The Algonquians were matter-of-fact, even sanguine, about matters of life and death—and as red in tooth and claw, so to speak, as their prey and their human enemies. Nevertheless, their burials and totems and other practices attest to their beliefs in a positive afterlife and a vast spirit world overseen by higher powers, one of which was called by many Gitchi Manitou or Great Spirit. People, animals, rocks, spirits, and everything in nature were endowed with innate manna-like spiritual power (manitou, or manitôk or manidoo). That power could increase or decrease, be transferred, cause physical transformations, and work magically for good or bad. These beliefs shaped people’s body images and identities, their relationships with each other, and their behavior toward others, nature, and the land. I think these beliefs are the whole reason behind the incredible mismatch between them and the Europeans, equally driven by their beliefs. Thus, I lay their ultimate mutual failure in cultural contact at the feet of religion (if such a metaphor can be entertained), and some other historians would agree. The earliest Indian wars against European missionaries and settlers were as much attacks on Christianity as efforts to reclaim territory [1].

The Algonquian Cosmos

Algonquians believed in a three-part intersecting universe, with an upperworld (skyworld), earth (Turtle Island), and a lowerworld (waterworld). According to various ethnological and ethnohistorical accounts, god-like beings, demi-gods, ancestors, demons, spirits, giants, and elf- or troll-like creatures called Little People inhabited these worlds along with (or in) the people, plants, animals, landforms, stars, and natural phenomena. In addition to having manitou, everything identified as “animate” was anthropomorphized, and this included trees and rocks. Talking to the wind, reading animal encounters as omens, acting on dreams, hiding from meteor showers, seeking transformation through spirit possession, and leaving offerings at cracks in bedrock would all have been completely normal. The universe was alive in every way, and it was always possible that you couldn’t believe your eyes–that nothing was what it seemed. Algonquians lived magic realism in real time, time that continually curved and recurved in coils and circles, for Native Americans lived in a nonlinear multiverse. Europeans’ superstitions were no match, and Europeans ultimately lived in a post-Enlightenment empirical world of cause and effect—a linear world of beginnings, middles, and ends—a world where things were expected to be rational, and where monotheism and religious dogma had the power to simplify everything—a world that could be divided, commodified, and owned in perpetuity [2].

Algonquians did not at first grasp the idea that land and resources could be commodified and exchanged, any more than we at first understood how cubic feet of air over highways could be bought and sold for commercial development. Land and resources belong to Earth, which belongs to everyone. Early Indian deeds to farmsteads were understood as usufruct–with rights of usage during the settler’s life, but later deeds contain carefully worded riders preserving essential resource procurement areas for Indigenous use, such as “Roger’s Brook” and “Will’s Hill”.

Manitou

Algonquians believed that supernatural beings and forces governed every aspect of the natural world. The sun, moon, stars, thunder, rain, springs, trees, rocks, plants, animals—other things, conditions, and events designated as “alive”—all had both consciousness, the ability to communicate to people, and spiritual power–manitou. Shamans invoked and channeled or repelled this manitou as needed as they mediated between people and the spirit world.

Anthropologists call this belief in a spirit world animism and in nature’s consciousness as animatism. Algonquian spiritualism included belief in all forms of magic and the practice of sorcery or witchcraft. The shaman’s ritual paraphernalia used in sorcery–which included quartz crystals, polished gemstones, the bones of small animals, tobacco, and other mind-altering substances–were carried in a “medicine bag” and kept secret. The celebrated Native American culture of respect for all things can be seen as essentially born of fear and uncertainty in the face of a multi-faceted, all-powerful, and unpredictable supernatural world [3].

A Small Sample of Algonquian Spirits [4]

| Algonquian Name | English Translation |

| Kautantowit; Cautantowwit

(also Keihtanit, Keihtan) |

Great Spirit, place of Great Spirit (Giver of corn, squash, and beans) |

| Manit, Manitou (Manitoo); Manittoowock; Manitoog (plural) | Spirit; Spirits, gods |

| Nammanittoom | My Spirit |

| Nuttauquand | Spirit of My People |

| Keesuckquand | Sun Spirit |

| Kesuckanit | God of Day |

| Nanepaushat | Moon Spirit |

| Chekesuwand | West Spirit |

| Womopanand | East Spirit |

| Wunnanameanit | North Spirit |

| Sowwanand | South Spirit |

| Squauanit | Woman’s Spirit |

| Muckquachuckquand | Children’s Spirit |

| Paumpagussit | Sea Spirit |

| Abbomocho (Hobbomock, Chepi) | Healing Spirit; Death Spirit |

| Yotaanit | Fire Spirit |

| Nashauanit | Spirit of the Creator |

| Woonand (Wunnand; Woonanit) | Spirit of Goodness |

| Mattand (Mattanit | Spirit of Evil |

| Nisquanem | Spirit of Mercy |

| Mosquand | Bear Spirit |

| Psukand | Bird Spirit |

| Tunnuppaquand | Turtle Spirit |

| Nimbauwand | Thunder Spirit |

| Hussunnand | Stone Spirit |

| Askuquand | Snake Spirit |

| Seipanit | River Spirit |

| Cowawand | Pine Tree Spirit |

| Ohomousanit | Owl Spirit |

| Moosanit | Moose Spirit |

| Quequananit | Earthquake Spirit |

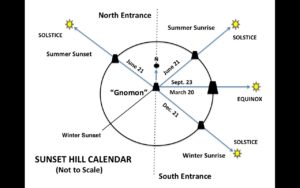

Shamans also were involved in keeping time for the Algonquian ceremonial calendar, and remains of these calendars may still be seen in boulder fields in New England landscapes. These ceremonial landscapes reflect the solar, lunar, and astral cycles by which people tracked ceremonial time. They are manipulated landscapes in which boulders and false horizons mark observation posts, sightlines, and alignments to skyworld events. There is a native solar observatory on Pole Hill in Riverview, Gloucester, for example, with reference rocks and sightlines for the summer solstice sunrise and sunset, the winter solstice sunrise and sunset, the spring and fall equinoxes, and other astronomical events, such as the traverse of Ursa major through the winter night sky. The observatory was first built by Late Archaics or Early Woodland peoples around 3 thousand years ago, and further modified by later peoples, with the sighting stones organized around a central reference point on the north-south aligned axis. The cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) were central concepts in Algonquian cosmology, practice of medicine, village planning, burial practices, and use of divination [5].

Pole Hill Solar Observatory and Calendar

As in ancient Southwestern, Mexican, Mesoamerican and South American societies, observed movements of the sun, moon, and stars in their skyworld cycles guided the spiritual life of the community. In New England, for example, when the Milky Way touches the horizon the spirits of the deceased can find their way to the skyworld on the starry path under a nearby constellation’s protection from underworld spirits. Astronomical observations also guided the community’s seasonal activities, such as the bear sacrifice in winter, the New Year’s celebration in spring, thanksgiving for the first harvest of green corn in mid-summer, and celebration of the last harvest before fall’s first frost [6].

Milky Way Pathway for the Ancestors and the Ursa Major Asterism

Algonquian Thanksgiving

Colonists in Virginia observed Algonquians “dancing around posts” each fall, with gourd rattles and leaves or branches, each dancer taking a turn to present a sheaf and make a short speech. Each post likely represented a harvest month—April through October, with each dancer singing the praises of the spirit responsible for a particular food plant or other natural resource harvested during that month in the annual cycle.

Algonquian Thanksgiving

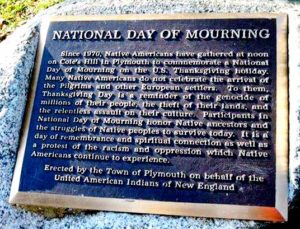

The naked figure in the center of the “Thanksgiving” depiction with the two women is very likely the shaman, and perhaps the grouping represents the concept of fecundity over all [7]. Thanksgivings as feast days were a Native American tradition that the Pilgrims recognized or adopted in a kind of syncretism, blending the Christian tradition of giving thanks to God for one’s daily bread with the pagan harvest festivals of Neolithic Europe and the Native American tradition of giving thanks to the spirits for the fruits of their seasonal harvests. In Plymouth, Massachusetts, today, the “First Thanksgiving” is commemorated from the Native American point of view in light of history, in a plaque proclaiming it as a National Day of Mourning.

The true circumstances of the “First Thanksgiving” belie the tale we older folk learned in school about turkeys and pies and brotherhood between Indians and settlers. Forgive me if I am repeating myself here, but there were no turkeys or pies, but swans and geese and potatoes. It was Massasoit’s 92 warriors who hunted deer to supply the feast with meat. Upon hearing a volley of the colonists’ guns, fired in salute, the Wampanoag had arrived at Plimoth Plantation prepared for possible combat.

National Day of Mourning

Observations of the moon’s cycles were also important. The Algonquian solar calendar was 13 months of 28 days, while the lunar calendar was 12 lunations of 29 days. The solar and lunar calendars were reconciled by observing at 11-day intervals. Eleven days denotes the difference between the length of the solar year and the 12 lunations, and that difference can be used to predict in advance when a leap month (or 13thmonth) was needed [8].

Algonquian Lunar Calendar

| POSITION | MONTH | ENGLISH | ALGONQUIAN |

| Early Winter | January | Old Moon, Moon after Yule | Wolf Moon, Ice Moon, Greeting Maker Moon, Forgiveness Moon |

| Mid-Winter | February | Wolf Moon, Candles Moon | Snow Moon, Hunger Moon, Storm Moon, Breaking Branches Moon |

| Late Winter | March | Lenten Moon, Chaste Moon | Worm Moon, Crow Moon, Sugar Moon, Sap Moon, Death Moon, Moose Moon, Spring Maker Moon |

| VERNAL EQUINOX: Day and night equal in length; start of growing season. | |||

| Early Spring | April | Egg Moon | Pink Moon, Sprouting Grass Moon, Fish Moon, Seed Moon, Waking Moon, Birds Returning Moon, Sugar Maker Moon |

| Mid-Spring | May | Milk Moon | Flower Moon, Corn Planting Moon, Hare’s Moon, Earth Moon, Field Maker Moon |

| Late Spring | June | Flower Moon, Rose Moon | Strawberry Moon, Honey Moon, Planting Moon, Hoer Moon |

| SUMMER SOLSTICE: Days longer than nights; height of growing season. | |||

| Early Summer | July | Hay Moon, Mead Moon | Buck Moon, Thunder Moon, Grass Cutter Moon, Blueberry Maker Moon |

| Mid-Summer | August | Grain Moon | Sturgeon Moon, Red Moon, Green Corn Moon, Dog Moon, Lightning Moon, Meal Maker Moon |

| Late Summer | September | Fruit Moon, Barley Moon | Harvest Moon, Corn Moon, Corn Maker Moon |

| AUTUMNAL EQUINOX: Day and night equal in length; end of growing season. | |||

| Early Fall | October | Harvest Moon | Hunter’s Moon, Travel Moon, Dying Grass Moon, Blood Moon, Falling Leaves Moon |

| Mid-Fall | November | Hunter’s Moon | Beaver’s Moon, Frost Moon, First Snow Moon, Freezing River Maker Moon |

| Late Fall | December | Oak Moon, Moon Before Yule | Cold Moon, Long Night’s Moon, Winter Maker Moon |

| WINTER SOLSTICE: Nights longer than days; height of winter. | |||

Among the Stones

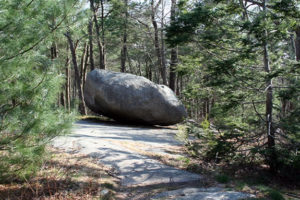

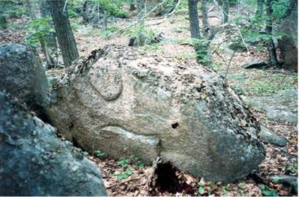

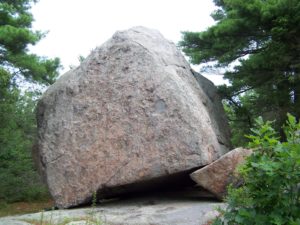

Places like Pole Hill were ceremonial landscapes besides, with glacial erratics modified into effigy stones as objects of veneration, and other stones split, piled, or moved to invite or bar spirits or to make enclosures as sacred spaces. These were objects and places where observers watched the sky, shamans meditated, people gathered for ceremonies, and the young made spirit quests and dreamed dreams. Dreams and the waking dreams called vision quests were achieved through fasting, smoking or ingesting hallucinogenic substances, exposure to the elements, and dehydration.

Shamans rocked boulders balanced on bedrock to make a loud noise and shake the earth, announcing messages from spirits and perhaps scaring or thrilling young initiates wandering around in search of their personal totems. Stones were a medium of spiritual expression.

Shamans rocked boulders balanced on bedrock to make a loud noise and shake the earth, announcing messages from spirits and perhaps scaring or thrilling young initiates wandering around in search of their personal totems. Stones were a medium of spiritual expression.

People passing by a place respectfully dropped a stone where an important event had occurred in the life of the community—an act of bravery or sacrifice, a treaty or trade agreement, a tragedy or mystery—creating over time great stone cairns [9]. I wrote a two-part article on the subject of “spirit rocks” on Cape Ann, published in volumes 55 (1) Autumn 2022 and 55 (2), Winter 2022-2023 in the Journal of the New England Antiquities Research Association.

Examples of possible effigy stones on Cape Ann (Ravenswood, Dogtown, Andrews Woods, Pole Hill)

It cannot be denied that Native Americans in New England intentionally raised, perched, piled, stacked, balanced, rocked, carved, inscribed, split, and wedged- open rocks for symbolic and practical purposes. However, the provenance and authenticity of rock piles we see today are uncertain. Some were formed by retreating glaciers, modified by colonists or modern developers, or even created by townies and tourists over the past 300 years. Skeptics have claimed that only Europeans (Vikings, Celts, or English colonists)—or aliens from outer space—had the technology to move such massive boulders, much as Egyptians were believed to have been incapable of building their pyramids or Easter Islanders of erecting their moai (giant stone heads). But archaeologists have confirmed many stone constructions as authentically Native American, and, of course, they could use the laws of gravity and motion as well as any human to make megaliths or move mountains. The Megaliths in Manchester-by-the-Sea may have been tilted up during glacial retreat, but they would have had spiritual significance to Indigenous people interacting with them. [10].

It cannot be denied that Native Americans in New England intentionally raised, perched, piled, stacked, balanced, rocked, carved, inscribed, split, and wedged- open rocks for symbolic and practical purposes. However, the provenance and authenticity of rock piles we see today are uncertain. Some were formed by retreating glaciers, modified by colonists or modern developers, or even created by townies and tourists over the past 300 years. Skeptics have claimed that only Europeans (Vikings, Celts, or English colonists)—or aliens from outer space—had the technology to move such massive boulders, much as Egyptians were believed to have been incapable of building their pyramids or Easter Islanders of erecting their moai (giant stone heads). But archaeologists have confirmed many stone constructions as authentically Native American, and, of course, they could use the laws of gravity and motion as well as any human to make megaliths or move mountains. The Megaliths in Manchester-by-the-Sea may have been tilted up during glacial retreat, but they would have had spiritual significance to Indigenous people interacting with them. [10].

The Megaliths (formerly Agassiz Rock)

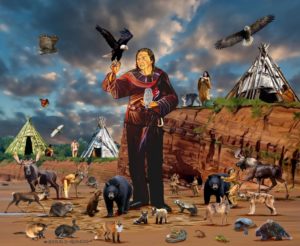

Culture Heros

Algonquian cosmology and astrology are supported by stories and legends (some would say myths, to which some Indigenous People today would object), like the story of the three hunters (and their dog) chasing the sky bear and wounding it, its blood causing the leaves to turn red in fall, and the bear recovering in hibernation until the stars rise again in spring. In some versions the bear dies and its cub emerges from the den to renew the cycle of the circumpolar stars. Other stories feature tricksters and transformers—powerful beings and culture heroes, such as Gluscap (Glooskap, Kluscabi), who, along with the Great Spirit, created the earth, caused the origins of all things, instructed the animals, outwitted harmful spirits, kept nature in balance, and taught people how to adapt. Great respect was accorded to creatures able to transform themselves—shape-shifters–such as butterflies and frogs.

Glooscap with the Animals, Glooscap Heritage Center, Millbrook, Nova Scotia

Culture heroes included the giant, Hobomoc, who broke the Great Beaver’s dam, which flooded the valleys with water from the melting glacier at the end of the last Ice Age, and Wittun, who caused fresh water to come forth from rocks on the ridge lines to heal the valleys so people live there.

In the Beginning

Algonquian creation stories illustrate how the people came to terms with a natural and supernatural world they saw as imperfect and irrational (or disappointing and crazy), a conclusion completely opposite from that drawn by Puritans, in which a monotheistic god had intentionally created perfect order in the universe. Missionaries elevated Gitchi Manitou, the Great Spirit, to stand alone for the Christian god and his son and the holy ghost, much to everyone’s consternation. The possible return of someone from the dead–a ghost–was much feared. While possibly revealing missionary influences, Indigenous creation stories nevertheless contrast in interesting ways with the Judeo-Christian origin myth represented in Genesis [11].

Here is an abridged version of the Algonquian creation myth in which Manito creates the world on the back of a turtle, collected by an ethnographer in 1949. The Abenaki teller of the creation story prefaced it as follows [12]:

In my dream, I awakened, I turned to my side and saw the morning sun shining through a dew-covered spider web. So beautiful it was! It was filled with sparkling color, a million tiny lights in a hand’s breadth. A black and yellow spider was busy repairing a tear in the web from an insect that got away. The spider stopped and stared at me. It spoke to me in a tiny little voice and said, “This is a Dream Net. It only lets good dreams through. This hole was left by the dream you are dreaming now!”

Maheo, the Great Manito, Creator, became tired of the endless silence and darkness at the beginning of time. He wished to fill endless space with light and the joyful movement of life. Out of his great hands flew the sparks of the creation fire, filling endless space with light. He bid Mikchich, the Great Turtle, to emerge from the water and become land. With his strong hands he molded a creation world with mountains and valleys. He put the waters all where they should be and set white clouds sailing in the blue sky. Then, the Manito looked at all this and said to himself, “This is the creation world I want. Now I will fill this place with the happy movement of life.”

The Great Manito thought about what kind of life he would make. He carefully considered how he would make a perfect web of life with each creature just so and in perfect place. Each should have a perfect way of life and all would be happy. Long into that last night before creation began, the Manito thought out a perfect plan, and then he fell asleep, exhausted. Soundly did he sleep, and his sleep was filled with dreams. Strange dreams he had.

The Great Manito dreamed of a strange creation world, filled with strange beings, not at all what he had planned. They walked on four legs, some on two. Some creatures crawled, some flew with wings. Some of these swam with fins. There were plants spreading out, covering the ground everywhere. Insects buzzed, geese honked, and moose bellowed. Men sang and called to each other in this strange dream. This was a world with no design at all, no order. This was a bad dream. No world of creation could be this imperfect, this mad!

And then the Great Manito awakened to see a porcupine nibbling on a twig. To his dismay he realized the world of his dream had become Creation!

Thus, even for gods, dreams could come true. Interpreting dreams, along with assisting the healer, were among the shaman’s chief duties. Dreamcatchers were replications of the proverbial spider’s web and were woven, decorated, and hung as objects of individual expression. Small dreamcatchers were hung on cradleboard frames in front of babies’ faces to ensure they had pleasant dreams.

Dreamcatcher

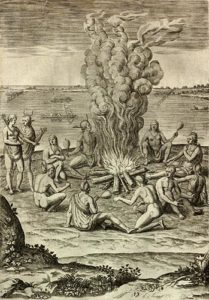

While the aim of Puritan religion was redemption of the soul, the central theme of traditional Algonquian belief and expression was the attainment, conservation, and use of spiritual power. Your manitou came from your kinship and ancestry, your spirit guide or totem, personal visionary experiences or dreams, special talents or skills, and your luck or success in forming relationships or making a living. Spiritual power also came from touching sacred objects and being in sacred places, and from handling dangerous or unusual objects containing spiritual power (such as scalplocks taken as coups, poisonous snakes, quartz crystals or polished gemstones, and specially carved effigies of spirits in stone or clay). You could protect your spiritual power through right living, ritual observances, such as sweat lodge purification and the making of offerings to the spirits, honoring ancestors, and using amulets or personal medicine bundles. Power also came from communally shared expressions directed toward spirits, such as praying, chanting, dancing, and drumming—the powwow [13].

Colonists understood that Native Americans already had their own traditions of spiritualism and worship. John White drew Jamestown “Indians Praying”, for example—Algonquians chanting and shaking rattles together around a sacred fire intended to invoke beneficial spirits and carry prayers or wishes to the Great Spirit. The Europeans at first identified with these expressions but later came to see them as invalid and ultimately as Satanic [14].

“Indians Praying”

Life and Death

White’s watercolors of Algonquians in Virginia shows how they stored and attended to bodies of their dead in special wigwams or raised smokehouse-like structures for several days. After funerary rites, the bodies—no longer in rigor mortis and beginning to decompose—were then “flexed” into a fetal position (sometimes referred to erroneously as a “sitting” posture) and wrapped in woven fiber cloth (or cornstalk mats or birch bark in the north). Sometimes the flexed body was placed inside a specially made basket coffin and otherwise was covered with woven mats along with selected possessions as grave goods. A warrior, for example, might be buried with his arrows, quiver, bow, and coups. The body, mat bundle, or basket coffin was then interred in the ground in a communal unmarked earthen mound or in a stone chamber in an upland area designated as sacred. In some groups, bodies were later ceremonially disinterred, defleshed, and the bones painted with red ochre, bundled together, and reburied in ossuaries [15].

Algonquian charnal house

Archaeological evidence confirms that early Algonquian burials in the Northeast were placed on north- or northeast-facing level ground or in low mounds in sandy or otherwise easily-dug soil overlooking a body of water—a river, lake, or the sea. Bodies were placed flexed on the side, facing either east, with the feet facing east to facilitate passage to the spirit world, or facing southwest, where the ancestors of Late Woodland immigrants resided. In the Algonquian medicine wheel, north represented (among other things) the wisdom and spirituality of old age and east represented rebirth. The presence of burial grounds supports the likely presence of permanent or regular seasonal habitation sites.

In Agawam and elsewhere, some burials were exhumed by colonists and paraded as an act of disrespect, as happened with Masconomet’s remains until citizens intervened. Native American gravesites have been found in many parts of Essex County, including Andover, Beverly, Salem, Haverhill, Georgetown, Newbury, Ipswich, Hamilton, Gloucester, Manchester, Rowley, and Salisbury. The most extensive finds have been made in Marblehead, like Ipswich the likely site of a large permanent village by the time of English contact [16]. Today the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act protects Indigenous burials from being disturbed in any way and mandates the return of any remains and grave goods or sacred objects from museum collections. Some Native Americans today would object to my even talking about this subject, and for this I apologize. I mean no disrespect.

Philip Freneau (1752-1832), a romantic poet of the Revolutionary period, was impressed with the spirituality of Native American burials. In his 1787 poem on the subject, he reimagines the flexed burial with grave goods as the individual “seated” with peers, preparing for a hunt, as in life. References to “sitting chiefs” in colonial accounts and early American literature refer to mortuary remains. Freneau’s poem also refers to a great rock and an old elm tree, additional features of the landscape that Algonquians would likely have chosen to site a burial ground. Here is a portion of the poem, “The Indian Burying Ground” [17]:

In spite of all the learned have said,

I still my old opinion keep;

The posture that we give the dead,

Points out the soul’s eternal sleep.

Not so the ancients of these lands–

The Indian, when from life released,

Again is seated with his friends,

And shares again the joyous feast.

His imaged birds, and painted bowl,

And venison, for a journey dressed,

Bespeak the nature of the soul,

Activity, that knows no rest.

His bow, for action ready bent,

And arrows, with a head of bone,

Can only mean that life is spent,

And not the finer essence gone.

Thou, stranger, that shalt come this way,

No fraud upon the dead commit,

Yet, marking the swelling turf, and say,

They do not lie, but here they sit.

Here, still a lofty rock remains,

On which the curious eye may trace

(Now wasted half by wearing rains)

The fancies of a ruder race.

Here, still an aged elm aspires,

Beneath whose far-projecting shade

(And which the shepherd still admires)

The children of the forest played.

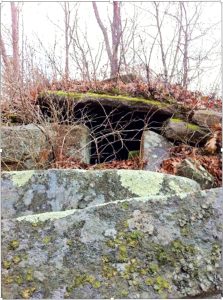

Mounds and Chambers in Massachusetts

Unexcavated mounds and looted chambers are all that remain of pre-contact Native American burials in Massachusetts. Specific site locations are kept confidential to prevent further desecration. The undisturbed burial mound shown here is in northern Essex County, while the disturbed stone chamber is in southern Worcester County. Nipmuc descendants believe their ancestors built the chamber as an ossuary for their dead. An empty stone chamber in Rockport, called Rowe’s Tomb, likely served as an Indigenous ossuary. (Lt. Rowe was never buried there and it is fairly inaccessible, i.e., not some colonists’ larder.)

Mound in Gloucester

Burial practices changed over time. Archaic period burials in permanent sand dunes and ledges above riverbanks, for example, predate Woodland period burials in clam middens and earthen mounds on upland terraces. Funerary practices simplified, especially as a consequence of epidemics, when large numbers of dead taxed tradition. Ultimately, single Christian-style burials without headstones replaced flexed individual burials, which in turn had replaced family or group burials in chambers or mounds [18].

Burial practices changed over time. Archaic period burials in permanent sand dunes and ledges above riverbanks, for example, predate Woodland period burials in clam middens and earthen mounds on upland terraces. Funerary practices simplified, especially as a consequence of epidemics, when large numbers of dead taxed tradition. Ultimately, single Christian-style burials without headstones replaced flexed individual burials, which in turn had replaced family or group burials in chambers or mounds [18].

In Cape Ann and Essex, more than 50 Native burials have been discovered and reported over the past 300 years. Add to that the unreported, as well as undiscovered, graves that were destroyed or are still here. Pawtucket skeletons were taken from known sites in Annisquam, Bay View, Dogtown, Wingaersheek, Castleview, Coffin Beach, Manchester-by-the-Sea, Argilla Road in Ipswich, Coles Island, Hog (Choate) Island, and Castle Neck, for example, and many more from sites in Ipswich north and Salem-Beverly south. As noted earlier, today burials are protected by NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. As a consequence of this legislation, many skeletal remains and grave goods have been returned to tribal councils for ceremonial reburial in sacred ground [19].

“Rowe’s Tomb” in Rockport

Based on descriptions written by Roger Williams and others, Algonquians in New England had less elaborate funerary practices than those in Virginia. According to a second-hand colonial account of an Agawam (Pawtucket) funeral in Ipswich during Masconomet’s time [20]:

When the mourners came to the grave, they laid the body near by, then sat down and lamented. He observed successive tears on the cheeks of old and young. After the body was laid in the grave, they made a second lamentation; then spread the mat, on which the deceased had died, over the grave; put the dish there, in which he had eaten, and hung a coat of skin on an adjacent tree. This coat none touched, but allowed it to consume with the dead. The relatives of the person, thus buried, had their faces blacked, as a sign of mourning.

Mourning Paint

Tantasqua Graphite Mine in Sturbridge

The blacking worn by the Agawam mourners was possibly obtained from a mine in Middleton or was traded for from the Tantasqua (or Tantiusques) graphite mine in Sturbridge, MA—today a historic 57-acre open space reservation. Black face paint for mourning—a commodity in great demand in New England trade—was made from graphite (carbon) that the Nipmuc mined, and the mine is still there on Rte. 124 and Lead Mine Pond Rd. The carbon was powdered and mixed with animal fat to make black greasepaint. Algonquians used red greasepaint, from iron oxide or powdered hematite and animal fat, as warpaint. White paint was made from calcite dust and kaolin clay. In 1636 the governor of Ipswich, John Winthrop Jr. bought Tantasqua from the Nipmuc. Other native mines he acquired around that time for the Massachusetts Bay Colony included various bog iron pits, including the one in West Gloucester, and a native copper mine in Topsfield [21].

The blacking worn by the Agawam mourners was possibly obtained from a mine in Middleton or was traded for from the Tantasqua (or Tantiusques) graphite mine in Sturbridge, MA—today a historic 57-acre open space reservation. Black face paint for mourning—a commodity in great demand in New England trade—was made from graphite (carbon) that the Nipmuc mined, and the mine is still there on Rte. 124 and Lead Mine Pond Rd. The carbon was powdered and mixed with animal fat to make black greasepaint. Algonquians used red greasepaint, from iron oxide or powdered hematite and animal fat, as warpaint. White paint was made from calcite dust and kaolin clay. In 1636 the governor of Ipswich, John Winthrop Jr. bought Tantasqua from the Nipmuc. Other native mines he acquired around that time for the Massachusetts Bay Colony included various bog iron pits, including the one in West Gloucester, and a native copper mine in Topsfield [21].

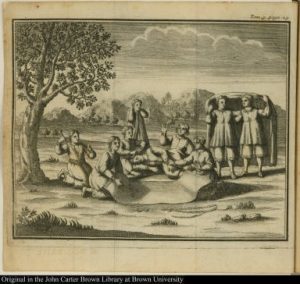

Colonial depiction of an Agawam burial

As noted in a previous section, this colonial depiction of an Agawam burial shows relatives mourning as they place a body on its side to be flexed and wrapped in a woven fiber mat prior to burial in the earth [22]. The shaman kneels at the left under an oak tree, regarded as sacred, performing a funerary rite, interceding with the spirits on behalf of the spirit of the deceased and aiding the deceased’s passage to afterlife in the skyworld. After the mourning period the people will take great care not speak the deceased’s name, so as not to call back the spirit or impede its passage to the skyworld. In the picture the mourners’ dress reflects Puritan influence.

As noted in a previous section, this colonial depiction of an Agawam burial shows relatives mourning as they place a body on its side to be flexed and wrapped in a woven fiber mat prior to burial in the earth [22]. The shaman kneels at the left under an oak tree, regarded as sacred, performing a funerary rite, interceding with the spirits on behalf of the spirit of the deceased and aiding the deceased’s passage to afterlife in the skyworld. After the mourning period the people will take great care not speak the deceased’s name, so as not to call back the spirit or impede its passage to the skyworld. In the picture the mourners’ dress reflects Puritan influence.

Considering that this is how the Algonquians in Essex County made sense of their world, we now must ask, how exactly did they lose their land? And what is the real story of the founding of Gloster Plantation?

Notes and References

1. Contemporary works describing Algonquian religion include Kathleen Bragdon’s Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650 (1999), Robert Hall’s 1997 book, An Archaeology of the Soul: North American Indian Belief and Ritual, and William Simmons’ Spirit of the New England Tribes: Indian History and Folklore 1620-1984(1984). Algonquians and Christianity is the subject of Chapter 8 of this book. For an anthropological perspective on Algonquian resistance to Christianity in the 17thCentury and an explanation of the manitou concept, see Neal Salisbury’s 1982 Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the making of New England 1500-1643.See also the 1983 review of his book by Alden T. Vaughn in The New England Quarterly (54), and Salisbury’s 2003 article in Ethnohistory50 (2): “Embracing Ambiguity: Native Peoples and Christianity in Seventeenth-Century North America”. Colonial sources on Algonquian religion include Roger Williams, William Bradford, Edward Winslow, Thomas Morton, John Winthrop, John Eliot, Daniel Gookin, and other 17thand early 18thCentury observers, referenced earlier in this book. See, for example, Karle Schleiff’s article, Stoneworks, Corn and Calendars, regarding Bartholomew’s Gosnold’s observations of native sun watching in 1602, at http://ancientlights.org.html.

2. Authentic expressions of magic realism in Algonquian spiritualism appear in early native texts. See especially the stream-of-consciousness-like account of Joseph Nicolar (1893), published in 2007 as The Life and Traditions of the Red Man: A Rediscovered Treasure of Native American Literature, edited by Annette Kolodny and Charles Norman Shaw. See alsoClara Sue Kidwell’s article, Ethnoastronomy as the Key to Human Intellectual Development and Social Organization. In Native Voices: American Indian Identity and Resistance(2003). For an appreciation of the concept of ceremonial time in Algonquian culture, see John Hanson Mitchell’s 1984 book, Ceremonial Time: Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, and a review of this book in 1987 by Curtiss Hoffman in the Bridgewater Review5 (2), available online at http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol5/iss2/16/.

3. Sources on animism and animatism include Part 23 of the Encyclopedia of Religion(Hastings, 2003) and Graham Harvey’s 2005 book, Animism: Respecting the Living World. For an example of the pervasiveness of animistic beliefs, read an in-depth study by Michel-Gerald Boutet, The Great Long Tailed Serpent: An Iconographical study of the serpent in Middle Woodland Algonquian culture (2011), at http://www.academia.edu/3537441/The_Snake_motif_in_Algonquian_Culture. Classic ethnographic works on Algonquian shamanism include Frank G. Speck’s Penobscot Shamanism, in Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association 6 (1919) and Frederick Johnson’s Notes on Micmac Shamanism, in Primitive Man 16 (1943). See also William S. Simmons’ Southern New England Shamanism: An Ethnographic Reconstruction, in Papers of the Algonquian Conference7 (1976).

4. The chart in this chapter of selected Algonquian spirit names with English translations is from English and French missionary data on the Narraganset, Massachuset, Nipmuc, Abenaki, and Maliseet, as presented in the work of Frank Waabu O’Brien (Moondancer), and Julianne Jennings (StrongWoman). See their 2007 book, ACulturalHistoryof the NativePeoplesof SouthernNewEngland:Voicesfrom Pastand Present(BauuPress). Note that my chart omits the diacritical marks and alternative spellings in the original work, which may be recovered as desired from “Spirit Names and Religious Vocabulary” at http://www.bigorrin.org/waabu10.htm.

5. The germinal work on Algonquian ceremonial landscapes is by James Mavor and Byron Dix in Manitou: The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization(1989). See also Edwin C. Ballard and James W. Mavor, Jr., 2006, Case for the use of above surface stone constructs in a Native American ceremonial landscape in the Northeast, NEARA Journal40 (1), and Edward L. Bell, Discerning Native Placemaking: Archaeologies and Histories of the Den Rock Area, Lawrence and Andover, Massachusetts, Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut75 (2013). The solar calendar at Pole Hill (Sunset Hill) in Riverview, Gloucester, is presented in a 2014 paper by Mary Ellen Lepionka and Mark Carlotto, Evidence of a Native Solar Observatory in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society76 (1). For other examples of solar observatories in New England, see articles by Kenneth C. Leonard Jr.: Calendric Keystone? Archaeoastronomy10 (1987) and Identification and Preliminary Analysis of a Late Woodland Ceremonial Site in Southeastern Massachusetts, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society71 (1) (2010); William Hranicky’s 2001 article, Difficult Run Petroglyphs: A Prehistoric Solar Observatory in the Potomac River Valley of Virginia, Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Virginia 56 (2); Dix and Mavor’s Two Possible Calendar Sites in Vermont, in Archaeoastronomy in the Americas (1981); Tim Fohl’s Integrated Wetland-Dry Land Features with Astronomical Associations, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 71:1 (2010); Edwin C. Ballard’s For Want of a Nail: An Analysis of the Function of Some Horseshoe or U-Shaped Stone Structures. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society60 (2) (1999); Frederick W. Martin et al., Archaeo-Astronomical Prospecting at the Moose Hill Stone Chambers. Archaeology of Eastern North America 40 (2012); and Michael S. Nassaney, The Significanceof the Turners FallsLocality in Connecticut River Archaeology, in The Archaeological Northeast, Mary Ann Levine, Kenneth E. Sassaman, and Michael S. Nassaney, eds. (1999). In 2013, because of its significance as a native solar calendar and ceremonial landscape, the Turners Falls site was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

6. Useful general sources on archaeoastronomy are John Edwin Wood’s Sun, Moon, and Standing Stones(1978), George E. Lankford’s Reachable Stars: Patterns in the Ethnoastronomy of Eastern North America (2007), and William Tyler Olcott’s classic Star Lore of all Ages: A Collection of Myths, Legends, and Facts concerning the Constellations of the Northern Hemisphere (1911).Key works on archaeoastronomy in the civilizations of the Southwest, Mexico, and Mesoamerica include John A. Eddy, Astronomical Alignment of the Big Horn Medicine Wheel. Science 174 (1974); Munro S. Edmonson, The Book of the Year: Middle American Calendrical Systems (1988); Anthony Aveni, Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico (1980); and Stephen C. McCluskey, Historical Archaeoastronomy: The Hopi Example, in Archaeoastronomy in the New World, A.F. Aveni, ed. (1982). Direct linkages between New England and Mesoamerican ceremonial landscapes were proposed in 2006 by Timothy Fohl and Kenneth Leonard in a paper, Similarities of Ceremonial Structures in New England and Mesoamerica, presented at the 73rdAnnual Meeting of the Eastern States Archaeological Federation jointly with the Massachusetts Archaeological Society and The New England Antiquities Research Association in Fitchburg, MA. For the significance of particular constellations in Native American ceremonial landscapes, see, for example, Glenn N. Kreisberg’s Serpent of the North: The Overlook Mountain/Draco Correlation (2010), at http://www.grahamhancock.com/forum/KreisbergG5.php; and the now classic works of Lynn Cesi, Watchers of the Pleiades: Ethnoastronomy Among Native Cultivators in Northeastern North America, in Ethnohistory 25 (4) (1978) and Von Del Chamberlain, When the Stars Came Down to Earth: Cosmology of the Skidi Pawnee Indians of North America (1982).

7. The “Thanksgiving” picture is an engraving by Theodore de Bry (1590) of a drawing that first appeared in Thomas Hariot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia(1588). Having feast days for giving thanks was traditional in Algonquian culture, and thanksgiving feasts were conducted two or more times a year. The notion that there was a “first Thanksgiving” at Plymouth Plantation is an ethnocentric accounting based on William Bradford’s journal, now embedded in the American mind. Some surviving Native American communities make a point of not celebrating the Thanksgiving designated as a national holiday.

8. The lunar calendar presented here is a compilation from diverse sources based on French and English ethnolinguistic data for northern and southern New England and Canada, including interpretations by Christine Sioui Wawanoloath (http://westernabenaki.com/dictionary/moons.php), Marge Bruchac (http://www.vermontfolklifecenter.org/childrens-books/malians-song/additional_resources/seasons_moons.pdf), and the Old Farmers Almanac (http://www.almanac.com/content/full-moon-names).

9. Many communities in New England have ethnohistorical accounts as well as physical examples of Native American rocking or balanced stones, cairns, effigy boulders, rock shelters, petroglyphs, and other stoneworks, some authenticated as Native American in origin and others shrouded in mystery or controversy. Mary and James Gage have controversially attempted to classify and describe native stoneworks in Handbook of Stone Structures in Northeastern United States(2008). See also Mary Gage’s article, New England Native American Spirit Structures, in the Spring 2013 issue of the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (1). See also articles and photographs by Peter Waksman, for example, at http://indianrockpiles.weetu.com/articles/IndianRockPiles.html

10. Agassiz Rock in Manchester-by-the-Sea is featured as the cover photo of the Mavor and Dix book Manitou. Others who argue for Native American skill in creating monumental stoneworks that have survived to this day include Noel Ring, Ken Goss, and Ken Leonard in their paper, Northeast Native North American Astronomy and Engineering, read at the Eastern States Archaeological Federation Annual Meeting on October 31, 2013 (South Portland, ME). Skeptics’ views are represented in Kenneth L. Feder’s Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum(2011). Walam Olum is a purported and much debated native pictographic text expressing Lenape ancient history and mythology. Feder also includes Mystery Hill in Salem, NH, and Gungywump Swamp in Groton, CT, as examples of dubious archaeology, mainly because of documented or assumed tampering with those sites over the centuries and interpretations that are not evidence-based. See David P. Barron and Sharon Mason’s book, The Greater Gungywamp: A Guidebook(1994), David Goudsward and Robert E. Stone’s America’s Stonehenge: The Mystery Hill Story.(2003), and Mary Gage’s America’s Stonehenge Deciphered(2006). Other sources may be found on the “America’s Stonehenge” website at http://www.mysteryhillnh.info/html/bibliography.html.

11. See Nicholas Campion’s Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions(2012) and Frank G. Speck’s descriptions in Penobscot Transformer Tales, International Journal of American Linguistics1 (1918): https://archive.org/details/jstor-1262934; Wawenock Myth Texts from Maine, in Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution:43 (2) (1928); and Penobscot Tales and Religious Beliefs, Journal of American Folklore6 (1935). For an appreciation of the role of dreams and dreaming in Algonquian culture and the significantly contrasting world views of colonists and Indians, see Ann Marie Plane’s Dreams and the Invisible World in Colonial New England: Colonists, Indians, and the Seventeenth Century(2014). Among the many sources for particular Algonquian myths and legends are William Simmons’ papers, Return of the Timid Giant: Algonquian Legends of Southern New England, Algonquian Conference13 (1982); and Genres in New England Indian Folklore, Algonquian Conference15 (1984). A classic source is Charles G. Leland’s Algonquin Legends of New England(1884). You can read stories about Gluscap’s (Glooskap’s) exploits at http://www.native-languages.org/glooskap.

12. The creation myth presented here appears in Gerard Rancourt Tsonakwa and Tolaikia Wapitaska’s The Dreamer, in Welcome the Caribou Man: A Catalogue of Images and Stories from the San Diego Museum of Man:12-13 (1992).

13. Acquiring spiritual power or protection through the touching of sacred, dangerous, or emblematic objects is an example of “contagious magic”. Contagious magic is also used in witchcraft to cause harm or good to a person by manipulating associated objects, such as hair clippings, fingernail parings, or articles of clothing. Cultural anthropologists contrast contagious magic with “sympathetic” or “imitative” magic, in which rituals, such as fertility rites, serve to ensure that “like produces like”. Colonial perceptions of Algonquian spiritual practices and the social institution of the powwow are taken up in greater detail in Chapter 8.

14. John White’s watercolors and Theodore deBry’s engravings of them depict many aspects of Algonquian life in Delaware, Virginia, and North Carolina. White’s depictions of Indians praying, an Algonquian charnal house, and others are in the British Museum. See Paul Hulton and David Beers Quinn,The American Drawings of John White 1577-1590, Vol. II, Reproductions of the originals in colour facsimile and of derivatives in monochrome (1964). For an appreciation of the historical and ethnographic importance of these images, see Lisa Heuvel’s 2010 article, Looking with Clearer Vision: The Significance of John White’s Watercolors, at the website of the Jamestown and Yorktown Settlement & Victory Center: http://www.historyisfun.org/Significance-of-John-White.htm.

15. A principal source on Algonquian burial practices is Erik Seeman’s Death in the New World: Cross-Cultural Encounters 1492-1800(2011). For particular archaeological reconstructions, see, for example, Francis P. McManamon, James W. Bradley, and Ann L. Magennis’ CRM Study No. 17 (1986), The Indian Neck Ossuary(North Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior) and Gary D. Shaffer’s Nanticoke Indian Burial Practices: Challenges for Archaeological Interpretation, in Archaeology of Eastern North America33 (2005).

16. A definitive, if not up to date, source on burials in Massachusetts is Mary J. Haaker’s An Annotated Bibliography of Late Woodland Burials in Massachusetts, in Archaeological Quarterly6 (Fall 1984). Documented burial mounds survive in Salisbury, Newburyport, Nashoba, Lakeville, Cape Ann, and other sites in Massachusetts, and Indian burial grounds have been preserved in various localities on Cape Cod and the islands. Many 17thcentury colonial graveyards have native burials incorporated in them or on a perimeter.

17. Read the rest of Freneau’s poem at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46094/the-indian-burying-ground.

18. Indian burials on Cape Ann and the surrounding area have been reported periodically since the Civil War Period. See, for example, F. W. Putnam, On Indian remains in Essex County, Proceedings of the Essex Institute 5:186 (1867). Reports of burials in the media include, for example, the Gloucester Daily Times, November 13, 1940: Cape Ann Rich in Indian Relics Rotarians Told by N. Carleton Phillips.

19. For a full explanation of NAGPRA, see the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. National NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act): http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/INDEX.HTM. See also The Law and American Indian Grave Protection on the website of the Indian Burial and Sacred Grounds Watch at http://www.ibsgwatch.imagedjinn.com/learn/massachusettslaw.htm. The Massachusetts Historical Commission has a paper on What To Do When Human Burials Are Accidentally Uncovered, at http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/knowhow4.pdf.

20. The description and illustration of the Agawam burial originally came from Roger Williams’ 1643 work, A Key into the Language of America, accessible online at https://archive.org/details/keyintolanguageo02will. The description was widely copied, and a similar account appears in the travel correspondence of John Dunton, an English bookseller, in which he claims to have witnessed an Agawam burial near Wonasquam on Cape Ann in 1686 (See Letters Written from New England. Prince Society Publications Issue 4 (1966). It is unknown whether Dunton was reporting what he saw or repeating what Williams wrote.

21. The Tale of Tantiusques 1644-1909, is in The Winthrop Papers(Reel 38 Box OS2) in the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Societyin Boston. A description of the Indians’ copper mines in Topsfield, by Mrs. G. Warren Towne, appears in The Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society, 2 (1892). For further perspective of Native American mining, see Mary Ann Levine’s papers:Native copper, hunter-gatherers, and northeastern prehistory (1999), at http://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations/AAI9709620; and Native Copper in the Northeast: An Overview of Potential Sources Available to Indigenous Peoples, in The Archaeological Northeast(1999).

22. The original of this etching is in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University in Providence, RI.