It seems a simple enough question: What other Europeans came here prior to settlement and what did they discover? Other than Champlain, I expected to confirm the landfalls of Columbus in the Caribbean, Ponce de Leon in Florida, Cartier in Newfoundland, Cabot in the Maritimes, Hudson in New York, and Smith in New England before getting to Bradford in Plymouth and the Dorchester Company, but instead I found a whole roster of complete unknowns (to me)—those who never made the history textbooks for undergraduates back in the day. For history is nothing if not selective. Those who may have seen the Algonquians of New England, Essex County, and Cape Ann prior to settlement included fleets of fishermen, fur traders, and slavers along with empire builders and those seeking gold, passages to the Orient, and eternal youth.

It’s perhaps easier to start with who did not come to Cape Ann, and that would include the Vikings. I found no evidence, not even a shred of circumstantial evidence, that Leif Ericson’s brother Thorvald was buried on Cape Ann in 1004 AD or even that Vikings actually set foot here. The surname actually was Eirikssen, and the father of Leif, Thorvald, and Thorstein Eirikssen was Erik Thorvaldson, or Erik the Red, the developer, if not discoverer, of Greenland.1

The Viking Question

Robert Pringle, citing the 11th century Icelandic sagas in his 1895 history of Gloucester, says the Vikings named New England Vinland in 1007, but candidates for that name range from L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland to sites in New Brunswick; Newport, Rhode Island; Martha’s Vineyard; as far south as Virginia; and as far west as Minnesota. In Old Norse, vinland apparently could have meant “pastureland” or “meadowland” or “land of grapes” depending on how the word was pronounced. Those features of terrain would have been characteristic of New England, but hardly diagnostic of Norse exploration on Cape Ann. Algonquians created meadowland or parkland all along the Atlantic seaboard through their methods of land use, and wild grapevines grew on trees all up and down the coast between Newfoundland and New Jersey. The Sagas, meanwhile, refer to a heavily forested cape, not a parkland with vines, facing an elbow-shaped north-facing cape to its south, which Pringle and others took to mean Cape Cod.2

Confirmed Viking site at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland

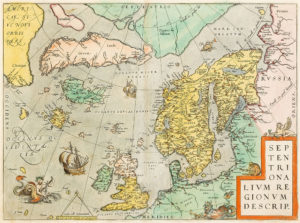

Surviving Viking maps of the North Atlantic rim extend no further south than 50 degrees north latitude, supporting the conclusion that the lands and peoples the Norse described may have included Algonquians but were all north of Cape Ann, which lies below the 43rd parallel. Even assuming the explorers sailed farther south than their maps record, the problem remains of a lack of accepted or substantiated physical or documentary evidence.3

Ancient Viking Map of the North Atlantic Rim

Ortelius’s Map of the Scandinavian World in 1573

According to the Icelandic sagas and the 15th century Skalholtsbok manuscript, Thorwald—fatally wounded by natives he had attacked—requested to be buried at Krossanes, “Cape of the Crosses”, a mistranslation of Krossarnes, “Crossness”. This burial site has been claimed by Hampton, NH (which has a rock with rune-like scratchings claimed to be Thorvald’s headstone); as well as by Cape Neddick, ME; Gloucester, MA; Boston; Nahant; Lynn; and Duxbury. Duxbury even named a promontory Krossanes, quoting the same words other towns use to justify their claims. Other supposed runestones in New England, such as Dighton Rock in Berkeley, MA on the Taunton River, have not been authenticated despite perennial speculation. In Massachusetts, artifacts or sites of proposed but disputed Norse origin have also been found in Cambridge, Hingham, Medford, and a number of spots on Cape Cod.4

Thorvald’s Alleged Gravestone in Hampton, NH

Dighton Rock in an 1853 Daguerreotype

In 1874 an influential book by Rasmus Anderson broke the news that the Norse and not Columbus had discovered America. Anti-Catholic and nativist Scandinavian groups promoted the claim, and soon there were new Viking archaeological finds from Wisconsin to Boston, where E. N. Horsford “discovered” that Norembega was really a Viking settlement on the Charles River. Victorian enthusiasm for the newfound historical significance of the Vikings was honored in the Columbian Exposition (or Chicago World’s Fair) of 1893, where a replica of a Viking ship was displayed along with replicas of the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria.5

The Viking en Route the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair

The exhibit of this replica of Leif Erikson’s Viking ship created a sensation at the Columbian Exposition and sparked a flurry of local efforts to “correct” their historical records. Historians of Cape Ann in the 1890s were not immune to the excitement. At that time, for the first time, the Vikings were added to local history. (James Robert Pringle, a journalist, publicist, and amateur historian living in Gloucester at the time, likely was influenced by the Viking craze.)

A postage stamp issued in the U.S. in 1925 commemorates the Viking ship featured in the Columbian Exposition. In 1919, the Scandinavian Fraternity of America petitioned Congress to declare officially that Leif Erikson discovered North America. Ultimately, in 1964, October 9 became Leif Erikson Day as an optional holiday and alternative to Columbus Day on the national calendar. A Leif Erikson postage stamp was issued in 1968. Appropriation of the Vikings as a cultural icon includes statues and sports teams in communities as near as Rockport, MA and as far away as New Zealand with historically high populations of Scandinavian immigrants.6

Viking Stamps

In his 1892 self-published History of Gloucester and Cape Ann, Pringle wrote that Thorwald was buried in Gloucester somewhere along the Back Shore. Earlier historians Adams, Babson, and Thornton had somehow failed to mention this. Norse literature states that Thorwald, sailing south in 1004 AD, had been going east around a rocky north-facing cape when he put ashore to mend a damaged rudder, found six Skraelings [natives] hiding under their beached canoes, killed them, except for one escapee, and was soon after mortally wounded in a retaliatory attack. It is written that he requested to be taken to a preferred spot to be buried and that the place be called Krossanes. According to Pringle, Krossanes was at Bass Rocks. There was even a Hotel Thorwald at Bass Rocks between 1899 and 1965, when it burned down. In 1909 it had 175 Rooms for Summer Tourists at $17.50 to $35 a Week.7

Hotel Thorwald (on the left) in 1909

Norse literature also states that Thorvald’s burial site lay between two fjords, evidence of which neither Bass Rocks nor Cape Ann in general can provide. Pringle’s claim that Krossanes was on Cape Ann nevertheless persists as a part of our official history. A Krossarnes does exist as a village in Iceland, Thorvald’s original homeland. Vikings are said to have gone to great lengths to have their bodies buried at home in Christian consecrated ground. Wherever in Vinland Thorvald was buried, his brother Thorstein later attempted unsuccessfully to retrieve the body in a subsequent expedition, most likely to rebury him in consecrated ground in Iceland.8

That so many different towns wanted to be the home of the Vikings in America testifies to the enormous romance and caché the 19th century imagination attached to the drama of discovery. That was also the time when, in another great feat of imagination, a particular boulder on the beach became immortalized as Plymouth Rock. The boulder apparently had been identified in 1741, a hundred and twenty-one years after the Mayflower landing, by a 92-year-old church elder whose father had pointed it out to him on the beach (and who had not wanted a wharf to be built there).9

Plymouth Rock in the Victorian era (Hammett Billings, 1867)

But so much for who did not come to Cape Ann. Other than the Vikings at Vinland a thousand years ago, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, Breton, Dutch, and French explorations and settlements all predated the English by as much as a hundred years. Among the many explorers who visited New England shores prior to the first attempted settlements were, as expected, Giovanni Caboto (known as John Cabot) and his sons, starting in 1497, and John Smith, starting in a 1607 sail-by on his way to Virginia, less than a year after Champlain had come ashore in Gloucester Harbor. Most history texts fail to mention other early discoveries, however, such as the Portuguese Diogo Ribeiro’s 1529 sightings of the White Mountains of New Hampshire, which have seven peaks above 5,000 feet and can be seen far out to sea.10

Textual and archaeological evidence shows that as early as the late 14th century Basque and Breton fleets fished the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, Georges Bank in the Gulf of Maine and Tillies Bank, Jeffrey’s Ledge, and Stellwagen Bank off the Massachusetts coast. Later English chroniclers, such as John Brereton, on a 1602 Sir Walter Raleigh-sponsored voyage with Bartholomew Gosnold and Bartholomew Gilbert, reported how they saw “Indians” rowing Basque barques and wearing Basque jackets, caps, and leggings. Martin Pring, sailing up the Penobscot River in 1603, also saw evidence of Basque contact. In 1604, Champlain encountered Basques fishing near Sable Island off Nova Scotia who told him that Basques had been fishing there for more than a hundred and fifty years.11

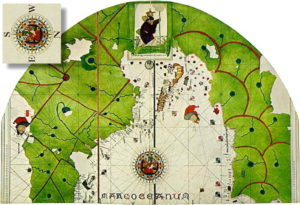

Cosa’s Basque World Map of 1505 with Sites in North America

Basque seasonal fishing stations were clustered along the coast of Labrador, such as at Red Bay, and at sites such as Port aux Basques and St. Anthony in Newfoundland. Newfoundland was the Antarctica of the 16th century (until 1583 when Humphrey Gilbert claimed it for Queen Elizabeth and England). Different European nations claimed different portions of the coastline to establish fishing stations and processing centers for their fishing fleets. In this way countries shared the great bounty of codfish and whales, driving bowhead and right whales to near extinction within a hundred years.12

The Basques exported fish and whale oil to Europe and imported glass beads to trade with the Inuit. The Bretons (from Brittany, geographically the French equivalent of England’s Cornwall) fished off Nova Scotia and in the Gulf of Maine and claimed to have explored the entire coast of North America prior to Spanish claims to Florida in 1513. Indigenous Peoples living on the coasts, the first to become acculturated and bilingual in contact situations, became important middlemen in the European trade.13

Breton Fishing Stations on the Coast of Nova Scotia and Maine