We know Indigenous people lived on Cape Ann through physical, documentary, and linguistic evidence. By physical evidence—archaeological remains—their presence here can be attested for at least the last 10,000 years and longer in other parts of Essex County. Early sites are under water now because of sea level rise since the end of the last Ice Age. At the height of the last Ice Age, the Laurentide glacier covered Cape Ann to a depth of about half a mile. So much water was taken up in the glacier that Ipswich Bay, Jeffreys Ledge, Sandy Bay, Massachusetts Bay, Cape Cod Bay, Stellwagen Bank, George’s Bank, and the Grand Banks were all dry land. Those sea bottoms hold the record of some of the earliest humans to reach the Western Hemisphere, as well as of the Paleoindian mammoth hunters who followed them. Bones dredged or seined in Cape Ann waters tell us that until around 10,000 years ago, mastodons and their hunters lived here.

Over the past 5,000 years many more archaeological sites in coastal New England have been lost to sea level rise, which has submerged as much as 60 meters (over 197 feet) of elevation of land that people once occupied. Land joined Plum Island to the mainland, for example, which must have been prime real estate for the first people. Cape Ann was without islands then, a single landmass with glacial outflow plains, its rivers not yet “drowned” in tidal estuaries or Ipswich Bay.

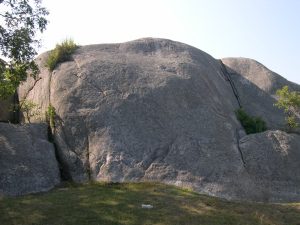

Striations in the bedrock at Halibut Point and other sites are evidence of the Laurentide’s passing. Glacial movement scoured away Cape Ann’s topsoil, subsoil, and sedimentary layers, grooved the igneous bedrock beneath, and in its wake left only glacial till (unsorted clay, gravel, sand, silt, and boulders). You can see where the glacier scored Cape Ann’s plutonic outcrops, such as Tablet Rock in Stage Fort Park and Squam Rock in Annisquam.

The glacier also dragged rocks across the landscape and dropped them all over the cape, some from as far away as Newfoundland. These are the boulders known as glacial erratics, such as Raccoon Rocks in Dogtown. Erratics, many of which later Native Americans moved or modified for their own purposes, dot the landscape. Cape Ann also contains many rock dumpsites called terminal moraines and shaped deposits of till known as eskers and drumlins. For example, Choate Island in Essex Bay and Pigeon Hill in Rockport are drumlins. Kettles are holes made by calved blocks of glacial ice that became covered with outwash debris and later melted. Some kettles became freshwater lakes, such as Walden Pond, while others became part of the new shorelines.

We have physical evidence

Physical evidence for human occupation consists mainly of stone tools and ceramics, which archaeologists classify as diagnostic of certain periods or people. Archaeologists describe the occupation of North America in terms of four main cultural periods prior to European contact, each with overlapping early, middle, and late phases: the Pre-Clovis, Paleoindian, Archaic, and Woodland Periods. The spans of time are demarcated by observable changes in technology and other evidence of cultural change.

Dates for these periods vary for different geographic regions, because the dating of sites is affected by the geological history of an area and the different rates and extents of people’s migrations. In addition, dates may vary depending on the dating method used. Half-life dating of rocks and artifacts based on radioactive decay, such as C14 or potassium to argon, and methods such as tree ring analysis, provide absolute measures of time. Relative measures of time, such as seriation (changes in style) and stratigraphy (changes in deposition) date sites or artifacts in terms of their age in relation to other sites or artifacts. Both kinds of dating are needed to tell the story of what happened in the distant past.

Dates also vary by the particular kinds of sites being dated, the systems used for classifying artifacts, the quality of the samples being dated, and the theoretical orientations of the scientists doing the dating. Dates also constantly change as new evidence is unearthed or better methods of testing are developed. At one time it was thought the Western Hemisphere was not occupied until around 10,000 years ago, for example, but now we have confirmed dates of four times that age and more.

A Revised Chronology for Southern New England

PERIOD YEARS BP (Before the Present)

Contact 750 — 250

Late Woodland 1,500 — 500

Middle Woodland 2,500 — 1,500

Early Woodland 3,500 — 2,500

Late Archaic 5,500 — 3,500

Middle Archaic 8,500 — 5,500

Early Archaic. 10,500 — 8,500

PaleoIndian 16,000 — 10,500

Pre-Clovis. 50,000? – 16,000

The Archaeology of Cape Ann

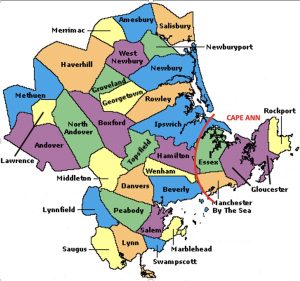

Artifacts diagnostic of each period have been found on Cape Ann and vicinity. For example, projectile points, pottery sherds, clay pipes, stone pendants, and other features characteristic of the Woodland period have been found at Great Neck and Castle Hill in Ipswich; in Essex on Chebacco Lake and Hog (Choate) Island; at Coffin Beach and Wingaersheek Beach; Wheeler’s Point and Riverview; Rust Island and Pearce Island; Wigwam Point, Lighthouse Beach, and Adams Hill in Annisquam; Dogtown including Annisquam Heights; Lobster Cove and Goose Cove; Plum Cove, Lane’s Cove, and Folly Cove; Squam Hill, Pool Hill, Old Garden Beach, and Land’s End in Rockport; and elsewhere.

Archaeologists and collectors have worked here from the post-Civil War period to today. In the 1870s Frederick Ward Putnam of Harvard University and the American Museum of Natural History became the first to conduct professional archaeology in Essex County. Putnam reported on sites in Ipswich, Essex, Beverly, Salem, and Newbury. His colleague Warren K. Moorehead, famous for his work on Cahokia and the so-called Red Paint People of Maine, identified 18 shell heaps, two burial grounds, and hundreds of artifacts on Castle Neck in Ipswich, including stone tools, pieces of pottery, fossilized corn, and beaten copper. Moorehead was head of the R.S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology in Andover between 1902 and 1920 and eventually reported his findings on Castle Neck in a 1931 paper on his Merrimack Archaeological Survey.

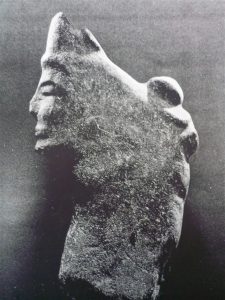

Most of the archaeological evidence for Native sites on Cape Ann comes from surveys and excavations conducted in the first half of the 20th century. Other members of the Harvard University, Peabody Museum, and American Museum of Natural History circle who contributed to the archaeology of Essex County included Charles Willoughby and Marshall Saville. Willoughby’s book on New England antiquities included an Abenaki sculpture exhumed from mud at the head of Lobster Cove in Annisquam. The three-dimension sculpture was found by S. Foster Damon in 1929, described by Willoughby in 1935, and and purchased for Harvard University by Ernest Hooten for $100 in 1940. The head shows a woman in profile, wearing a traditional Eastern Abenaki-style peaked cap. She has an infant secured to the nape of her neck with a tump line to her forehead. Her distinctive peaked headdress identifies her and presumably her maker as Eastern Abenaki– perhaps a Mi’Kmaq (“Tarrantine”). It is possible that after a hundred years or more of competition for coastal real estate, Eastern Abenaki were occupying Pawtucket sites on the coast of Cape Ann as they were being abandoned in the 1680s.

Sources on the “Annisquam Head” include Willoughby (1935), Bragdon (1996), and Teele and Sargent (2013).

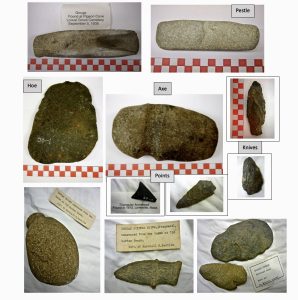

Marshall Saville and his brother Foster were Rockport native sons. They worked on sites of the Ohio Mound Builders and ancient Maya kingdoms of Mexico. Marshall studied at Harvard and taught archaeology at Columbia University and later directed the Museum of the American Indian, then known as the George Gustav Heye Foundation, in New York. Saville founded the Sandy Bay Historical Society in Rockport, where his local collection is stored. His collection of local artifacts spans the Archaic and Woodland periods and includes assemblages of tools for hunting, fishing, and gardening; for processing wood, flesh, hide, fiber, and food; and for quarrying, pecking, and grinding stone. His finds came from the Rockport Golf Club grounds, Mill Brook Meadow, the Headlands, Whale Cove, Gap Head, Flat Point, Pigeon Cove, Andrews Point, Old Garden Beach, Lanesville, Folly Cove, and Land’s End.

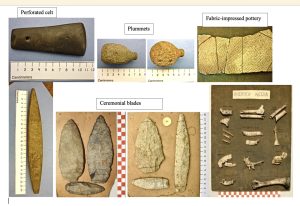

Examples of artifacts from the Saville Collection (Courtesy Sandy Bay Historical Society)

The ethnologist Frank G. Speck with Abenakis on Bear Island in Maine (from Speck’s Papers at the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley MA, Box 1)

In the 1920s, Frank G. Speck, a University of Pennsylvania ethnologist who specialized in Eastern Woodland Indian cultures and summered on Riverview Road in Gloucester, and his student Frederick Johnson conducted an archaeological survey along the Annisquam River. They identified occupation sites and shell middens at Curtis Cove, Thurston’s Point, Wheeler’s Point and on the river islands—Cow Island, Rust Island, and Pearce’s Island. Some of their finds reportedly went to the Heye Foundation in New York but were subsequently lost. Speck went on to make important contributions to the anthropology of Native people of the Northeast, and Johnson became a director of the American Anthropological Association and the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology in Andover. In the 1940s he led the excavation of the famous Indigenous fish weir under the Mutual Life building on Boylston St. in Boston’s Back Bay.[1]

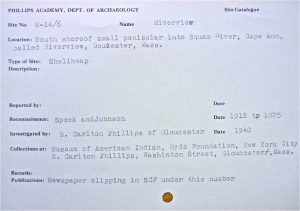

In the 1930s N. Carleton Phillips followed up on the discoveries of Speck and Johnson and made some discoveries of his own. He excavated living floors and fire pits in Riverview on the Annisquam River and in Riverdale along the Mill River and carried out bushel baskets full of potsherds, animal and bird bones, and stone tools. Phillips was president of the Russia Cement Company (LePage’s Glue) in Gloucester and an avid amateur archaeologist and collector. Surviving examples of his collections are stored in the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester as the Phillips Collection and the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough as part of the Chadwick Collection. He never published his findings but left notes of talks he gave in 1940 and 1941 at meetings of the Gloucester Rotary Club. Phillips exhumed Indigenous burials at Coffin Beach, Wingaersheek, and Annisquam and sent them to Harvard for forensic analysis. Among his finds were two rows of preserved corn hills and a rock shelter on Coles Island and 18 wigwam living floors in Babson’s Pasture on Mill River, still visible in 1940.[2]

Indigenous Sites Excavated by N. Carleton Phillips

- Riverview (4 sites incl. Wheeler’s Pt. shell midden)

- Russ [Rust] Island

- Merchant [Pearce] Island

- Cole Island (Cole’s Farm)

- Coffin Beach (Herrick’s Farm)

- Farm Point

- Wingaersheek (Coffin’s Farm, 2 sites)

- Presson’s Point (on Little River, West Parish)

- Mill River (Babson’s Pasture, Riverdale)

- Annisquam (2 sites: Bent’s Pasture, Adams Hill)

- Lanesville (Langsford St.)

- Fishermen’s Field (Stage Fort Park)

- Dogtown

Phillips donated some of his artifacts to the Cape Ann Scientific and Historical Society, a forerunner of the Cape Ann Museum, but other parts of his collection were discarded by his widow, who gave some to another collector by the name of Benjamin Chadwick, who donated them to the Bronson Museum, a forerunner of the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough.

Some Artifacts from the Phillips Collection at the Cape Ann Museum (Courtesy Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester MA)

Examples of Phillips’ artifacts in the Chadwick Collection at the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough, MA (Courtesy the Massachusetts Archaeological Society)

History of Archaeology around Cape Ann

1867-1922 F. W. Putnam, Warren K. Moorehead

1897-1925 Marshall Saville, George Heye

1917-1928 Frank Speck, Frederick Johnson

1920s-1930s Charles Willoughby, Ernest Hooton

1938-1942 N. Carleton Phillips, Foster Saville, Henry Collins

Douglas Byers, Carleton Coon

1947-1949 Ripley Bullen, Vaccaro brothers at Bull Brook

1950s Roland Wells Robbins in Dogtown

1960s Sarah Keller, Robert Matz, Eugene Winter

1970s Frank McManamon, MHC Salvage archaeology

1980s Brian Robinson, Vic Mastone

1990s Irving Soucholeki in Dogtown, Marine archaeology

2000s Mass. Historical Commission (MHC) CRM projects

Scientific and technological developments during World War II transformed archaeology. With Carbon 14 dating, new methods of excavation, and new protocols for salvage archaeology and cultural resource management (CRM), archaeology was no longer a gentleman’s hobby or collector’s club. The field nevertheless continued to benefit from the work of avocational researchers. In the late 1940s, for example, it was amateur archaeologists who discovered Bull Brook, a world-famous Paleoindian site in Ipswich, the Winter site, a Contact Period site at Essex Falls. The largest collection of finds from Bull Brook, curated by noted archeologist Brian Robinson, are stored in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. The Essex Falls site was excavated by Eugene Winter, one-time president of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society and former curator at the R. S. Peabody Museum in Andover, where his finds are stored.[3]

Some Artifacts in the Cape Ann Collection of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem

Important sites often are reexcavated or reinterpreted decade to decade. Bull Brook, for example, has been reexamined three times, most recently in the 1990s, and one of Phillips’ sites at Wingaersheek, in the Cape Ann Campgrounds on the Jones River Salt Marsh, was reexcavated in the 1960s. Artifacts from the Cape Ann Campgrounds are stored in the Harvard Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge as the Matz Collection.[4]

Cultural Resource Management (CRM) surveys have been conducted here under the auspices of the state archaeologist, the Massachusetts Historical Commission, the National Park Service, and private firms specializing in public archaeology. CRM excavations undertaken as part of water, sewer, transportation, and commercial development projects have identified several Indigenous sites on Cape Ann. Two have confirmed radiocarbon dates for the Early and Late Woodland Periods (3,000 and 750 years ago).[5] The results of such projects are seldom made public, however, often at the request of the city or state, tribal councils, or the corporation or other private property owners, for fear of looting or desecration or costly construction delays. The sequestering of information about pre-Contact archaeological sites has contributed to public ignorance of Indigenous history here. This is in contrast to the celebration of discoveries of Colonial Period sites and shipwrecks. Cape Ann has provided many opportunities for underwater archaeologists.[6]

Some significant Cape Ann artifact collections are in private hands. One of the largest belongs to Tom Ellis of Gloucester, skipper of the historic schooner the Thomas E. Lannan. Artifacts in the Ellis Collection come from Coffins Beach, Coles Island, Conomo Point, Cross Island, Spit Island, and Hog Island and include stone weights, sinkers, gouges, axes, celts, hammerstones, pestles, abraders, chisels, awls, scrapers, knives, projectile points, pendants, and paint stones. The Annisquam Historical Society at 7 Walnut St. in Gloucester also owns some significant artifacts, including a Paleoindian spear point, miniature ceramic votive vessels, quartz projectile points, and a piece of platform pipe carved from catlinite (pipestone).[7] The Manchester Historical Society likewise has a few locally collected artifacts. The Ipswich Museum, in contrast, has hundreds of artifacts in crated storage.

Examples of artifacts in the Ipswich Museum

Much artifactual evidence for Cape Ann has been lost to private collectors. Sites are also lost through urban development and the ignorance of artifact hunters. For a few hundred years now, people have been picking up interesting stones and shards on beaches, pathways, riversides, and backyards to discover they have found an ancient artifact of some kind. Dogtown’s historic cellar holes have been plundered innumerable times. Private homes, libraries, and local museums in every New England town have artifacts on windowsills or mantels or in cabinets or display cases that were lifted from their archaeological contexts to be collected as mere objects. Out of context, however, they tell us little or nothing about the people who made them and how they lived. Information about their living areas, movements, daily life, use of space, resource use, food preparation, funerary practices, and other cultural activities is lost. That information does not reside in an artifact. It is in the earth itself.[8]

Colonial cellar hole in Dogtown, Gloucester (Photo courtesy Mark Carlotto)

It can be a revelation to see how an archaeological dig is properly conducted. Sites are located through ground surveys, surface finds, historical references, aerial photography, ground-penetrating radar, side sonar, or by accident in foundation digging or roadworks. Once identified, sites are carefully surveyed and marked out in meter squares. Test pits or trenches may be dug to locate the edges of a site. Each square is then excavated evenly, sometimes only centimeters at a time, using appropriate tools for the site conditions–from trowels to bulldozers. Each layer and everything found in each layer of each square is carefully photographed, mapped to a grid through triangulation, and identified by GPS coordinates. The layers give us the history of occupation and sequence of human activities, for it is the lived-upon earth that tells the story: how a shelter was built and repaired, where people killed or cooked or cached food, where and when they gathered together and for how long. The dirt in the earth stores the impressions of the holes they dug, the marks their hoes and axes made, the postholes of their dwellings and other constructions, the weaves of their baskets, their very footsteps, and sometimes their fates.[9] Their surviving graves, ceremonial stone landscapes, astronomical sight lines, petroglyphs, and earthworks are other kinds of physical evidence.

It can be a revelation to see how an archaeological dig is properly conducted. Sites are located through ground surveys, surface finds, historical references, aerial photography, ground-penetrating radar, side sonar, or by accident in foundation digging or roadworks. Once identified, sites are carefully surveyed and marked out in meter squares. Test pits or trenches may be dug to locate the edges of a site. Each square is then excavated evenly, sometimes only centimeters at a time, using appropriate tools for the site conditions–from trowels to bulldozers. Each layer and everything found in each layer of each square is carefully photographed, mapped to a grid through triangulation, and identified by GPS coordinates. The layers give us the history of occupation and sequence of human activities, for it is the lived-upon earth that tells the story: how a shelter was built and repaired, where people killed or cooked or cached food, where and when they gathered together and for how long. The dirt in the earth stores the impressions of the holes they dug, the marks their hoes and axes made, the postholes of their dwellings and other constructions, the weaves of their baskets, their very footsteps, and sometimes their fates.[9] Their surviving graves, ceremonial stone landscapes, astronomical sight lines, petroglyphs, and earthworks are other kinds of physical evidence.

Masconomet’s English grave site on Sagamore Hill, South Hamilton MA

We have documentary evidence

In addition to this abundant physical evidence, we have documentary evidence in many forms. Town archives and early town histories often lack conspicuous information about Indigenous occupation in coastal New England. The official history of Cape Ann is notably silent on the subject, for example, and it has been claimed that no Indians were here when the English attempted to settle in Gloucester in 1623. It was alleged the “Indians” had all died out from disease or killed each other off, and in any case were only nomads who may have stumbled upon Cape Ann while filtering down through the trees when hunting deer—because arrowheads have been found here and there—but otherwise they never lived here.[10] That is the story. In the face of archival denial, documentary evidence for their life here has tended to be indirect, off-site, unofficial, inferred, or second hand—but the information is there if one is tenacious enough to locate it in dusty vaults, leaking basements, cracking microfilms, secret repositories, and countless personal papers, along with the official contents of municipal, state, and national archives.

Documentary Evidence of Indigenous Settlement on Cape Ann and Beyond

- Explorers’ accounts, e.g.,:

“Ye Names of Ye Rivers”

Samuel de Champlain, Capt. John Smith

- Accounts of first settlers, e.g.,:

Dorchester Company, testimonials of Old Planters

A Cape Ann Indigenous guide brought Conant’s party to a Native village in Beverly.

Manifests for Essex County Indian trade goods

Roger Conant, John Endicott, and John Winthrop requested shipments of goods for use in Indian trade at Cape Ann, Salem Village, and Charlestown.

William Wood, John Josselyn, Samuel Maverick, Thomas Morton

- Correspondences, e.g., :

Reports of the first governors to the English Crown

John White, William Bradford, and Roger Williams wrote letters about the payment of Dorchester Company debts through trade with the Indians on Cape Ann.

Letters of John Winthrop and John Winthrop Jr. refer to Indians led by Masconomet.

John Dunton wrote home about the village of Wonasquam in Gloucester.

- Reports of missionaries about their efforts to convert Native people to Christianity.

French missionaries, e.g, Fr. Rale, Fr. Mathevet

Puritan clerics and missionaries, e.g., Richard Mather, John Eliot

Church records

- Massachusetts Bay Colony records:

Laws for living and trading with Indians

Oath of 1644 in Salem district court

Records of criminal, civil, and probate court proceedings

- Land records:

Endicott’s purchase of “hoed land” for Gloster Plantation

Indian deeds in the Salem Registry of Deeds

Mass. Bay Colony records of Indian land transactions

- Memoirs, e.g.,:

John and Ebenezer Pool

Charlotte Lane and Manton Merchant

Rufus Choate

- Town records:

Minutes of Selectmen’s meetings

Newspaper accounts

Censuses and tax records

Vital records and Military accounts

Early town histories

European explorers and fishing entrepreneurs reported how they saw and interacted with Indigenous people on Cape Ann before the English came to settle. The earliest documentary evidence is an anonymous paper in the British Library from the archives of King Charles II, referred to as the Egerton Manuscript, entitled “Ye Names of Ye Rivers and Ye Sagamores Yte Inhabit Upon Them.” It names all the large tidal rivers and their principal Native villages from the Penobscot to the Annisquam, observed in a sail-by. The Annisquam River and its village are recorded as Wenesquawam, later corrupted to Wonasquam.

The earliest laws and court cases refer to the Indigenous people, their lands, corn, leaders, rights, movements, enemies, possession of firearms, practice of religion, terms of trade, uprisings, treaties, crimes, susceptibility to inebriation, and need for fences. The English recorded the doings of Masconomet of Agawam and Wonasquam, who is buried on Sagamore Hill in South Hamilton. Mass. Bay Colony land records note that Gloster Plantation was leasing land from the Indigenous people here in exchange for bushel baskets of Indian corn.[12]

John Babson’s iconic history of Gloucester makes no reference “Indians”, however, and Gloucester’s archives contain only two references to them. In 1682 the Selectmen voted to ask the townspeople to distinguish between “the strange Indians” (those displaced by conflict with colonists elsewhere) and “the ones who live among us”. Then in 1684 the Selectmen voted to ask the townspeople to refrain from acts of vigilantism against “the Indians who live among us”. Whether the Selectmen acted on their vote and with what consequence was not recorded. In 1686 a London bookseller on a visit from Ipswich to the Indian village of Wonasquam in Gloucester wrote home that the Indians here were in mourning over the death of an important person and were abandoning their village. All the quitclaim deeds of 1700-1701 to Gloucester and all the other cities and towns in Essex County further attest to Native precedence and presence here throughout the 17th century.[13]

Documentary evidence also appears in residents’ memoirs, such as Ebenezer Pool’s 1823 recounting of his grandfather’s stories about the Indians who lived in a large village in Riverview north of Pole Hill; Manton Merchant’s recollection of Indians coming to camp and dig clams each summer on Pearce Island; Charlotte Lane’s description of Indians who came to visit and paddled dock to dock in Annisquam selling baskets, brooms, and herbal remedies. Society page notices in the Gloucester Magazine, Gloucester Telegraph, Gloucester Advertiser, and Gloucester Daily Times announce visits of Indians arriving and camping at their traditional “haunts”—Phillips Ave. in Pigeon Cove, Rust Island and Little River in West Gloucester, Bent’s Pasture in Annisquam, Sayward Ave. at the head of the harbor—and how visiting Indians helped put out Gloucester’s Great Fire of 1830.[14] The last recorded visit, of Penobscot from Indian Island in Maine, was in 1833, by which time President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act—in which all Native people were forcibly relocated west of the Mississippi—had gone into full effect.

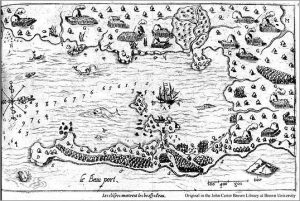

We have cartographic and linguistic evidence

In another kind of documentary evidence, we have surviving place names in the language of the Native people who lived here, preserved in somewhat corrupted form from the earliest times of encounter. Some of these place names can be found on the earliest maps of the northeast coast. Champlain’s map of Gloucester harbor in 1606 is cartographic evidence of Indigenous occupation there. He drew their wigwams and wrote about his interactions with Indigenous people at Whale Cove in Rockport in 1604 and later in Gloucester Harbor, including conversations with a Cape Ann sagamore by the name of Quiohamanek.[11]

Champlain’s Map from Les Voyages showing wigwams on Gloucester Harbor is an example of cartographic evidence for Indigenous occupation of Cape Ann.

When the English came, their earliest maps include Indigenous place names and other references to Native presence, such as “Old Garden” beach (i.e., fields planted in “Indian Corn”) and “Castle” hill (i.e., sites of Native forts). Other than cartographic clues, documentary evidence of Native presence is in the ship manifests of vessels carrying trinkets to trade with “the Indians at Cape Ann”, and in the letters and testimonies of the first governors, clerics, and settlers of Cape Ann, Plymouth, Salem Village, Ipswich, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Like the physical archeological evidence and documentary evidence, cartographic and linguistic evidence confirms the fact that Indigenous people were living here before the time of English contact, despite the lack of reference to them in town records of the 17th century and Victorian Era histories. Indigenous place names include Agawam, Quascacunquen, Wonasquam, Agamenticus, Chebacco, Naumkeag, Winniahden, Wingaersheek, and others.[15] Surviving early colonial place names likely referring to activities of Native people here include Cornhill Street—the original name of Middle Street where Indigenous people had planted corn, Clay Pit Landing—in the Jones River Saltmarsh, and Samp Porridge Hill—near the end of Revere St. in Annisquam, referring to a Native corn mush dish called samp or nausamp.[16] So what do our Algonquian place names really mean? And what can they tell us about the Indigenous people who lived here?

What do local Algonquian place names really mean?

Notes and References

[1] Speck’s article, Massachusetts Indians, especially relating to Cape Ann, was published in the Gloucester Daily Times, August 4, 1923. The Museum of the American Indian, now in Washington, DC, says it has no archaeological acquisitions in its Heye Foundation collection under the names of Speck or Johnson. Johnson’s work preserved in the R. S. Peabody Museum in Andover and the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough does not include material from Cape Ann. Physical evidence also comes from the following sources: Putnam, F. W. 1867. On Indian remains in Essex County. Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Vol. 5 (186): 197-199 (Salem, MA); 1869. On shellheaps in Essex County, Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol. 1 (12) (Salem, MA); 1872. Account of archaeological researches at Jeffries Neck, Ipswich, Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol. IV: 79-83 (Salem, MA); 1872. Indian Relics from Beverly. Bulletin of the Essex Institute 3: 123-125. Moorehead, Warren K. 1910. The Stone Age in North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1913. The Red-Paint People of Maine. American Anthropologist 15 (1): 33-50. Moorehead, Warren K. & Benjamin L. Smith. 1931. Merrimack Archaeological Survey: A Preliminary Paper. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (Harvard University). See also Willoughby, Charles C. 1935 (Reprinted 1973). Antiquities of the New England Indians, with notes on the ancient cultures of the adjacent territory. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Teele, Rita & Deedy Sargent. 2013. Mystery in Stone: The Puzzle of the Annisquam Effigy. Presentation of Sept. 27, 2013 to the Annisquam History Discussion Group, Annisquam Village Library: youtube.com/watch?v=TdFl8493QUU&feature=youtu.be. Saunders, Brigham Clarence. 1935. Marshall Howard Saville. Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 45 (2): 151-153. Lothrop, S. K. 1924. Tulum: The Archaeological Study of the East Coast of Yucatan. (Introduction cites participation of Marshall Saville; cf. Maya funerary heads in the Deluge 8 firehouse in Annisquam, property of the Annisquam Historical Society), The Carnegie Institution Publication No. 335, Washington, DC. See also Saville, Marshall H. 1919. Indian Notes and Monographs. Museum of the American Indian Heye Foundation 5 (1) (New York); 1920 Indian Relics from Newburyport and Gloucester. American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1 (Boston). The Sandy Bay Historical Society is at 40 King St. in Rockport (http://rockporthistory.org/). See Lepionka, Mary Ellen. Fall 2017. Speck in Riverview. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (2): 60-70.

[2] Lepionka, Mary Ellen. Fall 2013. Unpublished papers on Cape Ann Prehistory. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (2): 45-92. N. Carleton Phillips never published his extensive findings and the documentation for his surveys and excavations (maps, site reports, photographs) have not been found. He gave talks, however, for example at Rotary club luncheons, describing his activities and finds, and unpublished transcripts of these talks are in the library of the Cape Ann Museum at 27 Pleasant St. in Gloucester. See Phillips, N. Carleton. 1940 and c. 1941. Unpublished untitled transcripts of talks given in Gloucester (MA) on the archaeology of Cape Ann. Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Museum. Also: Gloucester Daily Times, November 13, 1940. Cape Ann Rich in Indian Relics Rotarians Told (Carleton Phillips, 23 samples of pottery from Riverview).

[3] Eldridge, William and Joseph Vacaro. July 1952. The “Bull Brook” Site, Ipswich, Mass. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 13 (4): 39-43. Byers, Douglas S. April 1954. Bull Brook—A Fluted Point Site in Ipswich, Massachusetts. American Antiquity 19 (4): 343-351; Grimes, John R., William Eldridge, Beth G. Grimes, Antonio Vaccaro, Frank Vaccaro, Joseph Vaccaro, Nicolas Vaccaro and Antonio Orsini. Fall 1984. Bull Brook II. In Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 12: New Experiments upon the Record of Eastern Paleo-Indian Cultures: 159-183. Eastern States Archaeological Federation. Robinson, Brian S., Jennifer C. Ort, William A. Eldridge, Adrian L. Burke, and Bertrand G. Pelletier. July 2009. Paleoindian aggregation and social context at Bull Brook. American Antiquity 74 (3): 423-447. Gene Winter’s 2007 article referring to Essex Falls, Additional Information on Late Archaic Caches in Essex County, MA, appears in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 68 (1): 28-32.

[4] Keller, Sarah. 1965. Matz Collection of artifacts from West Gloucester. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Matz, Robert. 2013. Gloucester, MA. Personal Communications about the Contact Period archaeological site at Wingaersheek, May 1 and August 7, 2013.

[5] The Massachusetts Historical Commission’s public records include their Reconnaissance Survey Town Reports, for example, the 1985 Reconnaissance Survey Town Report: Gloucester (http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/townreports/Essex/glo.pdf). For a useful comparison see also the reconnaissance surveys for other nearby cities and towns. Modern CRM studies documenting prehistoric activity or occupation have been conducted in Ipswich (Suvalis et al. 1979); Beverly-Salem (Ritchie et al. 1996); Gloucester (Thompson 1978; Leveillee 1988); and Essex (Macpherson et al. 1999; Raber et al. 1980/1981). Specific sites with prehistoric significance have been identified at Castleview in West Gloucester (Dwyer & Edens 1995), Cogswell’s Grant in Essex (Wheeler and Stachiw 1996), Thurston Point in Riverview (Leveillee 1988), and Little River in Gloucester (Chartier 2001).

[6] Lynch, Kerry, University of Massachusetts Archaeological Services. Identifying the Submerged Native American History of the Northeast: The Archaeology of Inundated Occupations. Talk given on April 11, 2012 at the Weston Observatory, Weston, MA; Riess, Warren C. 1998. Possible Shipwreck and Aboriginal Sites on Submerged Land (in) Gloucester Massachusetts, Darling Marine Research Center, University of Maine. http://www.mass.gov/czm/dredgereports/1998/dmmp-98-02.pdf. See a 2019 profile of underwater archaeologist Vic Mastone at https://slis.simmons.edu/blogs/lis476/2019/04/07/meet-vic-mastone-director-and-chief-archaeologist-for-the-massachusetts-board-of-underwater-archaeological-resources/. Mastone, Vic. Underwater Archaeology: Mystery Shipwreck on Coffins Beach, Gloucester: https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarch/arch15/Coffins-Beach_Shipwreck_15.pdf.

[7] Lepionka, Mary Ellen. Spring 2018. Maritime Archaics in Essex Bay: The Saville and Ellis Collections. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 79 (1): 11-21. Ellis, Tom. 2013. Old Bray Rd., Gloucester, MA. Personal Interview regarding his collection of Cape Ann artifacts and artifacts from Bull Brook, May 8, 2013. Tom Ellis’s collection also includes around 25 artifacts from Carlton Hoyt’s collection from Bull Brook, Ipswich, an assortment of Archaic and Woodland Period points. A large private collection I have not seen, reported in Elizabeth Waugh’s book, The First People of Cape Ann (Dogtown Books, 2005), is the property of Judith Juncker of Annisquam, Gloucester. Another large private collection I have not seen is held by James Oliver of Gloucester. O’Keefe, Tom. 2013. Annisquam Historical Society, Gloucester, MA. Personal Communications about Indian artifacts in the Annisquam Museum, March-October, 2013. See http://www.annisquamhistoricalsociety.org/.

[8] Carlotto, Mark. 2015 The Cellars Speak: The Old Cellars and What They Tell Us about Dogtown and Its People. Gloucester, MA. Artifacts found on beaches, in streambeds, or in plow zones probably have already been disturbed or removed from their cultural contexts, but high-density concentrations of finds in those locations may nevertheless signal the presence of a site. Artifacts eroding out of riverbanks or sand dunes may signal the presence of undisturbed archaeological sites. By law people must report discoveries of suspected sites or skeletal remains to the State Archaeologist through the Massachusetts Historical Commission. If remains are discovered accidentally during excavation on private or public property, work must be stopped and authorities notified. See the Massachusetts Historical Commission web site: http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcleg/legidx.htm. State laws relating to Archaeology, which mirror federal laws, include M.G.L. Ch. 9 ss.26-27C and 950 CMR 70. Laws pertaining to Native American Burials are M.G.L. Ch. 7 s.38A, Ch. 9 ss.26A & 27, Ch. 38 s.6., and M.G.L. Ch. 114 s.17. Information about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) see also Indian Burial and Sacred Grounds Watch: http://www.ibsgwatch.imagedjinn.com/learn/massachusettslaw.htm.

[9] See the Society for American Archaeology web pages on Methods of Gathering Data at http://www.saa.org/ForthePublic/Resources/EducationalResources/ForEducators/ArchaeologyforEducators/MethodsofGatheringData/tabid/1347/Default.aspx. A good summary of new conceptual approaches in archaeology appears in Amber Johnson’s 2004 book, Processual Archaeology: Exploring Analytical Strategies, Frames of Reference, and Culture Process. For a perspective on the applications of these methods, see Dean Snow’s classic text, The archaeology of Native North America (1980, 2009). Because sites are destroyed as they are dug, precise locations, descriptions, measurements, and photographs are essential for reconstructing whatever took place there. Earth removed from an excavation is sifted through screens to recover small items such as bone fragments, teeth, or beads. Each artifact is labeled, catalogued, drawn or photographed, and may then be removed for study or conservation. At construction sites, archaeological findings may be simply documented before work resumes, or removed to prevent their destruction, or arrangements may be made for the site to be conserved. Workers in all the sciences associated with archaeology strive to prepare and preserve their data for all time in hopes that future scientists will be able to apply new knowledge and technologies to make better sense of it—much as cold case files with carefully packaged evidence await justice.

[10] Glouceser Historical Time-Line 1000-1999 (Mary Ray, 2002, Gloucester Archives Committee) refers only to fears of Indian raids, Indian wars, and exhumations of Indian relics and bones. “Indians” are not mentioned at all in John Babson’s 1860. History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann: Including the Town of Rockport (Samuel Chandler, Procter Brothers) nor in his 1891 Notes and additions to the history of Gloucester…Gloucester, Mass. M. V. B. Perley: https://archive.org/details/notesadditionsto00babs.

[11] Another chapter describes in more detail the voyagers and explorers who first reported the presence of Native people on the New England coast including Cape Ann. The earliest documentary evidence is “Names of the Rivers and the names of ye cheife Sagamores yt inhabit upon Them from the River of Quibequissue to the River of Wenesquawam.” (“from the Penobscot to the Annisquam”), n.d. (circa 1602-1610); British Library, Egerton Manuscripts 2395 [Fol. 412]. For Samuel de Champlain’s account, see The works of Samuel de Champlain, H.H. Langdon and W. F. Ganong, Eds. 1922, 6 vols., Champlain Society, Toronto, Canada. Reprinted in 1971 by the University of Toronto Press, H. P. Biggar, ed: http://www.champlainsociety.ca. (Champlain wrote volume 1 in 1599, volume II in 1603, volume III in 1613, and the last three volumes in 1632.) See also Voyages of Samuel de Champlain, a translation of Les Voyages edited by Edmund F. Slafter. The best translation in my opinion, however, is Otis, Charles Pomeroy. 1878. Memoir of Samuel de Champlain,Volume II 1604-1610 (Prince Society, Boston): canadachannel.ca/HCO/index.php/Champlain’s_Voyages,_Translated_by_Charles_Otis,_Vol._II_1604-1608#cite_note-230.

[12] See, for example, William Bradford’s Letters in his History of Plymouth Plantation, 1856, Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 11, Series 4: 1-89 (the unabridged Fulham manuscript with letters), Boston, Little, Brown, and Company; and Governor William Bradford’s Letter Book. 1906. Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants, Boston; Winthrop, John. 1790. Journal of the transactions and occurrences in the settlement of Massachusetts and the other New-England colonies, from the year 1630 to 1644, written by John Winthrop … and now first published from a correct copy of the original manuscript. Hartford, CT: Elisha Babcock. For colonial laws relating to Native Americans in Essex County, see Book of the General Laws of the Inhabitants of the Jurisdiction of New-Plimoth, and Generall Laws of the Massachusetts Colony, revised and published, by the Order of the General Court (1632-1676) http://www.princelaws.pdf; also http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/tlc0200.jpg; Massachusetts General Court. 1814. The charters and general laws of the colony and province of Massachusetts. Boston, MA: B.T. Wait and Co.; General Laws of the Massachusetts Colony Revised and Published by Order of the General Court in October 1632 – Revised edition, November 1675. http://www.usingessexhistory.org/primarydocuments/institute07/princelaws.pdf; Vaughan, Alden T., and Deborah A. Rosen, eds. 1998, Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and Laws, 1607-1789: https://www.academia.edu/3154519/Southern_New_England_vol._19_and_New_England_North_and_West_vol._20_in_EARLY_AMERICAN_INDIAN_DOCUMENTS_Treaties_and_Laws_1607_1789. For court cases see Dow, George Francis, ed. 1911-1921. Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts (8 vols.), Volume 1. Salem, MA: Essex Institute; Massachusetts Court of Assistants, John Noble and John F. Cronin, eds. 1901. Records of the Court of assistants of the colony of the Massachusetts Bay 1630-1692, Volume I; Massachusetts Historical Society, Collections of. 1856. Salem Court of Assistants Records; Salem County Court Records 1672 (Nov. 6: 34); 1677 (June 26:34).

[13] Masconomet’s career is taken up in another chapter. A general source is Smith, Bonnie Hurd. 2008. Masconomet, Sagamore of Agawam. North Shore Life Magazine. The sagamore and his wife and unknown others are buried on Sagamore Hill in S. Hamilton, which is protected under the stewardship of the Essex County Greenbelt Association: www.ecga.org, which restricts access. Pawtucket leasing of is in Wright, Harry Andrew. 1941. The Technique of Seventeenth Century Indian Land Purchases. Essex Institute Historical Collections 77: 185-197; Eno, Joel N. 1906. The Puritans and Indian Land. Magazine of History with Notes and Queries: 274-281, Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings 12 (1873): 356; Hannon, Christopher W. Summer 2001. Indian Land in Seventeenth Century Massachusetts, Historical Journal of Massachusetts 29 (2); Leavenworth, Peter S. June 1999. “The Best Title That Indians Can Claime”: National Agency and Consent in the Transferal of Penacook-Pawtucket Land in the 17th Century. New England Quarterly 72 (2): 275-300. Massachusetts General Court Book of Indian Records for Their Lands. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Commission Archives. See also Gloucester Town Records, Minutes of Selectmen’s Meetings for 1862 and 1864 in the Gloucester Archives. Dunton, John. 1686. Letters Written from New England. Prince Society Publications Issue 4, N. Stratford, NH: Ayer Publishing (1966 edition). Native deeds are recorded in a special collection at the Salem Registry of Deeds. 2013. See a Summary of Native American Deeds for Essex county at: http://www.salemdeeds.com/nativeamericandeeds/indiandeedsummary_9-20-06.pdf. See also Sidney Perley. 1912. The Indian Land Titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. Salem: Essex Book and Print Club.

[14] Pool, Ebenezer. 1823. Pool Papers, Vol. I. Typescript Ms, in the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA (original is in the basement of the Sandy Bay Historical Society, Rockport, MA). Lane, Charlotte Augusta. 1925. Indians. Unpublished handwritten deposition in the Gloucester Archives, Gloucester (MA) City Hall. Merchant, Manton E. 1942. Unpublished handwritten deposition about Indians in the Gloucester Archives, Gloucester (MA) City Hall. Newspaper accounts of Indians visiting traditional sites on Cape Ann include the following: In 1822 Maine Indians still summered on Cape Ann (1978) Gloucester Magazine 1 (4), p. 14; Indian Rights, Gloucester Telegraph, January 22, 1831; Cape Ann Advertiser, July 15, 1879, A small delegation of the Penobscot Indians…has pitched its tents [on Phillips Ave.] and resumed the basket trade as aforetime; Cape Ann Advertiser, September 8, 1882, The Indian encampment at Pigeon Cove…folded its tents like the Arabs and quietly slipped away; Gloucester Daily Times, July 8, 1899, Coming to Their Squam Reservation; Gloucester Daily Times, Sept. 23, 1902, p. 2: Indian Encampment Broken (Sayward Street).

[15] An explanation of Algonquian terms for identity appears in the first pages of Steven F. Johnson’s Ninnuock (the People): the Algonkian People of New England (University of Michigan Press, 1995). Sources for Algonquian place names include William Bright’s Native American Place Names of the United States (2004, see especially pp. 32, 41, 554, and 571); R. Douglas-Lithgow’s Native American Place Names of Massachusetts and his Native American Place Names of New Hampshire and Maine (2000); the chapter on Geographical Names in H. L. Mencken’s classic The American Language (1921, available at Bartleby.com); John Huden’s chapter on Indian Place Names of New England in Volume 18 of Contributions from the New York Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (1962, available at Archive.org/); and J. Hammond Trumbull’s vintage work, The Composition of Indian Geographical Names, Illustrated from the Algonkin (1870, available at Gutenberg.org). Other sources of information about place names are in Lyle Campbell’s 1997 American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (see pp. 156-168), and in articles by William Tooker (1904), Myron Sleeper (1949), and in C. Lawrence Bond’s 3rd edition book (2000) on the subject. Merrill McLane’s 1998 Place Names of Old Sandy Bay is a local, though inaccurate, source.

[16] Personal Communication with Gloucester Archives, March 17, 2015; Roger Babson, 1923, The Old Roads of Cape Ann, p. 43. Annisquam residents apparently referred to Samp Porridge Hill erroneously as Sand Porridge Hill or Sam Porridge Hill.