, gathering, clamming, and cultivating crops. The proximity of wetland, upland, and estuary biomes with ample resources enabled them to maintain a mixed economy. The seasonal cycle followed the availability of subsistence resources, with trapping, ice fishing, specialized hunting, and crafting in winter, supported by preserved surpluses of food. Spring was the time for sugaring, exploiting fish runs on tidal rivers, planting corn and vegetables, and gathering eggs and feathers. Summer invited salt-water fishing, shellfish gathering, gardening, honey collecting, root gathering, and fruit and berry picking. And fall was a time for harvesting, nut gathering, hunting, trading, visiting, raiding, preserving food, winterizing, and caching resources.

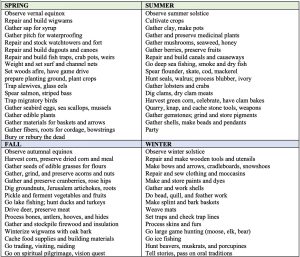

Seasonal activities

Seasonal round calendar[1]

Division of Labor

Division of labor was by sex, age, and talent. Basically, men hunted, fished, trapped, made canoes, quarried stone, prepared land for tillage, and helped erect wigwam frames and process meat and fish. Women planted, cultivated, gathered shellfish and wild food, wove mats, collected firewood, carried water, furnished wigwams, harvested crops, preserved foodstuffs, and processed corn, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Everyone contributed to child rearing, processing hides and fibers, making cordage, paints and dyes, providing clothing, and making clay pots, beads, and baskets.[2]

Champlain commented on the division of labor by sex among the Algonquians:[3]

There is a moderate number of pleasing and pretty girls, in respect to figure, color, and expression, all being in harmony. …these have almost the entire care of the house and work; namely, they till the land, plant the Indian corn, lay up a store of wood for the winter, beat the hemp and spin it, making from it the thread fishing nets and other useful things. The women harvest the corn, house it, prepare it for eating, and attend to household matters. Moreover, they are expected to attend their husbands from place to place in the fields, filling the office of pack-mule in carrying the baggage, and to do a thousand other things. All the men do is to hunt for deer and other animals, fish, make their cabins, and go to war….

So gathering shellfish was women’s work and everything to do with plants. Division of agricultural labor followed the pattern for village life and hunting and gathering. Men and boys cleared the fields, removed rocks and stumps, and made mounds (or cornrows if planting in alluvial soils), while women and girls planted, weeded, reaped, and processed the harvest. In 1629 William Wood observed Indigenous women gathering lobsters, wading out from Plymouth’s beaches to gather them by hand. Lobsters were so plentiful that the bodies were used mainly as bait.[4]

Women goe to get Lobsters for their husbands, wherewith they baite their hookes when they goe a fishing for Basse or Codfish. This is an every dayes walke, be the weather cold or hot, the waters rough or calm, they must dive sometimes over head and eares for a Lobster, which often shakes them by their hands with a churlish nippe, and bids them adieu. The tide being spent, [the women] trudge home…, with a hundred weight of Lobsters at their backs, and if none, a hundred scoules meet them at home….

In Summer these Indian women when Lobsters be in their plenty and prime, they drie them to keepe for Winter, erecting scaffolds in the hot sun-shine, making fires likewise underneath then, by whose smoake the flies are expelled, till the substance remain hard and drie. In this manner they drie Basse and other fishes without salt, cutting them very thinne to dray suddainely, before the flies spoile them, or the raine moist them, having a speciall care to hang them in the smoakie houses, the nigh and dankish weather.

All human societies allocate the work of making a living and maintaining an economy, first by age and sex and then by other criteria (such as skill, talent, avocation, education, training, social status, class, and caste). Artisans, herbalists, healers, elite warriors, shamans, and leaders chosen from eligible high-ranking families, for example, potentially enjoyed special status independently of their sex.

Much as we would like to believe it, however, it is not true that hunting and gathering societies are and were naturally more egalitarian or had greater gender equality. Hunter-gatherers practice gender segregation in some social contexts, e.g., exclusive membership in a sororal or fraternal organization or a secret society, and taboos associated with female sexual status (menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth). Depending on the type of kinship system, and independently of the type of economy, higher jural and military authority is most often reserved to males. Some hunting and gathering societies were authoritarian, enacted bitter internal rivalries, and kept slaves. Both competition and cooperation are operative in all human societies. Domestic violence is present universally, furthermore, independently of the type of economy or level of social organization. So, the idea that Indigenous people living in pre-modern communities automatically have less social stratification, and therefore more equality and greater social harmony, is a fiction.

Among the Algonquians, while some jobs were shared overall, some specific tasks were narrowly defined and meted out by gender. Men traditionally did not collect or plant seeds or till crops, for example, and women traditionally did not quarry and knap stone or make arrows. The status of a woman was based on her position within her family and the family’s inherited or customary social status, or rank and prestige, within the community. Sachems, sagamores, and saunksquas–male and female leaders, usually came from families inter-generationally slated for leadership.

Hunting

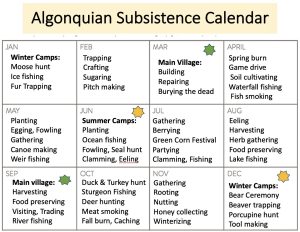

Much of what we know about Algonquian ways of making a living comes from the accounts of the earliest European explorers, such as Samuel de Champlain, who explored the Northeast between 1603 and 1635, and early settlers, such as William Bradford and Edward Winslow of Plymouth Colony, William Wood and Francis Higginson of Salem Village, Daniel Gookin and John Eliot of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and others. A drawing from Champlain’s 1604 expedition, for example, shows a deer hunt in the lower Merrimack Valley in which beaters are driving game animals into a kill zone with fence traps, later described by William Bradford as a “driving yard”.

Champlain’s illustration of a cooperative deer hunt[5]

According to Bradford:[6]

A well known resort for moose and deer was selected and enclosed on two sides of a triangle, forming a figure like the letter V. At the apex of the angle, a space was left open for the game to pass through, and near this open space, the marksmen were placed to shoot what game might pass. The less experienced of the Indians were sent out to beat the woods, and to drive the game within the enclosure. Once within this, the drivers closed up, and the game attempting to escape through the open space, were shot down by the marksmen. In this way, they were often successful in taking moose and deer. They often set snares of ropes at the open space of the drive, which being attached to the tops of saplings bent down for the purpose, would lift the game high in the air…

Game drives were conducted in fall and spring in connection with the practice of selectively burning the woods through controlled fires. Specialized hunting in the wintertime among Abenaki-speaking peoples, including the Pennacook and the Pawtucket of Essex County, included beaver, moose, and porcupine; a bear hunt for an annual bear sacrifice ceremony; and traplines for fur-bearing animals. But, as Champlain noted in his journal, the “Almouchiquois” of the Massachusetts coast were really only interested in fishing and farming.[7]

Hunting was important in other ways. Successfully hunting a deer was a step in a boy’s coming of age and often a prerequisite for marriage. Animal by-products (antlers, bones, hooves, teeth, hides, feathers, etc.) all had important uses in Algonquian life. A warrior’s rank could be conveyed in the bear claws or beaver teeth he wore in his necklace, the feathers in his hair, or the squirrel tails adorning his clothing. Bird wing fans and deer hoof rattles were sacred regalia, accessories at powwows. A shaman’s kit included polished gastroliths–small smooth stones from the gizzards of birds. The act of hunting was itself a spiritual enterprise involving a transaction between the hunter and the animal. The hunter displayed respect for the animal by wearing a special hunting shirt beautified with parts of the animal being hunted and by using spiritually powerful hunting gear, especially quartz projectile points. The animal or its animal master reciprocated by symbolically granting permission for the kill.

Gathering

Harvesting wild rice[8]

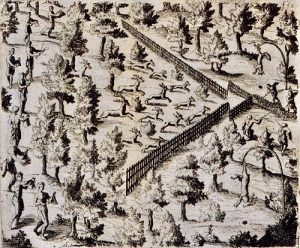

Algonquian women gathered many wild foods and medicinal herbs, including vegetables, roots, fruits, berries, fungi, edible seaweed, native wild grasses with starchy grains, such as maygrass (ubiquitous in fields and backyards in Essex County today), wild rice (which still grows upstream in some Essex County rivers), and plants with starchy edible stalks, such as cattails and staghorn sumac (both still here as well). Almost every native plant you see here today was useful to Indigenous people in some way as food, fiber, medicine, spiritual substance, or art medium.

Chart of some plant foods women gathered[9]

Women led community ceremonies of thanksgiving following each important wild plant harvest. Thanks was given again each time anything made from a harvested plant or animal was used. By now every reader must know that the traditional American story of Thanksgiving is not how it happened and that the Wampanoag and others today celebrate it as a Day of Mourning. The reality is that there were 92 armed warriors (and no women) with Massasoit that day at Plymouth and they came in strength because they heard musket fire. Bradley’s militia had fired their weapons in a parade salute and the Wampanoags weren’t sure what that meant. The warriors provided the deer meat. The Pilgrims contributed ducks and swans (no turkeys, and no pies, pumpkin or otherwise). The feasting lasted for three days and the encounter went down in history as amicable.

Seafood Industries

Eastern Algonquian life centered on seafood harvesting and agriculture, which became more important than hunting and trapping. Champlain ruled out Cape Ann as a possible capitol for New France because of this, as the French sought to finance their colony through the fur trade. Fish and shellfish of all kinds were plentiful by all accounts, including Francis Higginson’s description of Cape Ann’s and Salem-Beverly’s fisheries as he found them in 1629:[10]

The aboundance of Sea-Fish are almost beyond beleeving, and sure I should scarce have beleeved it except I had seene it with mine owne Eyes. I saw great store of Whales, and Grampusse, and such aboundance of Makerils that it would astonish one to behold, likewise Cod-Fish aboundance on the Coast, and in their season are plentifully taken. There is a Fish called a Basse, a most sweet and wholesome Fish as ever I did eat, it is altogether as good as our fresh Sammon…. Of this Fish our Fishers take many hundreds together…yea, their Nets ordinarily take more then they are able to hale [haul] to Land…. And besides Basse we take plenty of Scate and Thornbacke, and aboundance of Lobsters. Also here is aboundance of Herring, Turbut, Sturgion, Cuskes, Hadocks, Mullets, Eeles, Crabs, Muskles and Oysters.

Fish proteins were a mainstay in the Algonquian diet. They used weirs, nets, cast nets, spears, harpoons, hooks and lines, and basketry traps to harvest fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. They constructed weirs in rivers, streams, and estuaries, erecting barriers of sticks, woven fences, or stone vees that slowed down or channeled migratory fish, and they made eel traps and crab pots. More than deep-sea fishing, Eastern Algonquians relied on anadromous fish, such as sturgeon, salmon, alewives or shad (river herring), smelts, and striped bass coming in to fresh water rivers and streams to spawn. They also favored catadromous species going from fresh to salt water to spawn, especially the Atlantic Eel. Both men and women prized soft cured eel skins as moccasin ties, hair ribbons, headdress fasteners, tump lines, cradleboard ties, and necklaces for amulets, medicine bags, and tobacco pouches. The people trapped and speared fish at different stages of their life cycles in lakes, at waterfalls, in freshwater coves, in estuaries (brackish river outlets), and in the sea.

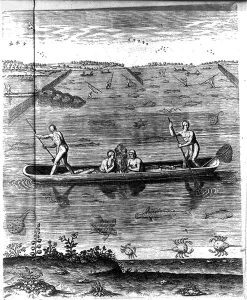

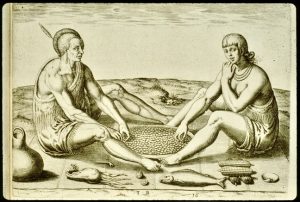

DeBry’s engraving of Indians fishing[11]

Writing in 1638, John Josselyn reports that the Algonquians speared sturgeon in the Merrimack River from canoes by the lure of torchlight at night and collected their eggs—caviar. Some indigenous people living traditionally today gather caviar by plunging young evergreen trees tip-first into the places where sturgeon spawn, where millions of eggs coat all underwater surfaces. The fishers then draw up the trees into their canoes to collect the caviar clinging to the needles. The Algonquians also caught large fish and marine mammals (including sea bass, tuna, bluefish, swordfish, porpoises, harbor seals, walruses, and whales), using harpoons with detachable heads. According to Josselyn:[12]

The Bass and Blue-fish they take in Harbors and at the mouth of barred rivers, being in their canoes, striking them with their fishgig, a kind of dart or staff, to the lower end whereof they fasten a sharp, jagged bone with a string fastened to it, as soon as the fish is struck, they pull away the staff, leaving the bony head in the fishes body and fasten the other end to the canoe. Thus they will haul after them to shore half a dozen or half a score great fishes.

Samuel de Champlain reported how the people used the shells and boney tails of horseshoe crabs as tools and added the bodies, along with lobster bodies, to their corn hills as fertilizer:[13]

[T]here are a great many siguenocs [horseshoe crabs], which is a fish with a shell on its back like the tortoise, yet different, there being in the middle a row of little prickles, of the colour of a dead leaf, like the rest of the fish. At the end of this shell, there is another still smaller [shell], bordered by very sharp points. The length of the tail varies according to their size. With the end of it, these people point their arrows….The largest specimen of this fish that I saw was a foot broad, and a foot and a half long.

Shells of horseshoe crabs were sewn together to make small purses or cases or canteens for carrying trail food, worn over the shoulder or on a belt. By all accounts both the abundance and sizes of all species of fish, shellfish, and aquatic arthropods greatly exceeded what we see today. The Algonquians smoked meat, fish, and shellfish meats on stages and racks to preserve for winter meals and trade goods.

The Broiling of their fish[14]

They ate shrimp, crabs, lobsters, scallops, oysters, clams, quahogs, mussels, sea snails, and moon snails. Clams and mussels were especially important as survival and quality of life foods, for they are plentiful in all seasons, easy to obtain, and can be eaten fresh, cooked, or dried. The great depth of shell heaps all along the New England shore testify to the importance of this food source over thousands of years.[15] In Algonquian times, bands shared access to rich clam beds to ensure an adequate year-round supply of animal protein for everyone. Gathering shellfish does not require special skills or strength. Elderly and infirm or disabled individuals would camp near clam flats to help their families keep them fed. Midden burials on the shore have been found to contain the remains of aged individuals.

For summer gardens at the shore, people sometimes carried arable soil in baskets to lay on top of leveled shell heaps in the dunes, building a ten- or twelve-inch layer of earth to plant in. The shells would have stabilized and sweetened the the soil. Shell middens, corn hills, and Late Woodland burials at the western end of Coffin’s Beach were reported by N. Carleton Phillips (1940). Evidence of corn hills may still exist in the dunes south of the road. Phillips also described corn hills on Cole’s Island in West Gloucester.[16]

Oyster midden topped with imported soil on Great Neck, Ipswich

F. W. Putnam (1869) first reported on shell heaps in Essex County. Later, Marshall Saville (1920), Frank Speck and Frederick Johnson, and N. Carleton Phillips (1940) all reported and excavated extensive middens on Cape Ann (Lepionka 2013).[17] For example, Speck explored a large midden in Riverview beside his cottage in Curtis Cove (Blankenship 2012; Dodge 1991), and he and his student Frederick Johnson excavated a large midden on Pearce Island. Shell middens also abound in Essex and Ipswich, as seen, for example, in LeBaron’s 1874 Archaeological Atlas of Castle Neck, Ipswich, and in Ripley Bullen’s excavation of the Neck Creek Shell Heap in Little Neck (1947). The Harvard Peabody Museum has extensive collections from other shell heaps near the mouths of rivers emptying into Plum Island Sound in Ipswich and Newbury (e.g., Egypt River, Eagle Hill, Castle Hill, Turkey Hill).[18]

Horticulture

Algonquians in New England practiced intensive horticulture and basic agriculture with seed-bearing plants. Horticulture is gardening, or cultivating fruits, vegetables, herbs, trees, or shrubs. Intensive horticulture involves cultivating gardens or groves in three ways:

1) protecting stands of wild plants;

2) gardening with transplanted young wild plants; and

3) planting roots, cuttings, or seeds from wild plants.

These practices often led to domestication, in which the survival and reproduction of a variety or a species is determined by human agency rather than by natural selection.[19] Indigenous people in Eastern North America practiced intensive horticulture based on the cultivation of native beans, squashes, melons, potatoes, peas, tobacco, and other plants, such as chenopodiums and sunflowers, even before they received maize.[20] Gardens were made by companion planting in raised beds.

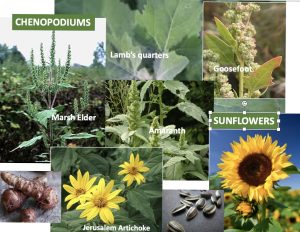

Chenopodiums and sunflowers[21]

Native beans in New England include navy beans and pea beans; native squashes, pumpkins, and melons include acorn squash, crookneck yellow squash, musk melon, and a dwarf watermelon. Nicotiana rustica and Nicotiana alata are the two native varieties of tobacco here.

In contrast to horticulture, basic agriculture, is the mass cultivation of domesticated seed crops, such as corn, for the purpose of producing a surplus. Intensive agriculture is seed crop cultivation on a large scale, using irrigation, fertilization, crop rotation, and other methods for achieving high yields. Thus, intensive agriculture involves a greater amount of land, labor, and planning than is required for intensive horticulture or basic agriculture. Algonquian farmers practiced basic agriculture and used a system similar to crop rotation, allowing soils to recover their fertility by leaving them unplanted for as long as 20 or 25 years, but they did not routinely use irrigation or fertilizer.

Silviculture

Horticultural practices involving trees and forest management–practices intended to manage or improve forested land and tree products–is called silviculture.[22] Algonquians in the Northeast created oak-hickory and oak-pine groves and forests to conserve nut-bearing trees, trees with important bark, and the berry- and fruit-bearing forbs growing in their understories. They also harvested trees in a pattern that left grassy clearings between them, creating a kind of parkland with evenly spaced trees. All the early Spanish, French, English, and Dutch explorers and settlers remarked on seeing parklands all along the coast where they had expected to find continuous dense forests.[23]

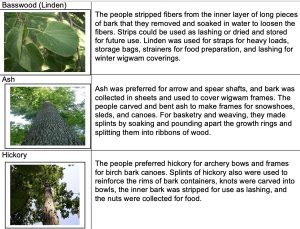

Algonquians made elaborate use of woods and fibers during the Woodland period and into the time of European contact. They ate many nut-based meals or flours, for example, gathered wild honey, and collected tree sap from willows, maples, and birches to boil down for syrup. They poured the syrup into small birchbark forms to crystallize into cakes or candies. They also added the sweeteners to seed cakes, parched ground corn, acorn gruel, and trail mixes. Colonists were fascinated by the process of rendering syrup from sap; European uses of tree sap had extended only to making tar or pitch from pine resins for their navies. The Algonquians also used the comparatively soft woods of maple, pine, basswood, willow, and chestnut for carving poles, cots, spoons, bowls, cradleboards and other household items, and they conserved the trees they used. Cradleboards were adapted to serve as backpacks, sleds, and swings in addition to cradles and were decorated with carvings, dreamcatchers, fur, and beaded coverings. Mothers adjusted cradleboard bedding and closures seasonally and modified them to suit the child’s stage of development.

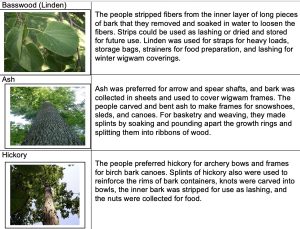

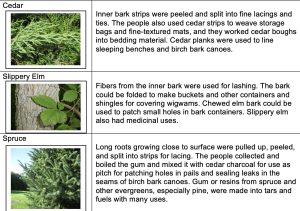

Some Trees Algonquians Used in Their Wood and Fiber Technologies[24]

Algonquian forest management practices may have contributed to the great diversity of mixed deciduous and conifer species growing in close proximity throughout coastal southern New England today. Within a single acre of Algonquian woodlot, for example, cleared of undergrowth (except for girdled or felled hardwood trees left to die and dry for firewood), one might find elms, oaks, ashes, nut trees (such as hickories, walnuts, chestnuts, beechnuts, and hazelnuts), maples, birches, and cedars growing side by side. Today, any mixed-species grove of old-growth trees was likely originally maintained and used by resident Algonquians.

Fire was commonly employed in harvesting trees. For dugout canoes, trees were weakened by controlled fire all around the base before being felled by stone axes close to the ground. Remains of base-burned trees taken for dugouts may still be seen in old growth forests in New England. The people also routinely burned off undergrowth around their settlements–creating a safe living space and new habitat for small game and birds and to keep ways open for travel, to detect any approaching enemies, and to stimulate nut-bearing trees and berry-producing shrubs and vines (such as grapes, blueberries, blackberries, huckleberries, etc.) to bear fruit. In fall burns, toasted pine cones could be left on the ground as winter fodder for deer. Expanses of fire-tolerant or fire-resistant trees today (e.g., pine, oak, mountain ash, beech) may have been created ages ago by Indigenous people. As a tool, fire also hardened wood, produced charcoal, made food safer to eat and more edible, smoked fish and meat, and heated stones for sweat houses and cooking. Fire thus was employed for many more uses than to clear land for planting grounds.[25]

Agriculture

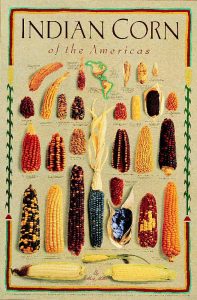

Algonquian basic agriculture was based on the domestication of maize (Zea mays).[26] Wild corn, teosinte, is a grass native to the Western Hemisphere with “ears” consisting of eight edible kernels. Indigenous people selectively bred teosinte and similar grasses to create domesticated varieties of “Indian corn” with larger ears and many more rows of kernels.

Zea Mays and varieties of Indian corn[27]

The domestication of grasses—corn, wheat, oats, rye, barley, sorghum, millet, and rice are all grasses—occurred as plants evolved to retain rather than release their seeds in response to human “predation”. Consequently, the plants could not disperse viable seed without human agency. In domestication, people—not nature—determine what traits are advantageous. People select desirable individuals or varieties and control their survival and reproduction. For example, Algonquians in the Northeast bred an early-maturing variety of maize by routinely selecting kernels from the first ears to form at the bottom of a stalk to save as seed corn for the following year. Even with early-maturing varieties, maize will not grow above 55°N, and soil temperatures must reach 50°F before it will germinate. Thus, Indigenous peoples in northern New England and Canada specialized as hunters and gatherers, while those in southern New England and the mid-Atlantic specialized in farming. It is these kinds of realities that have shaped the human story.[28]

Indigenous people living in the northern Mexican and Guatemalan highlands first cultivated maize as early as 8,000 years ago.[29] The practice spread both southward to Central and South America and northward to the Mississippi Valley and the Northeast.[30] According to Algonquian legends, crows carried kernels of corn to them from the southwest as a gift from their creator spirit.[31] Thus, agriculture in the Western Hemisphere is nearly as old as agriculture in the Eastern Hemisphere. Domestication was a global economic revolution made possible by climate change that favored the evolution and spread of domesticable plants and animals.[32] As it happens, other than the wolf dog, domesticable animals did not live in northeastern North America. As John Josselyn noted, “Tame Cattle they have none, excepting Lice, and Doggs of a wild breed that they bring up to hunt with.”

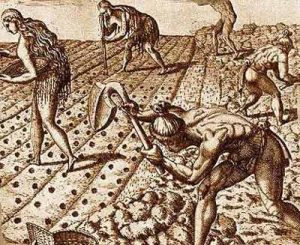

Agriculture provided high-calorie, high-protein legumes (peas, beans); cereal grains (corn); and starchy tubers (potatoes). In the Western Hemisphere beans and potatoes were independently domesticated three times: east of the Appalachians, in Mesoamerica, and in the Andes.[33] Europeans were surprised to discover Native plantations in New England. Champlain commented on them nearly everywhere he made landfall from Piscataqua Harbor in New Hampshire to Nauset Harbor on Cape Cod.[34]

Before reaching their wigwams we entered a field planted with Indian corn…. The corn was in flower and some five and a half feet in height. There was some less advanced, which they sow later. We saw an abundance of Brazilian [sic] beans, many edible squashes of various sizes, tobacco, and roots which they cultivate, the latter having the taste of artichoke…. There were also several fields not cultivated, for the reason that the Indians let them lie fallow.

Here there is much cleared land and many little hills, whereon the Indians cultivate corn and other grains on which they live. Here are likewise very fine vines, plenty of nut-trees, oaks, cypresses, and pines. All the inhabitants of this place are much given to agriculture, and lay up a store of Indian corn for the winter….

Detail from De Bry’s Engraving of Algonquians Planting in Virginia[35]

Farming Methods

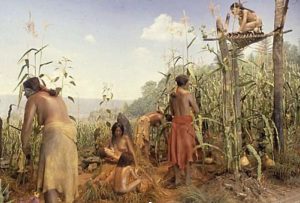

In New England, especially near the coast where wetlands dominate and bedrock is near the surface, exposed, or covered by only a shallow depth of soil, the Algonquians did companion planting in mounds.[36] Mounds increased the depth of soil and, raked up after each rain, could conserve moisture. In companion planting, corn stalks supported climbing beans, while winter squashes shaded and mulched the roots of the corn. This is known as the “three sisters” method. In cool springs, women germinated seeds in moist clay in leather pouches and planted the seedlings in the mounds. The people also grew Jerusalem artichokes (for their potato-like tubers), native sunflowers (for their seeds and oil), and other crops, such as cucumbers, peas, chenopodiums (e.g., amaranth, goosefoot, quinoa), and tobacco.[37]

Mounds and Three Sisters plantings[38]

According to Daniel Gookin, quoted in C.E. Potter, p. 109, Algonquians in New England began preparations for planting:

When the oak leaf became as large as a mouse’s ear [sic, he meant a moose’s ear]. This was their rule as given to the first settlers. They planted in rows, much the same as we do at present. The crows, which they called Kaukont, from the sound of its caw or screech, devoured the young corn, and to prevent the depredations of this and other birds, small lodges were built in the fields, in which the elder children watched, and the men themselves oftentimes. They did not kill these crows, as they held them as sacred, as their greatest benefactors. They had a belief, that a crow brought their first kernel of corn and a bean into the country from the southwest–a present from their Great Manit, “Kautantonwit’s” field, in the south west. From this kernel of corn, and this bean, they supposed they derived all their corn and beans. Hence, they thought the crow entitled to a share, and did not offer a bounty for his head, even though he might at times take more than was fairly his share.

European settlers were harder on the crows in their cornfields, offering bounties for them and also for the wolves that came to dig up the fish they were planting with the corn. The colonists did not share the Algonquian myth about corn and beans (which incidentally acknowledges the spread of maize cultivation from its origins among the Moundbuilders of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys to the southwest).

Tobacco was an important cultivar to the Algonquians. Despite our short growing season, native tobacco (Nicotiana) grows in New England as well as in Virginia but with a narrow-leaf, early-maturing, scented variety rather than the broad-leaf tobacco of the South. People dried the leaves and stems and crushed them into powder for smoking. Tobacco of any kind and in any form was a major object of Indigenous trade, as it was used, for example, in purification ceremonies, vision quests, votive offerings to spirits, and gift giving. Men and women used small stone, clay, wood, or corncob pipes to smoke small amounts of tobacco as an entheogen to enhance spiritual experience.[39] Exhalations of tobacco smoke were believed to send prayers aloft to the spirit world. Communal smoking—passing the pipe—was customary when sealing agreements, celebrating social events, facilitating communal meditation and prayer, and enhancing shamanic or curative experience.

Lorillard Hogshead[40]

The French explorer Jacques Cartier first reported the smoking of tobacco in North America in 1535.[41] The French used the term pétun for tobacco, from an Iroquoian word, and referred to the long ceremonial “peace pipe” as a calumet. After timber and furs, tobacco became the most important early export in European trade.[42] Champlain received a gift of tobacco from the Algonquians on Cape Ann. He reported that Algonquian agricultural practices included sowing successively for early and late harvests, allowing fields time to recover their fertility in a kind of crop rotation, planting cover crops, for example, canebrakes–for future production and as habitat for deer, and setting fire to fields and forest undergrowth twice a year.

In coastal New England the Algonquians farmed without irrigation on outflow terrains—hilly slopes that sluice rainwater and meltwater down to streams and the sea. They used “dry farming” methods to keep rainwater within the soil and prevent moisture from draining away before plants had a chance to absorb enough moisture to grow. Dry farming methods include contour planting—following the natural shape of the land—and planting in mounded or bermed rows perpendicular to the direction of groundwater outflow (called bunding).[43] Locating and tracking groundwater flows was practiced by native people throughout the Americas, even in areas with abundant surface water, and the Algonquians marked with stone the locations and directions of groundwater sources near the surface. Those stone features may still be seen today in undeveloped uplands in Essex County and throughout Massachusetts.[44]

Artist’s representation of harvesting corn[45]

Tisquantum’s Fertilizer

Contrary to legend the Algonquians did not routinely use fertilizer. In emergencies soil fertility could be extended through the use of fish waste and seaweed, which restore nitrogen and trace minerals to the soil. However, there is little archaeological evidence for routine use of fish in Native agriculture.[46] Also, carrying fish waste to fields was expensive in time, energy, and resources, and attracted wolves and other carnivores that would dig up the crop to get at the fish.[47] William Bradford’s classic account of the Patuxet Tisquantum (Squanto) showing the Pilgrims at Plymouth how to plant with fish, is about an emergency measure:[48]

Those that could began to plant their corn, in which service Squanto stood them in good stead, showing them how to plant it and cultivate it. He also told them that unless they got fish to manure this exhausted old soil, it would come to nothing, and he showed them that in the middle of April plenty of fish would come up the brook by which they had begun to build, and he taught them how to catch it and where to get other necessary provisions; all of which they found to be true by experience. They sowed some English seed, some wheat and pease, but it came to no good either because of the badness of the seed or the lateness of the season….

So, in their first spring the surviving Plymouth colonists were late attempting to plant imported seed in uncultivated, infertile soil. Dead and dying fish readily available nearby—alewives (river herring) die far upstream after spawning, littering the banks of streams—could be collected by the basketful and carried to the planting ground to augment the soil. This is what “Squanto” was showing them.

And that’s another thing about history. It isn’t absolutely true—is it—but reflects the interests and needs of the people telling the story and those hearing it. As a consequence, we get George Washington’s cherry tree in one generation and in a later generation his wooden dentures. Centuries of Christopher Columbus worship get replaced by news of adventurers we never heard of before who preceded him to America, and for some the national holiday of Thanksgiving becomes a Day of Mourning. We get new facts from time to time, but the same old facts periodically get selectively reinterpreted by historians writing as kingmakers or iconoclasts, whistleblowers or redeemers. For, I think that except in hindsight, for better or worse, we don’t really know what’s really happening to us most of the time, much less what our impacts on the future might be.

In any case, the “slash and burn” method of preparing planting grounds, or swiddening, provided natural fertilizer from the potash in the burned wood.[49] This method involves clearing land by selectively felling and burning trees upon their stumps and then inter-planting crops in mounds between the trunks.[50] As clearings grew, they removed roots and rocks to piles at the outer edges. In Les Voyages, Champlain describes the practice of slash and burn agriculture as it was practiced along the New England coast (and is still being practiced among indigenous subsistence farmers in South America today):[51]

Some of the land was already cleared up, and they were constantly making clearings. Their mode of doing it is as follows: After cutting down the trees at the distance of three feet from the ground, they burn the branches upon the trunk and then plant their corn between the stumps, in course of time tearing up also the roots.

Fields were cultivated until the soil became infertile and then were left fallow for as long as a generation (20-25 years) to recover their fertility. Corn is a heavy nitrogen feeder and depletes soil within two or three seasons. Algonquians moved their settlements every few years to clear new land or to be nearer to whatever fields they were putting into production in a given year. This “mobile farming” confused the colonists, who mistakenly assumed that people were abandoning their villages.[52] The English also did not understand the Algonquian practice of preparing much more land for cultivation than they planted. The purpose was to improve the soil for future planting, as needed, but the sight of acres of land prepared for cultivation but left unmanured and unplanted motivated many colonists, for whom there could never be too much surplus, to acquire or appropriate them.[53] Some of the first English plantations in Massachusetts (e.g., Wessacoucon at Newbury and Gloster in Gloucester) were established on “the hoed ground” or “the scorched plain” of the Indigenous farmers.

Dried foodstuffs

The Algonquians produced surpluses of plant and animal foodstuffs that they preserved for future use and for trade through drying, smoking, fermenting, and, in winter, cold storage.[54] They harvested great amounts of maize, and dried the ears in 12- to 20-bushel heaps on fiber mats. Dried surplus corn was traded or stored for winter in clay pots and baskets in underground storage pits lined with grasses or cedar boughs to prevent mildew or spoiling.[55] Algonquian cooked dishes always included corn: for example, a corn mush called samp (nausamp), which could also be baked into corn bread (the origin of hush puppies), parched corn (nokehick) and corn boiled with squash and beans in succotash.[56] Green corn was also a staple in community celebratory meals known as clambakes.[57] Because of corn’s value as a staple food, the Massachusetts Puritans commodified it as a form of currency and fixed its price.[58]

Algonquian couple in Maryland enjoying a meal[59]

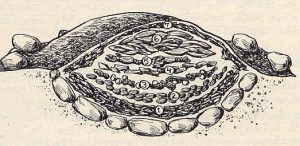

Clambake[60]

Surpluses of corn were carefully maintained, as Thomas Morton observed in 1637:[61]

These people are not without providence, though they be uncivilized, but are carefull to preserve foede [food]to store against winter; which is the corne that they laboure and dresse in the summer. And, although they eate freely of it, while it is growinge, yet have they a care to keepe a convenient portion thereof to releeve them in the dead of winter,…which they put under ground. Their barnes are holes made in the earth, that will hold a Hogshead of corne a peece [apiece] in them. In these (when their corne is out of the huske and well dried) they lay their store in greate baskets which they make of Sparke [rush]….

The Eastern Algonquians living in Essex County at the time of European Contact were the Pennacook-Pawtucket, and they were fishing, lobstering, clamming, crabbing, eeling, canoeing, weaving, potting, hunting, fowling, gathering, gardening, cultivating field crops, and managing forests here. But now new questions arise: Who were the Pawtucket, and where did they come from. And where did they live exactly? How can we locate their villages?

Next: Who were the Pawtucket and where did they come from?

Notes and References

[1] This calendar is hypothetical, a composite giving a general idea of what Algonquian seasonal rounds were like for subsistence procurement in southern New England. The yellow suns are the solstices and green ones are the equinoxes. Such a calendar I hope also suggests the sophisticated logistics that would have been involved in maximizing such a mixed economy over time.

Secondary sources for Algonquian seasonal subsistence and division of labor include M. K. Bennett (1955) The food economy of the New England Indians, 1605-1675, in Journal of Political Economy 63(5): 369-397; Kathleen Bragdon’s (1999) Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650, and Gender as a Social Category in Native Southern New England, in Ethnohistory 43 (4); Colin Calloway (1991) Dawnland Encounters; John DeForest (1851) The History of the Indians of Connecticut; John Reid and Emerson Baker (2008) Essays on Northeastern North America, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries; and Carolyn Merchant (1989) Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England.

See also Doughty, Christopher E., 2010, The development of agriculture in the Americas: An ecological perspective, in Ecosphere 1: 21. Washington, DC: Ecological Society of America. Coastal Algonquians retained a mixed economy, while the inland Iroquoian people specialized in growing corn. For a perspective on Iroquois specialization in agriculture, see https://theiroquoisstory.weebly.com/iroquois-food-and-agriculture.html.

[2] For a discussion of division of labor by sex in horticultural and agricultural societies, see Carolyn Merchant’s book Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England (1989). Another source is Kathleen Bragdon, for example, her 1996 article, Gender as a Social Category in Native Southern New England, in Ethnohistory 43 (4).

[3] Champlain’s description of women’s work is in the Otis translation of the Voyages of Samuel de Champlain for the year 1615, edited by Slafler, in Gutenberg.org (this work lacks pagination). Roger Williams remarks on male and female roles in producing food in A Key into the Language of America, p. 37.

[4] Champlain, p. 86, in Volume 2 of the Prince Society edition (1878), a free ebook in Google.

[5] Champlain’s account and drawing of deer hunting are in Volume II of Voyages (Otis 1878: http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-115/summary).

[6] See William Bradford,’s description of the driving yard in Of Plymouth Plantation—1620-1647, William T. Davis. ed. (1908): http://mith.umd.edu//eada/html/display.php?docs=bradford_history.xml. Interestingly, in November 1620 William Bradford inadvertently stepped into a deer spring trap and was hoisted into the air by his feet, much to the amusement of his companions as well as Massasoit’s huntsmen.

[7] For anthropological perspectives on characteristics of hunting and gathering societies, see the discussion and references on the Human Relations Area Files web site at http://hraf.yale.edu/resources/faculty/explaining-human-culture/hunter-gatherers-foragers-2/.

The site presents new research and questions on the topics of gender inequality, social stratification, and violence in hunting and gathering societies compared to agrarian societies. Classic accounts of plant and animal species present in the estuaries of the Northeast appear in Champlain’s accounts and John Smith’s A Description of New England (1616), Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s Relation (1622); William Wood’s New England’s Prospect (1634); Thomas Lechford’s Plain Dealing (1642); Edward Johnson’s Wonder-Working Providence (1654); Ferdinando Gorges’ America Painted to the Life (1659); Samuel Maverick’s A Briefe Description of New England (1660); and John Josselyn’s New England’s Rarities Discovered in birds, beasts, fishes, serpents, and plants of that country (1674).

[8] To harvest wild rice, women bent over the stalks onto the gunwales of their canoe and threshed the rice with paddles so that the grains fell onto mats on the floor of the canoe. They then released the stalks, which could continue to produce, and bundled the grains for storage or further processing. The illustration of Ojibwa women harvesting wild rice in the 19th century is in the public domain, by S. Eastmen, in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (1853).

[9] Sources for these lists include relevant foraging series and field guides, e.g., Foraging New England; Native Edible Plants in New England; Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer; Frank G. Speck (1917): Medicine Practices of the Northeastern Algonquians, in Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Congress of Americanists: 307-313; Ralph W. Dexter and Frank G. Speck (1950), Utilization of Animals and Plants by the Micmac and Malecite Indians of New Brunswick, Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 38(8): 257-265 and 41(8): 25-259; John Josselyn (1674): New England’s Rarities Discovered in birds, beasts, fishes, serpents, and plants of that country, W. Veazie, Boston: http://www.archive.org/details/newenglandsrarit00joss; Marie Svoboda (1967): Plants that the American Indians used, Museum Stories 341-349. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. See also my slide lecture on Algonquian Foodways and Medicinal Plants (Gloucester Lyceum and Sawyer Free Library, Gloucester MA, 2020): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ir_RApGuJjU.

For a comprehensive list of plant species in Gloucester in the 1950s, see Elliott C. Rogers, Botanist’s Eye View of Dogtown Flora, Gloucester Daily Times (August 27, 1954). See also Eleanor Pope’s The Wilds of Cape Ann (1981). For local gathering, see Brandeis University’s web site, Taste of the Wild: A Guide to Edible Plants and Fungi of New England, at http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/fieldbio/Edible_Plants_Ramer_Silver_Weizmann/Pages/Homepage.html and the sources it cites at http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/fieldbio/Edible_Plants_Ramer_Silver_Weizmann/Pages/references.html. See also the Foraging Guides for New England or the Northeast published by Falcon Guides, for example Tom Seymour’s Foraging New England: Edible Wild Food and Medicinal Plants from Maine to the Adirondacks to Long Island (2013).

[10] Francis Higginson (1629), New England’s Plantation: A Short and True Description of the Commodities and Discommodities of that Country, reproduced without pagination at http://www.winthropsociety.com/doc_higgin.php.

[11] In this 1585 drawing, the Virginia Algonquians in the dugout have a dip net, while the women in the center are poised to throw a cast net. Others in the background are spearing fish at weirs. In the foreground the artist drew in the water (left to right) a ray, sea turtle, crab, sturgeon, two horseshoe crabs, and a mackerel. The foreground features shellfish, edible seaweed, beach pea, the wood lily with its nutritious bulb, and other edible plants [12].

[12] John Josselyn’s quote is on p. 99 of his An Account of Two Voyages to New-England Made during the years 1638, 1663 (1674): http://archive.org/details/accountoftwovoya00joss.

[13] Champlain Voyages (1605), p. 75. It was Thomas Morton who noted in New English Canaan (1637) the practice of making trail kit containers or canteens out of sewn horseshoe crab shells. Horseshoe Crabs are not crabs but arthropods related to spiders and scorpions; they are protected in New England today and may not be taken. In Essex County, from their nursery area in Plum Island Sound they still come ashore to breed on a few Cape Ann beaches—for example, at Old Garden Beach in Rockport—at high tide on the first nights of the new moon and the full moon in May and June. None seen today are so large as the ones Champlain described, some two feet across.

[14] “The Broiling of Their Fish Over the Flame” is a John White watercolor from 1585 in Virginia. The fish on stakes are being smoked and dried.

[15] See my article, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Spring 2017. 78 (1): 28-40. Algonquian Shellfish Industries on Cape Ann, at https://vc.bridgew.edu/do/search/?q=&start=0&context=12398681&facet=at).

[16] For an overview on corn hills, see De la Barre and Wilder (1920) Indian Corn-Hills in Massachusetts, in the American Anthropologist.

[17] See aso my 2017 article, Speck in Riverview, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (2): 60-70.

[18] For a general perspective on the archaeological significance of shell heaps, see Jordan Kerber (1985), Digging for clams: Shell midden analysis in New England, in North American Archaeologist 6 (2).

[19] Any online college or university site will explain Darwin’s theory of natural selection and related concepts for understanding biological evolution. One of the best explanations of natural selection I’ve seen is Palomar’s tutorial at http://anthro.palomar.edu/evolve/evolve_2.htm. Charles Darwin’s explanation of the adaptive radiation of varieties of a species is in his 1845 Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. 2d edition. 1. For perspectives on the actual process of plant domestication, see Virginia Betz’s article (1996-2002), Early plant domestication in Mesoamerica (Athena Review 2), at http://www.athenapub.com/nwdom1.htm.

[20] For Indigenous sources on horticulture see “Three Sisters Gardening” at https://www.nativeseeds.org/blogs/blog-news/how-to-grow-a-three-sisters-garden; Caduto and Bruchac (1996) Native American Gardening; Kavasch (2005): Native Harvests: American Indian Wild Foods and Recipes; and Sherman (2017): The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen.

[21] Even before the domestication of maize indigenous people were cultivating seed-bearing and edible leaf plants such as marsh elder and the chenopodiums. Chenopodiums include amaranth and goosefoot, also called lambs’ quarters, which have edible leaves and produce a grain similar to Quinoa. Dried seeds of marsh elder, goosefoot, and amaranth were often ground together as flour to use as a thickener and in baking. Amaranth also had medicinal uses. It is high in vitamin C and infusions of the leaves and flowers were used to treat various ailments. They also added dried amaranth leaves to their tobacco mixtures, along with with dried sumac leaves, shaved chokecherry bark, sunflower leaves, and native nicotiana

[22] Descriptions of trees and shrubs cultivated and used by Eastern Woodland Indians for diverse purposes are given in Champlain’s Voyages (Chapter 13, September 1603), Morton (pp. 40-46), Josselyn (pp. 110-112), and other sources. Aside from Champlain’s accounts, Thomas Morton’s description of Algonquian forestry practices (pp. 36-37) is the earliest of several English sources. Native American land use in New England is beautifully explained in William Cronon and John Demos, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (2003 rev. ed.). For insight into recognizing Native American and colonial impacts on the land today, see Tom Wessels’ book, Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England (1997).

[23] Observations made by these and other “discoverers” are reported in my forthoming paper, “Burning the Woods: What’s the Real Story?”

[25] Please see the extensive bibliography in my “Burning the Woods” paper. Many sources support these claims.

[26] My principal sources for Algonquian agriculture are Bruce Smith’s 1989 article, Origins of agriculture in eastern North America, in Science 246: 1566-1571, and Christopher Doughty’s 2010 article, The development of agriculture in the Americas: An ecological perspective, in Ecosphere 1: 21. The origin of maize as a single domestication event in the Balsas River Valley of Mexico, rather than having independent inventions in different areas, has been proven through genome studies. See Yoshihiro et al., A single domestication for maize shown by multilocus microsatellite genotyping, at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC122905/. The new studies confirm archaeological evidence, with the oldest known fossil maize in Oaxaca, and put to rest the proposal that corn was domesticated independently in the Mississippi Valley. Interestingly, the wild plant that originally became Indian corn grew on dry plateaus and not in the humid continental latitudes of today’s cornbelt.

[27] Maiz is Spanish for corn, from mahiz, its Arawak name. In Mesoamerica in the 15th century, the Conquistadores found indigenous peoples practicing ingenious solutions to the challenge of maximizing maize production in dry environments at high, steep elevations, such as terracing hillsides and building floating gardens as artificial islands in lakes. The Aztec method of floating gardens, called chinampa, is still practiced. For more detailed information on Aztec farming, see Chinampas: The Floating Gardens of Mexico on Ancient Origins: http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-americas/chinampas-floating-gardens-mexico-001537

[28] For an appreciation of the significance of environmental factors in food production, see Jared Diamond’s article, Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication in Nature 418: 700-7007 (August 8, 2002). A wonderful indigenous source for understanding Indigenous concepts of the interconnectedness of people with plants and animals and with the earth is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass.

[29] For a review of theories about the domestication of maize, see Tracking footprints of maize domestication and evidence for a massive selective sweep on chromosome 10, by Feng, Stevens, and Buckler (2009) at http://www.pnas.org/content/106/Supplement_1/9979. See also David Braun’s post on the National Geographic web site (2009), Corn domesticated from Mexican wild grass 8,700 years ago, at http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/2009/03/23/corn_domesticated_8700_years_ago/.

[30] For a good summary of evidence for the introduction of the cultivation of corn to New England, see Bruce Smith’s Origins of agriculture in eastern North America in Science 246 (1989) and the articles in Hart and Reith’s Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change A.D. 700-1300 (2002) at http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/staffpubs/docs/14644.pdf. See also S. Johannessen and Christine Ann Hastorf (1994), Corn and culture in the prehistoric New World.

[31] That the Middle and Late Woodland people brought agriculture to New England from the west and southwest (meaning from the Mississippi, Ohio, and Susquehanna river valleys) is also supported by archaeological evidence in Pennsylvania and New York. See, for example, William Ritchie’s A Typology and Nomenclature for New York Projectile Points (1970) http://www.librarything.com/work/8440840 and the Ritchie and Funk book Aboriginal settlement patterns in the Northeast (1973). For additional ethnographic evidence for diffusion, see S. Johannessen and Christine Ann Hastorf (1994), Corn and culture in the prehistoric New World. The theory of cultural diffusion was developed by anthropologists during the mid-20th century. See, for example, Alfred Kroeber’s 1940 article, Stimulus diffusion, in American Anthropologist 42 (1). The related idea that ideas can spread from one community or society to another independently of human migration is also found in the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins’ concept of memes—ideas that act as transmissible objects without specific human agency, from The Selfish Gene (1976). The Algonquians’ legend explaining how they acquired agriculture is an example of the transmission of culture through memes. Roger Williams first recorded the Algonquian legend of the crows bringing corn and beans to New England in A Key to the Language of America (1643), p. 144.

[32] It bears repeating that agriculture was a global phenomenon wherever it was environmentally supported, because we often have mistaken beliefs about the origins of cultural achievements and the presumed superiority of the people achieving them. Though it seems counterintuitive to say so, particular societies do not always figure prominently in the human story. Humans are everywhere equally smart and inventive and always have been. For better or worse we all have always done the best we could with whatever we had, wherever we found ourselves.

[33] Sources for agriculture in New England include Howard Russell (1980) Indian New England before the Mayflower and Elizabeth Chilton, Tonya Largy, and Kathryn Curran (2000), Evidence for prehistoric maize horticulture at the Pine Hill site in Deerfield, Massachusetts, in Northeast Anthropology 59. See especially Chilton’s 2006 article, Pre-Contact Maize Horticulture in New England: A Summary of the Archaeological Evidence, in A Memorial Volume in Tribute to Elizabeth Alden Little (1926-2003). Mary Lynne Rainey, ed.

[34] Champlain’s account of agriculture on the Gulf of Maine below the 44th parallel is in Chapter VII of Volume 2 (1604-1610) of Voyages of Samuel de Champlain (the Otis translation, edited by Rev. Slafler). See also Champlain, p. 86, in Volume 2 of the Prince Society edition (1878), and Marshall Saville, Champlain and His Landings at Cape Ann, 1605, 1606 (1934).

[35] In this illustration from the 1580s of planting corn in Virginia, Algonquian men are clearing fields and women are planting mouth-moistened seeds by blowing them into prepared rows of holes. Theodore DeBry’s engraving is in his A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590). Compare with the DeBry Collection of “Great and Small Voyages” in Terra Incognita. Early Accounts at http://library.wustl.edu/units/spec/exhibits/terra/index.html.

[36] Corn-planting mounds are reported by Edmund De la Barre and Harris H. Wilder in Indian Corn-Hills in Massachusetts, American Anthropologist, New Series 22 (1920) and in Daniel Boudillion’s 2009 discussion of corn planting mounds in Nashoba Hill: The Hill that Roars (field investigation): http://www.boudillion.com/nashobahill/nashobahill.htm. In 1940, N. Carleton Phillips reported finding preserved corn-planting mounds in a drained swamp behind Coffin’s Beach, now buried in sand dunes and scrub. Pre-Contact agriculture on Cape Ann is attested in both archaeological and anecdotal evidence. See, for example, Lepionka (2013), N. Carleton Phillips (1940), and Ebenezer Pool (1823).

[37] In addition to the standard accounts of explorers and settlers, my principal source for Algonquian crop domestication is M. K. Bennett (1955), The food economy of the New England Indians, 1605-1675, in the Journal of Political Economy 63 (5).For a good summary of evidence for the introduction of the cultivation of corn to New England, see Bruce Smith’s Origins of agriculture in eastern North America in Science 246 (1989) and the articles in Hart and Reith’s Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change A.D. 700-1300 (2002) at http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/staffpubs/docs/14644.pdf.

[38] The remnant field of corn hills is at Nashobah, a “Praying Indian” Town in the 17th century. The photo of a three sisters garden is from https://www.thesurvivalgardener.com/three-sisters-garden-updates/ (with permission). The illustration is from Creative Commons.

[39] An entheogen is a mind-altering or hallucinogenic substance. Native Americans used entheogens such as tobacco to heighten spiritual experience in prayer, meditation, and the vision quest.

[40] The illustration of a Native man smoking Virginia tobacco was an ad for the Lorillard Tobacco Company, founded in 1760 in Virginia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorillard_Tobacco_Company). He is leaning on a hogshead, a wooden barrel, 48 inches (1,219mm) long and 30 inches (762mm) in diameter, used in colonial times to transport and store tobacco. Fully packed with tobacco, it weighed about 1,000 pounds (500 kg).

[41] Jacques Cartier reported on the Native North American use of tobacco on p. 276 of Volume III in the 1810 edition of his Two Voyages (1535). Christopher Columbus and his party were the first to witness the practice, which included the inhalation of tobacco powder through the nostrils using a straw. See the National Park Service article on the discovery and history of tobacco at http://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/tobacco-the-early-history-of-a-new-world-crop.htm.

[42] For more information on the role of corn and tobacco in trade during the Contact Period, see At the Water’s Edge: Trading in the Sixteenth Century in James Axtell’s After Columbus (1988) and Kenneth Andrews’ Trade, Plunder, and Settlement: 1480–1630 (1984). For a perspective on the impacts of the tobacco trade on Native American and colonial cultures in the Northeast, see Fred Anderson and Andrew Clayton, Champlain’s Legacy: The Transformation of Seventeenth-Century North America, in The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America, 1500-2000.

[43] For additional information on dry farming see Cresswell and Martin, Dryland farming: Crops and techniques for arid regions (1998): http://people.umass.edu/psoil370/Syllabus-files/Dryland_Farming__Crops_&_Tech_for_Arid_Regions.pdf (ECHO Community).

[44] See, for example, David Johnson’s (2020) Native Americans’ Sacred and Ceremonial Landscapes Correlation with Groundwater, Hudson House Publishing, Poughkeepsie, NY.

[45] In this artist representation, Algonquian women and children are harvesting green corn for their mid-summer green corn festival celebration. Gourds are left to harden into water containers under the cornstalks. The boy on the scaffold is doing his stint as a scarecrow. He has a small arsenal of stones up there to throw at the crows. Children, youths, and adults all took turns manning temporary shaded platforms to watch over the corn crop and scare away the crows.

[46] Francis Hutchinson, William Wood, William Bradford, and others remarked on the colonists’ use of fish as fertilizer in their cornfields. See Hutchins (2014), p. 44. However, there is scant archaeological evidence for its regular use in Native cornhills. See, for example, Robert Hasenstab’s article, Fishing, Farming, and Finding the Village Sites, in The Archaeological Northeast (1999) and Lynn Ceci’s article in Science, Fish Fertilizer: A Native North American Practice? (1974).

[47] Colonial bounties on wolves and later crows are attested in the laws of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. See the Book of the General Laws of the Inhabitants of the Jurisdiction of New-Plimoth, and Generall Laws of the Massachusetts Colony, revised and published, by the Order of the General Court (1632-1676) http://www.princelaws.pdf (also at http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/tlc0200.jpg. See also pp. 16, 32, 37, 39, and 52 in Mary Ray, (Sarah Dunlap, Ed.), Gloucester Massachusetts Historical Time-Line ~1000—1999 (Gloucester Archives, 2002).

[48] William Bradford gives Squanto’s story and describes the first colonial planting at Plymouth on pages 115-121 in his History of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647 (in the 1898 edition on Guterberg.org).

[49] The colonists used potash to make lye, soap, and gunpowder. Carolyn Merchant points out that potash and charcoal were the first forestry exports from northern New England as a consequence of the use of fire to clear land for cultivation. See Ecological Revolutions (2013), pp. 191-192.

[50] For more information on swidden agriculture and forest management in New England, see Christopher Hannon’s Indian Land in Seventeenth Century Massachusetts in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts (2001) at http://www.wsc.mass.edu/mhj/pdfs/Hannan%20Summer%202001%20complete.pdf. Indigenous use of fire to clear land for farming usually was not destructive, as one might assume. Fires are natural disturbances of forest ecosystems. Slash and burn agriculture is an ancient and worldwide method of clearing land. It creates open forest and parkland environments, free of underbrush, making movement, hunting, gathering, and defense easier and safer. Burning is destructive only when forests are “clear-cut” on a large scale. Large-scale clear-cutting of rainforests for logging, mining, or commercial agriculture is a factor in global warming. Removal of vegetation eliminates a means of CO2 absorption, which increases the greenhouse effect, and causes surface erosion, which damages thin forest soils and contaminates waterways. Environmental impacts of clear cutting are variable, complex, and controversial. Forestry scientists point out how clear cutting and burning in moderation actually improve the land, while environmental scientists point out how these methods can destroy ecosystems on a scale massive enough to affect the planet. A reasonably balanced explanation is given by Alina Bradford on Live Science (March 4, 2015) at http://www.livescience.com/27692-deforestation.html.

[51] Champlain’s observation of slash and burn planting in Essex County is on p. 115 of the Prince Society edition of Voyages (1878) and is widely reprinted, for example, in George Dow’s Two Centuries of Travel in Essex County Massachusetts (1921), and in Duane Hurd’s History of Essex County (1888).

[52] Elizabeth Chilton (2010) explores the concept of mobile farming in Mobile farmers and sedentary models: Horticulture and cultural transitions in Late Woodland and contact period New England, in Susan Alt, ed., Ancient Complexities: New Perspectives in Precolumbian North America (2010): 96-103.

[53] All the early observers remarked on the practice of controlled burning. See, for example, Thomas Morton, New English Canaan, Book One, pp. 36-37. My principal secondary sources on Native American and colonial farming in New England are William Cronon and John Demos, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (2003 Revised edition); David Arnold, The Problem of Nature: Environment, Culture, and European Expansion (1996); and Howard Russell, A long, deep furrow: Three centuries of farming in New England (1976).

[54] For more details on traditional Indigenous uses of corn, see the article on maize at http://www.sacredearth.com/ethnobotany/plantprofiles/corn.php. For example, this article explains the use of lye and fermentation in the preservation of corn. The significance of corn in Native American life is reflected in its role in the origin stories of many tribes and nations, such as the Corn Mother in diverse Algonquian legends, in which the first woman, with her husband’s help, sacrifices herself to feed their children with sacred corn that springs form her body.

[55] William Bradford’s party at Plymouth survived their first year by raiding Pokanoket storage pits for food. Bradford describes the discovery and scavenging of Indigenous food stores at Plymouth on pp. 99-100 of his History of Plymouth.

[56] Roger Williams, A Key into the Language of America, pp. 11-12. Others also remarked on samp, parched corn (nokehick), and other corn preparations, for example William Wood in New England’s Prospect, p. 76. Samp Porridge Hill in Annisquam, Gloucester, is on the list of Archaic Community, District, Neighborhood Section and Village Names in Massachusetts, published by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Citizen Information Service: http://www.sec.state.ma.us/cis/cisuno/unoidx.htm.

[57] John Josselyn describes clambakes in An Account of Two Voyages, p. 109. Se also Francis Baylies, A Historical Memoir of the Colony of New Plymouth (1830). William Bradford describes the discovery and scavenging of Indian food stores at Plymouth on pp. 99-100 of his History of Plymouth.

[58] According to William Bradford (p. 201), by 1623 Indian corn had become a medium of exchange “more precious than silver.” The use of corn as currency is evident in the Book of Indian Records for Their Lands (Massachusetts General Court, 1861).

[59] In White’s 1590 drawing, an Algonquian couple in Maryland is sharing a plate of beans. We also see a gourd of drinking water, a tuber or root, walnuts, a fish, corn on the cob, and a clamshell, emblematic of their diet. The man also has his clay pipe. White’s paintings and De Bry’s engravings of them depict Native Americans of Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, and the Carolinas as muscular, robust, and uninhibited in movement but also oddly European-looking in facial features and body proportions. This might be explained as a confirmation bias in the “eye of a beholder” or distortion introduced by copy artists and other engravers who never saw Native Americans first hand. Stylistic changes in the depiction and iconography of Native Americans are a fascinating subject. See, for example, Christian Feest, The Virginia Indian in Pictures 1612-1624 in The Smithsonian Journal of History 2 (1) (1967).

[60] A pit in the sand was lined with fire-heated rocks with a layer of damp seaweed on top (1). Then a layer of clams or other bivalves (2), then a layer of chopped vegetables (3), then a layer of thin-sliced meat (4), then a layer of lobsters and crabs (5), then a layer of green corn (6), and then another layer of damp seaweed on top (7), all covered over and sealed in with woven mats secured with rocks, creating essentially a baking pit.

[61] Thomas Morton wrote about the preservation and storage of corn in New English Canaan, Book One, pp. 29-31, and Book Two, pp. 57-60. See also Howard Russell, How aboriginal planters stored food, in Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 23 (1962).