Europeans in the Northeast had fundamental misunderstandings about Native American political systems. Few appreciated that the groups they encountered had long and rich histories carefully preserved in oral traditions and complex systems of governance. Those misunderstandings and general ignorance became embedded in common belief and practice. The “discoverers” simply transferred European concepts to the people they encountered—for example, imputing the existence of tribes and clans and nations with chiefs and sovereign territories.1 So pervasive was this invented reality that Indigenous Peoples themselves gradually adopted it. In reality, however, nothing could be further from the truth. The Western-Abenaki-speaking Algonquians of New England were not organized as tribes, did not have clans, and did not have chieftainships. They had strong ties to their ancestral homelands and sacred places but did not believe in sovereignty. The Earth did not belong to anyone. Rather, everyone and every thing belonged to the Earth. Their complex political systems were based on networks of kinship and alliance, respect and reciprocity.

Political Organization

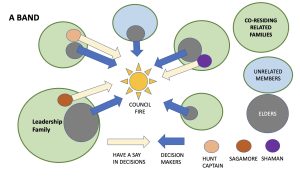

Pawtucket sagamores, sachems, and saunksquas were able members of high-ranking, or elite, families representing their patrilineage–their descent from a common male ancestor. They served as leaders of their band and stewards of their homeland. Eligibility for leadership was passed on within these families, fathers to sons and sometimes to daughters or leaders’ widows. A council of elders from the whole band chose the individual leaders from the eligible families by unanimous vote. Elected sagamores could then appoint their brothers, uncles, or nephews to assist them in their duties, or a saunksqua could enlist the aid of her sisters, aunts, or nieces as well as her male kin. Bands had homelands but moved freely throughout New England, which was a common territory.2 People could travel all around this common territory and be welcomed by every group that was not an enemy at the time.

The duties of a sagamore included allocating camp sites and resource procurement sites, hearing complaints and resolving disputes, directing conservation measures, conducting diplomacy with the leaders of other bands, collecting and paying and redistributing tribute, and overseeing community ceremonies and celebrations. Planning was done in conjunction with the counsel of elders and a shaman and other specialists as needed–for example, a captain of the hunt, a captain of a trading expedition, or a captain of a raid. Although a captain had to be obeyed to ensure the success of a particular mission, no one was compelled to obey a sagamore. Sagamores led by reputation, persuasion, and charisma. Members who did not agree could just do their own thing, come what may, or move to another band. Europeans, coming from societies with top-down authority structures, assumed disastrously that sagamores were chieftains who compelled obedience and therefore could be held responsible for everyone’s behavior!

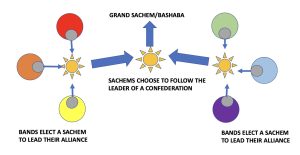

Beyond kinship, Algonquian political organization was built on fealty or allegiance to a sachem (saw kum), chosen by consensus or majority vote to lead a number of interrelated bands. Thus, the terms sachem and sagamore are not synonymous, as is often implied, nor is either term synonymous with chief. In European history a chief was the head of a clan or tribe. A lineage is not a clan, however, although both kin groups are based on the concept of a real or assumed common ancestor. Likewise, a band is not the same thing as a tribe. Bands are voluntarily cohabiting extended families with shifting composition and location, while tribes exist as corporate entities—independently of specific membership or residence—and occupy sovereign home territories. Furthermore, bands feature marriage rules requiring marriage outside of the band (exogamy), while clans tend to prefer members to marry within the clan (endogamy). 3 Sachems and saunksquas were responsible for establishing and maintaining alliances with other bands.

In other ways Algonquian and European political organizations of the time were similar. For example, peace pacts and military and trade alliances were cemented through marriage and maintained through diplomacy. On behalf of their client bands, sachems also sometimes allied themselves with or paid tribute to a grand sachem (whom Europeans referred to as a king or paramount chief), especially during times of threat or conflict. In the late 1500s, for example, the Penobscot established a Western Abenaki confederation against the Eastern Abenaki under a “grand sachem” named Bashaba. In the 1640s the Pawtucket of Agawam and Naumkeag, along with Nipmuc and Massachuset bands, joined the Pennacook Confederacy under Passaconaway.

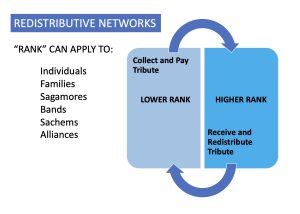

Every level of social organization, from family to confederation, operated on principles of rank, respect, and redistribution of resources (“wealth”). A family, a band, an alliance, and a confederation all acted as redistributive networks.

Social Stratification

Many old ideas about “primitive” or “tribal” people have been discredited, for example, the idea that early humans were matrilineal and worshipped goddesses and later evolved into patrilineal societies with gods. This idea emerged in the 1800s when European archaeologists first discovered sexually explicit Venus figurines in Paleolithic caves. The idea was further supported by the teleological philosophy of the times–that societies range in a divinely ordained natural progression from primitive/simple/matriarchal to modern/complex/ patriarchal. In reality, however, with a few exceptions, males have typically exercised more decision-making power and social control on a societal and intercultural level, and women on a familial and household level, regardless of the degree of social stratification or complexity of political organization.

At the same time, it is true that societies have tended to become more highly stratified when they have permanent settlements supported by agricultural surpluses, especially if they develop into states with urban centers. Stratification–the division of people into ranks, classes, or castes–arises in three main ways: 1) through hereditary or kinship status or family occupation; 2) through unequal allocations of land and resources or unequal redistributions of wealth; and 3) through conquest and coerced labor or enslavement. Pawtucket stratification was based on the first of these. Power passed from parents to offspring, was shared among kinsmen, and was brokered through marriages. Algonquian sagamores, sachems, saunksquas, shamans, elders, herbalists, healers, career warriors, gifted artisans, elite huntsmen, and middlemen and interpreters in trading networks were accorded greater prestige. But everyone worked.

As much as possible, “wealth” was redistributed evenly or held in common. In some Indigenous societies, the voluntary hosting of feasts was a means of redistribution. The community could consume, receive as gifts, or see destroyed the host family’s excess “wealth”. Economic anthropologists refer to this equalizing practice as a leveling mechanism–a means of correcting or mitigating economic disparities. A classic textbook example is the potlatch of the Kwakwaka’wakw [Kwakiutl] people of Northwest Coast.

Kinship

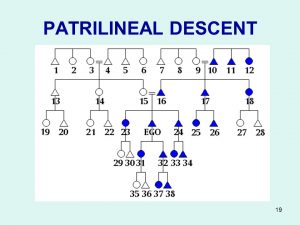

Algonquian political and social organization was based first on kinship. For the Pennacook and Pawtucket, kinship originally was patrilineal and patrilocal with preferential patrilaterial cross-cousin marriage and band exogamy. In other words, kinship was reckoned first through males. A bride retained her natal kinship status but became a member of her husband’s band and moved to make her home near the husband’s family. You ideally married a son or daughter of a paternal aunt (father’s sister) or the grandchildren of a paternal great aunt, who likewise were “cross-cousins” on your father’s side and therefore were defined as non-kin and eligible for marriage. You always married “out” of your band (exogamy).5

Patrilineal Descent (shown in blue)

The kin chart shows your patrilineage. Your band–the people you live with–would also include the wives and unmarried daughters of the males in your patrilineage, 3 or 4 generations of them, assuming they have not started bands of their own. Also in your band would be others not related to you who have been accepted or adopted into your group. Kidnapping and adopting people from enemy bands was a traditional means of replacing members killed in wartime and discouraging further conflict. If you are EGO in the diagram, your preferred marriage partner would be number 27, if you are male, and number 28 if you are female, as they are children of number 18, who is your father’s sister. A grandchild of number 12 would also be in your marriageable class. Numbers 23 through 26 are your sisters and brothers. Numbers 19 and 20 are cross-cousins on your mother’s side, while numbers 21 and 22 are parallel cousins on your mother’s side.

Your mother and mother’s sister you call “mother” and your father and father’s brother are both “father”—a form of classification called bifurcate merging. Meanwhile, your mother’s sister’s children and father’s brother’s children (parallel cousins) were classed as your sisters and brothers and thus were not eligible as your marriage partners. Confusingly, anthropologists refer to this type of classification system as “Iroquois Kinship” because of the way cousins are differentiated or classed with siblings. However, most Iroquoian-speaking peoples were and are matrilineal rather than patrilineal and organized as matrilineal clans rather than as affiliated patrilineal bands. Much later in their history, some Algonquians, including many Pennacook, were interned with Iroquoian-speaking peoples on reservations. They adopted matrilineal kinship, clan membership, and matrifocal tribal identity during the period of diaspora.6

Bifurcate Merging Kinship Terminology (Iroquois System)

In the diagram of bifurcate merging kinship classification, Mo stands for mother, Fa for father, FaZ for father’s sister, Mobr for mother’s brother, Br for brother, Z for sister, and CU for cross-cousin. Kin with symbols of the same color were called by the same kin term. The red square stands for “Ego”, the person reckoning his or her kin. Although the kinship classification system used by the Pawtucket and other Algonquians is called “Iroquois”, the people were not Iroquois linguistically or culturally beyond their shared adaptations as Eastern Woodland Indians.7

Across generations and marriages, bifurcate merging becomes more complicated. For example, you (as male ego) would refer to your daughter’s husband and your married sister’s son by the same kin term, but they would not be members of your kin group, nor members of your band. However, your daughter and your sister would always belong to your patrilineage. You would also use one kin term for both your son’s wife and your brother’s unmarried daughter, who would be coresiding with you in your band until such a time as your brother’s daughter married. Bifurcate merging kinship terminology had the effect of dividing a regional population into moieties, or halves, with each half eligible for marriage with the other. Thus, Algonquian social structure was not based on membership in a clan but in a marriage class called a moiety.8

Totemism

Lineages and moieties were identified with totems, sacred animal representations of the animal founders of lineages and the guardian spirits of kin groups. Algonquians traditionally believed that humans and animals are related–that some animals descended from humans, and vice versa. Deer, from example, are the progeny of a stag and a woman. Like deer and other animals, people are animals too. Indigenous people generally did not distinguish themselves from or regard themselves as superior to other animals.

Totemism is a belief system in which humans have mystical connections with animal ancestors or animals serving as guardian spirits. The word totem comes from the Algonquian word doodem.9 Traditionally, Abenaki totems included, for example, the turtle, beaver, bear, otter, and partridge. Other Algonquians included as totems the thunderbird, wolf, crane, loon, raccoon, fish, snake, and other animals, but the turtle and the bear were most common to all Algonquians, suggesting that these symbols may represent the original moieties of the founding population that first migrated to New England. The expression of totemism extended to individuals as well as to lineages. In a rite of passage linked with puberty, for example, boys went alone on a vision quest or spirit quest to receive guidance from the spirit world and to identify a personal totem that would serve as a lifelong guardian spirit.10

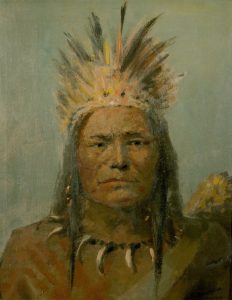

Colonial depictions of Indigenous peoples show body paint with totemic symbols. In a drawing by a French missionary (on the left), the snake and other marks on the Micmac hunter’s chest and arms represented his spirit animal and Eastern Abenaki kinship identification. John White’s 1585 watercolor of an Algonquian hunter at Roanoke, Virginia (on the right) faithfully records the body paint, dress, and accessories that identified the hunter’s lineage, totemic affiliation, and accomplishments.11

Algonquians did not make totem poles, but used totemic symbols in their art and painted symbols of their spirit animal on their bodies. Artistic representations also included petroglyphs carved on boulders, sculpted stone figurines, woven designs, and painted or carved symbols on objects of daily use. Ceremonial dances with costumes, masks, and props honoring kin group totems were a feature of Algonquian culture. Algonquian totems also were associated with character traits and social roles or occupational tasks. For example, members of the martens might be reputed as clever or strategic thinkers, while raccoon members might be renowned for curiosity or creativity. Members with a moose, elk, or beaver totem might be responsible for scouting, hunting, and gathering, while members with a fish, turtle, or snake totem might be responsible for teaching and healing. Bear and wolf members were warriors and defenders, and so on. In addition to sharing social roles within a band, because of exogamous marriage, individuals with the same totem retained a special bond independently of any particular band they belonged to. Such a kinship system is optimal for societies composed of small groups that depend on far-flung alliances for survival.

This figurine of a sitting bear in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA, is Pawtucket from the 16th Century and almost certainly represents the animal totem of one of the most prominent native lineages in New England.12 The black bear is the totem of Masconomet’s lineage, for example. Today, the flag of the Abenaki reservation of Odanak, Canada, where some descendants of the Cape Ann Pawtucket live today, includes the turtle, the black bear, and the thunderbird totemic symbols along with Canada’s national symbol of the maple leaf.13

Sagamores, Sachems, and Saunksquas

After kinship, which defined the role of sagamore, Pawtucket leadership was accomplished mainly through a family’s and an individual’s charisma, achievements, oratorical skill, and reputation. Leaders were empowered first through inherited family status and then through popular choice. They were chosen by a council of elders drawn from all the families in the band. Because Pawtucket leadership was both inherited and consensual, and because band exogamy led to networks of alliance, political organization remained fairly stable even as leadership changed. Higher status families and individuals exerted influence through status symbols, which included optional additional wives, greater wealth as reflected in quality of dress and furnishings, and superior location of residence or preferred resource procurement sites.14

The widows or daughters of sachems could lead in his place. They were saunksquas, often very powerful, whom Anglo-Europeans referred to as “queens” but omitted from their histories, assuming perforce that males were in change. Colonists referred to some powerful saunksquas as witches. Sachems, saunksquas, and sagamores paid tribute or received and redistributed tribute from member families or client bands. They often lived on fortified heights or on easily defended river islands. In pre-colonial times of threat, leaders in Greater Agawam governed from forts on hills or river islands in Newbury, Ipswich, Essex, Gloucester, Rockport, and Manchester-by-the-Sea that afforded good vantage points for detecting enemy raiders coming by sea.

Rock outcrops and high places had both secular and spiritual power. Hilltops, in addition to serving as lookouts and redoubts, also serve as ceremonial sites, astronomical observatories, and vision quest terrains. Some high mountaintops were viewed as places with the highest concentrations of manitou—the spiritual energy that inhabits people, trees, animals, rocks, weather, etc., and could work for good or evil. The Abenaki bmola (or pamola), for example, was a malevolent supernatural force (sometimes represented as a moose-headed bird) that lived on Mt. Katahdin in Maine and was responsible for cold winds and snowstorms.15

Mt. Washington in the White Mountains, the highest peak on the eastern seaboard, was regarded variously as a place of evil spirits or as the source of the Great Spirit’s manitou. It is said the Pennacook and Abenaki believed the mountain was therefore either too dangerous or too sacred to ascend beyond an altitude of 4,000 feet (1,220 meters). In 1636 an English colonist named Darby Field became the first European (and possibly even the first human) to climb Mt. Washington to its 6,288-foot (1,917-meter) summit.16

Caucuses

In addition to serving as watchtowers, defensive fortresses, sachems’ seats of power, sacred grounds, and the homes of powerful spirits, heights and hilltops also were places where special community gatherings took place, such as seasonal celebrations, powwows, and caucuses. Caucus is an Algonquian word for a meeting in which leaders or representatives of different families or bands debated and voted on policy, making decisions through consensus or by majority. Taking place on high ground, they literally were “summits” in the modern sense. Everyone who sat in the circle or “on the mat” had an equal say and could speak without fear of retribution. A speaker raised his or her hand to be recognized and finished speaking without interruption, providing an orderly procedure. This Indigenous decision making process was among leaders of autonomous groups who were acting in their own interests while also acting in the interest of their union, recognizing a higher central moral authority (a spiritual authority). This is a form of federalism, unknown in eighteenth-century Europe. The founders of the United States admired this model and adopted it in creating a nation out of a union of cooperating independent states.17

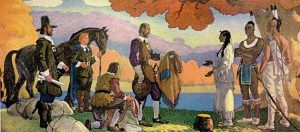

An Algonquian Caucus 18

In addition to sagamores and sachems, bands and tribes often had temporary leaders with complete authority for special purposes, such as pilgrimages to sacred sites, hunting parties, envoys to allies, and war parties. According to one Indigenous source (Sasichiminesh, personal correspondence 2019):

The truth is, we don’t have proper terms or proper and complete knowledge of political entities in this region. We don’t even have leadership terms properly sorted out: people use Sachem or Chief universally, but there are actually a number of official officer names, kinds of leaders (like ‘Chief’s men,’ Elders, Wise Ones, Ones Who Went Before, Herald, Chief’s Medicine Protector, etc., all of which have Indigenous terms specific to various nations). Moreover, I have uncovered new terms for paramount chief and mid-level chiefs from land documents that seem to have been overlooked and are not cited anywhere….In Lenape [the oldest Algonquian language], a sakima’s [sachem’s] herald is called “puchel.” There are terms from Indigenous persons for ‘headmen’ (lit. big persons) ‘leaders, big leaders’ (nikani, kitchinikani); tapauwauog (wise thinkers – Elders), which are akin to pauwauog (medicine persons), which are different from, but often include, nitskehuwaen (herbal healers); then there are mamontamak (diviners, petitioners), monetuak (fortunetellers, spell makers), and kosuquomak (sorcerers, black medicine makers). We also have Tannagak (Cranes) who are the vision dance Elders and the drummers in the Xingwikaon….Abenaki have their own specialized terms, and i’m not certain hierarchy is an appropriate way to categorize these terms. But, for example, kchisôgmô is a term for a paramount chief out of Abenaki at Odanak, such as Kchisôgmôak Masta and Sozap Lolo. Mdawlenno is the general term for medicine person in Western Abenaki.

So Algonquian political organization was more complex that we think and we have much more to learn. Another example comes from the Massachuset. In times of conflict, a war chief called a muggumquomp (Anglicized to mugwump) was chosen in a caucus or appointed by the sachem or grand sachem of a confederacy or alliance.19 A confederacy was formed as an intended permanent union, while alliances were formed for particular, more or less temporary, purposes. Mugwumps often had the power to make war independently of, and even in opposition to, their peace-declaring leaders. Conflict resolution strategies in which mugwumps and their retinues of “braves” campaigned against each other were intended to conduct warfare on the sidelines and thus preserve security and normalcy in civilian life for the rest of the population. An analog might be a cross between gladiatorial combat and cyberwarfare.

This breaking away of autonomous military authority was confusing to Europeans, who sometimes attacked peaceful villages and killed noncombatants on the assumption that they had authorized or abetted the depredations of mugwump-led raids. From mugwump we get a term first used in the 19th century for politicians who on principle break from their party on some issue.

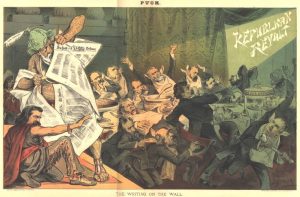

Political Cartoon 20

Like mugwumps behaving contrary to the wishes of their sachems, dissident Republicans were called mugwumps who bolted from their party in the 1884 U.S. presidential election over the issue of corruption. They supported the Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland instead of the Republican candidate James Blaine because of scandals associated with Blaine. (We may also see “mugwumps” in the 2024 presidential election.)

Shamans

In addition to sagamores, sachems, and temporary or special purpose leaders, men and women specializing in spiritual leadership and healing were powerful and essential members of Algonquian bands. Powah (powwaw, pawaw, powwow) is Algonquian for “shaman” and also for the public curing ceremony, purification ritual, or other rite performed or led by the shaman. By 1780 the English were using powwow as a verb meaning “to confer”, but powwaw literally means “one who has visions”.

In addition to communicating with the spirits through trance and meditation and channeling spiritual forces, shamans often had special knowledge of medicinal herbs and maintained extensive pharmacopeia. They cured illness, interpreted dreams, and recited oral traditions. They displayed dangerous skills, such as snakehandling, as a demonstration of their giftedness. They recognized omens and practiced divination (telling the future) and sorcery (magically changing the future). They supervised sweat lodge cleansings and conducted purification rituals to prevent evil spirits from entering individuals, wigwams, or villages (or to exorcise them). Shamans also watched the sun, moon, and stars; presided over a complex seasonal ceremonial calendar, and officiated at rights of passage such as birth, puberty, marriage, death, and burial. And Shamans served as key advisors to leaders.21

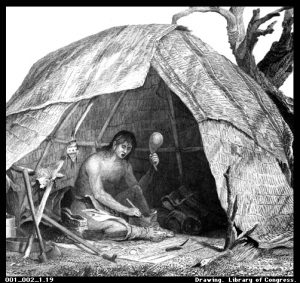

Colonial Depiction of an Algonquian Shaman 22

In this colonial depiction by an unknown artist, the shaman in his wigwam, surrounded by the tools of his trade, shakes a gourd rattle and chants while preparing a potion.

Pawtucket shamans practiced sorcery against their enemies: the Mohawks (Kanienkahaka) and the Tarrantines (Mi’Kmaq) and later the English or the French.23 Geopolitical concerns included the Iroquoians to the west, especially Mohawk, who wanted access to the Atlantic seaboard and later a monopoly on Dutch trade in the Connecticut Valley, and the Tarrantines to the east, who wanted corn, hostages to ransom, and revenge for whatever previous casualties they suffered in intergenerational warfare. Geopolitical concerns extended ultimately to the Europeans, who wanted the land and all it contained.24

Some Sachem and Sagamore Names

The Salem Registry of Deeds charts documented sagamores and sachems in Essex County and other counties in Massachusetts during the colonial period. Following are the names of some of the sachems and sagamores mentioned in this book and suggestions for how to pronounce them phonetically in English. Note that the syllable breaks are only for the convenience of English speakers and do not accurately reflect the real prefix-root noun-suffix structures of Algonquian words. For better or worse, diacritical marks have been left out. The names all represent French or English corruptions of the originals. Note that Algonquian pronunciation is almost never on the first syllable as it is in English.

Assacumbuit = Ass uh kumb wit (Maliseet “Tarrantine” leader)

Canonicus = Kan on ih kus (Sachem of the Narraganset)

Escumbuit = Es kumb wit (Pequaket Abenaki leader)

Kancamagus = Kang ah mayg us (Pennacook leader, nephew of Passaconaway)

Masconomet = Mask uhnom et (Masquenominet = Mask wenom i net, Sagamore of “Agawam”)

Madockawando = Muh dockoo and oh (Abenaki sachem of the Penobscot)

Membertou = Mem bear too (French: “Sagmaw” of the Mi’Kmaq)

Messamoet = Mes sah mo et (French: a Mi’Kmaq leader)

Metacomet = Meh tuhk om et (aka Pometacomit–King Philip, Wampanoag sagamore, second son of Massasoit)

Miantonomoh = Mee an toen om oh (also Mianonomi, leader of the Narraganset, nephew of Canonicus)

Nanepashemet = Na nah pash em et (Nipmuc leader of a Nipmuc-Massachuset Alliance)

Numphow = N umpf ow (Pennacook “sagamo” of Wamesit, uncle of Passaconaway)

Onamechin = O nah meech in (Abenaki sachem of the Sokoki-Saco Alliance)

Ousamequin = Oo sah meek win (aka the honorific title of Massasoit = Mas sah soy ut, sachem of the Wampanoag)

Quiouhamenek = Kwee oh hah men ek (“sagamo” of Wenesquawam [Cape Ann])

Passaconaway = Pas suh kohn nuh way (a corruption of Papisseconewa [Pa pis sa kon ew a, “Child of the Bear”], grand sachem of the Pennacook Confederacy)

Sassacus = Sa sak kuss (a corruption, often mispronounced Sas a kuss, sachem of the Pequot)

Uncas = Un kuss (sachem of the Mohegan)

Wonalancet = Wah nah lahn set (Pennacook sachem, son of Passaconaway)

Some saunksquas who played significant roles in King Philip’s War of 1675-1676:

Weetamoo (Pocasset Wampanoag)

Squaw Sachem (Natick Massachuset)

Awashonks (Sakonnet Narraganset)

Quaiapen (Niantic Narraganset)

Masconomet and Nanepashemet

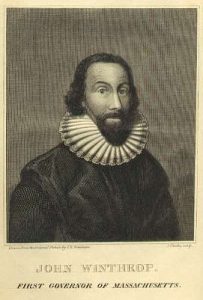

In 1630 the sagamore of Agawam, Masconomet (Masquenominet), famously met Governor John Winthrop (1587-1649) on the Arbella between Manchester Harbor and Beverly Harbor off Salem Sound (not in Salem Harbor as often erroneously reported). Winthrop was coming to replace John Endicott as governor of the newly formed Massachusetts Bay Colony. Endicott was with remnants of the Dorchester Company and new arrivals from England at Naumkeag (Beverly-Salem) at the time (and their story is forthcoming).

Winthrop promptly moved the capital from Salem Village to Dorchester and in 1634 sent his son, John Winthrop Jr. (1606-1676), to Agawam to evict squatters who had bought land directly from the Indians prior to the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Company and to found a plantation there (Ipswich). The goal was to prevent any designs the French might have on extending their influence further down the coast on the Gulf of Maine. Winthrop Jr. arrived with 11 men from Charlestown whose families would constitute the founding population and set about purchasing and appropriating Indigenous land and resources.25

Representations of Masconomet 26

In 1637, Winthrop Jr. paid Masconomet £20 for a quitclaim deed to some of the sagamore’s personal landholdings. This first deed specifies farmland along present-day Argilla Road between Labor-in-Vain Creek and Chebacco Creek, including Castle Hill and Sagamore Hill. Winthrop Jr. noted this sale in his papers, but did not occupy “Argilla Farm” or Sagamore Hill or Castle Hill on Plum Island Sound. He was intent instead on founding colonies in Connecticut. Later in 1638, Masconomet sold the entirety of “Agawam” (Salem Sound to the Merrimack River) to the Ipswich colonists for another £20. Winthrop Jr. sued in the Massachusetts General Court for reimbursement of the purchase price for the first deed and won. In 1644, after moving to New London, Connecticut, Winthrop Jr. deeded Castle Hill to his Deputy Governor and brother-in-law, Samuel Symonds. In 1910 the Crane family acquired the property, which is now managed by the Trustees of Reservations.27 Until recently, the locations of Agawam Village, Masconomet’s homestead on the Castle Neck River, and information about the place of the Pawtucket in local history have been suppressed, withheld from the pubic.

The First Deed Masconomet Signed

I Masconnomet, Sagamore of Agawam, do by these presents acknowledge to have received of Mr. John Winthrop the sum of £20, in full satisfaction of all the right, property, and claim I have, or ought to have, unto all the land, lying and being in the Bay of Agawam, alias Ipswich, being so called now by the English, as well as such land, as I formerly reserved unto my own use at Chebacco, as also all other land, belonging to me in these parts, Mr. Dummer’s farm excepted only; and I hereby relinquish all the right and interest I have unto all the havens, rivers, creeks, islands, huntings, and fishings, with all the woods, swamps, timber, and whatever else is, or may be, in or upon the said ground to me belonging: and I do hereby acknowledge to have received full satisfaction from the said John Winthrop for all former agreements, touching the premises and parts of them; and I do hereby bind myself to make good the aforesaid bargain and sale unto the said John Winthrop, his heirs and assigns for ever, and to secure him against the title and claim of all other Indians and natives whatsoever.

Witness my hand. 28th of June, 1638

Witness hereunto, John Joyliffe, John Downing, Thomas Coytimore, Robert Harding, Masconomet, His Mark

The next year for another £20 Masconomet deeded the rest of Agawam—most of Essex County–to Winthrop as well. Did Masconomet know what he was doing when he signed these deeds? Yes, and that’s another story, to come.28

As sagamore, Masquenominet was the hereditary head of a high-ranking family in his patrilineage. He was the authority figure for the macro-band of interrelated extended families occupying Essex County. He would have been responsible for allocating and redistributing subsistence areas to the families in the homeland, which is why he was the one signing the deeds, undoubtedly with the consent of other leaders. At the same time, Masquenominet paid tribute to other high-ranking sachems, including the leader of their alliance. During the Contact Period he paid tribute to the eldest son of the Massachuset sachem Nanepashemet (Sagamore James, Montowampate).

Masconomet welcomed Winthrop Jr. and encouraged the English to settle, first at defensive sites near the shore. He invited them, for example, to occupy his fort on Castle Island in Castle Neck River, Ipswich. In exchange for land he asked for protection against Pawtucket enemies. Accounts of the Massachusetts Bay Colony record how early settlers of Ipswich aided Masconomet against the Tarrantines, as Champlain had earlier aided the Pennacook and Abenaki against the Huron (Wyandot) and the Mohawk. According to a deposition of William Dixie of Ipswich, for example, given in 1629:

They [the “Agawame Indians”] inform Governor Endecott, that they are fearful of an invasion from the Tarrentines or Eastern Indians. He immediately despatches a boat with Hugh Brown and others, to defend them. Such aid was afforded them several times.29

Great Castle was on a spit of land extending into the Little Castle Neck River from Hog (Choate)Island. This was the site of one of Masconomet’s one forts in Agawam. 30 The other fort was on present-day Town Hill on the Ipswich River.

In addition to raiding for corn, the Tarrantines were seeking to avenge their dead from previous campaigns against them by Masconomet and his allies. In those campaigns the Pawtucket allies may have been seeking to avenge the death of their grand sachem Nanepashemet, killed by Tarrantines in Medford in 1619. Pawtucket sagamores had been clients of Nanepashemet (1575-1619), who led the Pawtucket, Nipmuc, and some Abenaki and Massachuset bands at the time of European contact. A daughter of Masquenominet, Joan, was married to Nanepashemet’s son Wonohaquaham (John), and after Nanepashemet’s death, Masquenominet paid tribute to Nanepashemet’s son Montowampate (James). After Sagamore James died in 1633, Masconomet paid tribute to Nanepashemet’s youngest son, Wenepoykin (George). Masquenominet (Anglicized to Masconomet or Masconomo means “Named for the black bear”), was a name bestowed on him as an honorific. Recall that the black bear was his totem. His given name was Quonopkonat, which remains untranslated.31 A new unconfirmed Indigenous genealogical database suggests that he may have been related to the Quanopowkhit family of Natick (related to Nanepashemet’s son George (Wenepoykin), and there is an unsubstantiated claim that Masconomet’s wife was a Wampanoag.

Masconomet’s name appears in all the following ways in the literature: Sagamore John, Indian John, Masquenominet, Masquenomoit, Mascanamenet, Machanomett, Maschanominet, Masconominet, Muskonominet, Muskonomett, Musconominet, Mascquenomet, Mascomonet, Masconomma, Masconnoma, Masconomo. In Mass. Bay Colony records he is known by his Christian name, John, following his conversion in 1640. I chose Masquenominet because that is his how his own descendants, who were literate, wrote his name. His children’s and grandchildren’s Christian surnames include Tyler and English and there are living descendants today.32

Masquenominet

Masque (Mask) = “the black bear”

nominet = “one named for”

Algonquians did not use personal pronouns such as he or she, but an English speaker would be tempted to say, “He is named for the black bear.”

After previous failed attempts on his life at his summer retreat on Marblehead Neck and elsewhere, Nanepashemet was finally killed in 1619 by a Tarrantine war party, most likely in retaliation for his support of the Saco of Maine in their attacks against the Tarrantines in earlier years. He was killed in his hidden and heavily fortified log fort on Rock Hill, Medford, north of the Mystic River in what is now the Middlesex Fells Reservation.33

Nanepashemet’s Summer Residence, Marblehead Neck

According to Edward Winslow’s 1621 account, in addition to a stockade of trees, Nanepashemet’s fortresses (Winslow also describes another at Naumkeag) included watchtowers, a trench moat with a ramp, scaffolds with ladders, and platforms with shelves to cache stones to throw to repel the enemy. Defenders included archers, slingshot throwers, spearers, and rock droppers.34

In the 1930s the Massachusetts Centennial Commission erected a small historic maker, now missing, along what is now the Mystic Valley Parkway:

Rock Hill—Site of Lodge and Lookout of Nanepashemit. Sachem of the Nipmuc Indians. Mystic, his stockaded village, was about half a mile to the westward near High and Grove streets, West Medford. He was killed in 1619 and succeeded by his widow, the Squaw Sachem.35

It is in the context of the chain of vengeance following Nanepashemet’s death that the Tarrantines attacked Masconomet at Agawam on August 8, 1631. Nanepashemet’s Christianized sons—John (Wonahaquaham), sagamore of Saugus, and James (Montowampate), sagamore of Chelsea, and their wives (daughters of Masconomet and Passaconaway respectively) and their entourage—were visiting Masconomet at Sagamore Hill in Ipswich at the time of the attack, near Castle Hill and Choate (Hog) Island in Essex Bay. According to the account:

The Tarrentines, to the number of 100, came in three canoes, and in the night assaulted the wigwam of the Sagamore of Agawam, slew seven men, and wounded Masconomet and his cousins John and James, and some others, whereof some died after, and rifled a wigwam of Mr. Craddock’s men, kept to catch sturgeon, took away their nets and biscuit.36

At that time, the Tarrantines also kidnapped Sagamore James’s wife, Wenuchus (or Wennunchus), a daughter of Passaconaway, who was later ransomed and returned.

The Bridal of Pennacook

James was married to Wenuchus in 1629, an event immortalized in a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892). Whittier named the bride Weetamoo (a historical figure from a different story) and the “Saugus Sachem” as Winnepurkit (misidentified as Sagamore George, the third Nanepashemet brother, rather than as James). The poet’s pastoral and elegiac lines reflect both the romanticism and the fatalism of mid-19th century views of Native Americans and their way of life. Here, for example, is an excerpt from Whittier’s “The Bridal of Pennacook”, Part I. The Merrimac:37

O child of that white-crested mountain whose springs

Gush forth in the shade of the cliff-eagle’s wings,

Down whose slopes to the lowlands thy wild waters shine,

Leaping gray walls of rock, flashing through the dwarf pine;

From that cloud-curtained cradle so cold and so lone,

From the arms of that wintry-locked mother of stone,

By hills hung with forests, through vales wide and free,

Thy mountain-born brightness glanced down to the sea.

No bridge arched thy waters save that where the trees

Stretched their long arms above thee and kissed in the breeze:

No sound save the lapse of the waves on thy shores,

The plunging of otters, the light dip of oars.

Green-tufted, oak-shaded, by Amoskeag’s fall

Thy twin Uncanoonucs rose stately and tall,

Thy Nashua meadows lay green and unshorn,

And the hills of Pentucket were tasselled with corn.

But thy Pennacook valley was fairer than these,

And greener its grasses and taller its trees,

Ere the sound of an axe in the forest had rung,

Or the mower his scythe in the meadows had swung.

In their sheltered repose looking out from the wood

The bark-builded wigwams of Pennacook stood;

There glided the corn-dance, the council-fire shone,

And against the red war-post the hatchet was thrown.

There the old smoked in silence their pipes, and the young

To the pike and the white-perch their baited lines flung;

There the boy shaped his arrows, and there the shy maid

Wove her many-hued baskets and bright wampum braid.

O Stream of the Mountains! if answer of thine

Could rise from thy waters to question of mine,

Methinks through the din of thy thronged banks a moan

Of sorrow would swell for the days which have gone.

Not for thee the dull jar of the loom and the wheel,

The gliding of shuttles, the ringing of steel;

But that old voice of waters, of bird and of breeze,

The dip of the wild-fowl, the rustling of trees.

“Squaw Sachem” was the name by which Nanepashemet’s widow was known. Her real name is lost, but she was not Ashawonks, the “squaw sachem” of the Rhode Island Sacconet band, with whom she is sometimes confused. After her husband’s death, Squaw Sachem married his personal physician, Webbacowet, a shaman (pawaw) of the Musketaquid of Concord, MA. She also formed a new political alliance with the powerful Pennacook shaman and sachem, Passaconaway. This alliance had been cemented through the marriage of her son James to Passaconaway’s daughter Wenuchus. 37

So it was that Masconomet, Squaw Sachem, and Nanepashemet’s heirs all became subordinates or clients of the Pennacook powwaw turned sachem, Passaconaway, who had previously been a subordinate of Nanepashemet. Passaconaway became a legendary leader, as Nanepashemet’s legacy lost its power through the three-part division of his territory among his three sons and through general discontent over having a woman for a sachem. Like Masconomet and Nanepashemet, Passaconaway counseled peace with the Europeans and survived the Contact Period in good standing.39

Squaw Sachem and Passaconaway

The sachem Passaconaway’s name, Pappiseconewa, meant “Child of the Bear”, referring to his kin group, making him a natural-born protector of his people, a role he reluctantly (but for a time successfully) undertook during the Colonial Period. Passaconaway is reported to have been nearly seven feet tall, a charismatic magician and healer who answered a call to political leadership. Before he became a grand sachem, Passaconaway was a noted pawab (witch or sorcerer) as well as a powwaw (shaman), a powerful combination.40 In his account of 1637, Thomas Morton describes “entertainments” in which Passaconaway “conjured” physical feats such as juggling, appearing to swim underwater an impossible distance, and making ice in summer—complete with obscuring smoke and loud claps, common distractors in a magician’s repertoire:

Papasiquineo [Passaconaway], that Sachem of Sagamore [sic], is a Powah of great estimation amongst all kind of savages there; he is at their revels (which is the time when a great company of savages meet from several parts of the country, in amity with their neighbors) has advanced his honor in his feats or juggling tricks…to the admiration of the spectators, whom he endeavored to persuade that he would go under water to the further side of a river too broad for any man to undertake with a breath, which thing he performed by swimming over, and deluding the company with casting a mist before their eyes that see him enter in and come out, but no part of the way he has been seen; likewise by our English, in the heat of all summer to make ice appear in a bowl of fair water; first, having the water set before him, he began his incantation according to their usual custom, and before the same has been ended a thick cloud has darkened the air and, on a sudden, a thunder clap has been heard that has amazed the natives; in an instant he has shown a firm piece of ice to float in the midst of the bowl in the presence of the vulgar people, which doubtless was done by the agility of Satan, his consort.41

In his account of 1639, William Wood also reports on Passaconaway’s reputation for magic or “miracles”:

The Indians report of one Passaconnaw, that hee can make the water burne, the rocks move, the trees dance, metamorphise himself into a flaming man. Hee will do more; for in winter, when there are no green leaves to be got, hee will burne an old one to ashes, and putting those into the water, produce a new green leaf, which you shall not only see, but substantially handle and carrie away; and make of a dead snake’s skin a living snake, both to be seen, felt and heard.42

Representations of Passaconaway: Shaman, Grand Sachem 43

The seat of Passaconaway’s confederacy was Penacook, New Hampshire, today a part of Concord, NH, but for a time in the mid-1600s he resided at Wamesit and Pawtucket Falls (Lowell) in winter and at Agawam (Ipswich) and Wenesquawam (Cape Ann) in summer. He very likely visited Gloucester Harbor, Riverview, and Annisquam. If so, the English colonists, newly arrived in 1638-1640 to settle Gloucester, did not remark upon seeing a giant chieftain striding through the salt marshes or groves of white pine. In fact, unlike the colonists in surrounding townships, the people of Gloster Plantation seem not to have remarked upon Native Americans at all, a mystery I explore in another context.44

James and Wenuchus were visiting Masconomet that day in 1631 when the Tarrantines raided and kidnapped the “bride of Pennacook”. She was ransomed by Abraham Shurd of Pemaquid, an English trader who served as intermediary, for ten beaver pelts and some wampum. Wenuchus was returned unharmed to her father Passaconaway, but the marriage so famously romanticized in Whittier’s poem may have come to an end when Sagamore James declined to travel to the White Mountains to retrieve her—allegedly in the belief that doing so (rather than her being brought to him) would publicly acknowledge Passaconaway’s superior power. The exact chronology of these events—whether the chiefly competition occurred before or after the Tarrantine attack and kidnapping—is not clear. However, the question soon became moot. Two years later both James and his brother John were dead, victims of the smallpox epidemic of 1633.45

Nanepashemet’s widow and her three young Christianized sons had attempted to take up leadership of the Pawtucket. Sagamore John (Wonohaquaham, 1600-1633) governed at Medford on the Mystic River in the south, with Sagamore James (Montowampate, 1609-1633) at Saugus River to the north, and Sagamore George (Wenepoykin, around age 4 with a regent, 1616-1684) at Salem (Naumkeag). Wenepoykin was later known to the colonists as George Rumney-Marsh, and later still as George No-Nose. When John and James died in the 1633 smallpox epidemic, English colonists (whose numbers also were reduced by smallpox) nursed and raised the surviving Indian children, mainly as servants. According to journal entries of Governor John Winthrop:

It [the epidemic] wrought much with them, that when their own people forsook them [because they themselves were too ill to care for ill relatives], yet the English came daily and ministered to them.”

Some of the English in the towns around the bay took the Indian children into their homes hoping to rescue them from the smallpox. Most died, Sagamore John’s son was one of the few to survive. He was taken care of by Mr. John Wilson, pastor of Boston.

February, 1634 – Such of the Indian Children as were left were taken by the English, most whereof did die of the pox soon after; three only remaining…. 46

Squaw Sachem’s youngest son, George, survived, his face disfigured by the disease, but later was captured in King Philip’s War in 1675 and sold as a slave to Barbados. He survived to return, miraculously, in 1684, only to die later the same year at his sister Abigail Yawata’s wigwam in Natick. For this is another true thing about history: Its events can be thrilling, uplifting, or horrifying and its people heroes, villains, or fools, but as a body of personal narratives, it is nothing if not sad.

In 1639 Squaw Sachem deeded Cambridge, Watertown, Newton, Arlington, Somerville, and Charlestown to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Then, in 1643 as violence against Native Americans increased, she and five other leaders–including Masquenominet of Agawam and Naumkeag, Cutchamakin of Cochichewick (Andover); Josias Chickataubut of Nonantum (grandson of Chickataubut, the late grand sachem of Neponset, also lost in the smallpox epidemic of 1633); Nashacowam of Nashua, NH, a Pennacook; and Wassamagin of Wachuset, a Nipmuc–took an oath of allegiance to Massachusetts Bay Colony and King Charles I of England in exchange for protection. Passaconaway, grand sachem of the Pennacook Confederation of Abenakis, and his sons followed suit the following year.

A historic marker on Route 3 at the Winchester-Arlington line, now missing, identified “Squaw Sachem’s Reservation”:

Squaw Sachem of the Nipmucs sold (1639) all her people’s land excepting “the ground west of the two great ponds, called the Misticke ponds, for the Indians to plant and hunt upon, and the weare [weir] above the ponds for the Indians to fish at.”47

Aiden Ripley’s 1924 Mural of Squaw Sachem and Her Two Older Sons 48

The Oath of 1644

In 1642 John Winthrop Jr. had disarmed Masquenominet’s band for fear of uprisings such as had occurred a few years earlier in the Pequot War in Connecticut. Masquenominet petitioned to have their guns returned and to be given English protection from the colonists as well as from the Tarrantines. Because of population loss through disease and the loss of independent means of subsistence through the sale of their land, Masquenominet’s people were moving away. Others sought to assimilate, converting to Christianity, adopting colonial dress, fencing their farms, raising cattle, and intermarrying with the colonists servants or their African slaves. (The Dutch had introduced slavery in North American in 1619 even before the arrival of the Mayflower.) Some Pawtucket indentured themselves to English families as servants for life or as apprentices in English trades or as seamen on English ships. Families who stayed faced increasing pressure from a rapid influx of English colonists, and they risked becoming wards of the state or dependent on the charity of the towns.

The protection that the sagamores and sachems sought came at a price. The oath that Squaw Sachem, Masquenominet, and the others signed in 1644 included a rider that required them to try to become Christians. Their answers to questions put to them were recorded by the Puritan cleric Richard Mather. According to an account in the Ipswich archives (similar to an account in Massachusetts Bay Colony records), dated March 8, 1644: 49

Besides four other Sagamores, Masconnomet puts himself, his subjects, and possessions under the protection and government of Massachusetts, and agrees to be instructed in the Christian religion. The following questions are submitted to these chiefs, who give the accompanying replies.

1st. Will you worship the only true God, who made heaven and earth, and not blaspheme?

Ans. “We do desire to reverence the God of the English and to speak well of Him, because we see He doth better to the English, than other gods do to others.”

2d. Will you cease from swearing falsely?

Ans. “We know not what swearing is.”

3d. Will you refrain from working on the Sabbath, especially within the bounds of Christian towns?

Ans. “It is easy to us, — we have not much to do any day, and we can well rest on that day.”

4th. Will you honor your parents and all your superiors?

Ans. “It is our custom to do so, — for inferiors to honor superiors.”

5th. Will you refrain from killing any man without just cause and just authority?

Ans. “This is good, and we desire so to do.”

6th. Will you deny yourselves fornication, adultery, incest, rape, sodomy, buggery, or bestiality?

Ans. “Though some of our people do these things occasionally, yet we count them naught and do not allow them.”

7th. Will you deny yourselves stealing?

Ans. “We say the same to this as to the 6th question.”

8th. Will you allow your children to learn to read the word of God, so that they may know God aright and worship him in his own way?

Ans. “We will allow this as opportunity will permit, and, as the English live among us, we desire so to do.”

9th. Will you refrain from idleness?

Ans. “We will.”

After Masconnomet and the other chiefs had thus answered, they present the Court with twenty-six fathoms of wampum. The Court, in return, order them five coats, two yards each, of red cloth, and a pot full of wine.

So, to seal the deal the signers paid 6,240 shell beads, roughly 624 colonial dollars in value, essentially buying protection by paying tribute. In turn each was given two yards of cloth and a pot of wine. The Puritan minister wrote home that a new age of spreading the Gospel among the Indians had begun, and the Native Americans no doubt went home with word that a new age had begun of living under the protection of English law.

In 1644 the General Court the general court voted to allocate 100 English pounds to build up Masquenominet’s fort on Castle Island. The fort was to receive the benefit of 150 tons of lumber from Nantucket, a garrison, artillery and a commander. But real security remained elusive. in 1650, for example, even after promise of English protection, Great Tom of Newbury–who had converted to Christianity and fenced his land to raise cattle, attended church and paid taxes–sold his farm and indentured himself, his children, and his heirs for all time to three settlers of that town: William Gerrish, Abraham Toppan, an Anthony Somerby.50

The Oath of 1644 was a test of religious faith based mainly on the Ten Commandments, the contents of which are sufficiently universal to be unsurprising to the Native Americans who answered to it. Most societies have similar definitions of right behavior. Deeper differences of understanding divided them, however, for Native American spiritualism was not based on the underlying idea that people are inherently base or wicked and need to be saved through good deeds or divine intervention.

John Winthop, John Winthrop Jr., and Richard Mather 51

During Masquenominet’s time the Pawtucket enjoyed largely peaceful relations with the people of Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1658 the town of Ipswich appreciatively deeded 6 acres of land to him. He died later the same year, and in 1665 the same land was granted to his widow. He is remembered today in local place names as Masconomet and through observances at his known burial site on Sagamore Hill in South Hamilton, which has come under the protection of Indigenous tradition keepers and the Essex County Greenbelt Association. Masconomet’s Christian western-style gravesite (Algonquians traditionally hid their burials from view) is marked by an inscribed headstone and maintained by caretakers. People visit this public site today to leave tokens of respect.52

Masconomet’s Burial Site at Sagamore Hill in South Hamilton

Masconomet had baptized his children and given them English names. It is Masconomet’s grandson, Sagamore Samuel English, who deeded Gloucester-Essex (10,000 acres) to its settlers for £7 on January 14, 1701. The payment was a final installment in cash for land that Gloucester had rented from the Native Americans of Cape Ann since 1642 in exchange for bushel baskets of Indian corn. The cash payment was ordered by the General Court of the Mass. Bay Colony, for Masconomet’s heirs had brought suit against Gloucester for unpaid back rent, and won.53

The need for “Agawam” to be re-deeded at the end of the 17th century, as explained in another context, stemmed from the fact that each township later carved out of that area needed clear legal title to its own bounded territory. Between 1686 and 1701 Samuel English and Masconomet’s other grandchildren also signed quitclaim deeds to Beverly, Boxford, Manchester, Rowley, Topsfield, and Wenham. Their grandfather’s decision to “sell” Agawam had occurred in the context of appropriations of land by the well-armed English founders of Ipswich, on the heels of a wave of catastrophic disease. Contributing factors also included the Iroquois and Tarrantine threats; the ongoing need for protection against both enemies and colonists, reflected in the Oath of 1644; and the complexities of post-Nanepashemet domestic politics under Passaconaway.54

Widowed a second time, Squaw Sachem retired first to Naumkeag with her youngest son Sagamore George, and then to Medford, where she died of old age in 1667 at a site that is now somewhere on the grounds of the Winchester Country Club. Her family, Christians all, was removed to the Praying Indian village of Natick. In 1675, her descendants at Natick were among the 500 or so Praying Indians interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor for the duration of King Philip’s War, where many died of exposure and starvation.55

It is debated whether Passaconaway ever converted to Christianity, as his sons did. In 1648 he invited the “Missionary to the Indians”, John Eliot, to Pawtucket Falls to preach to the Pennacook, Pawtucket, and Nipmuc. Eliot, and Daniel Gookin, Superintendent of Indians for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, were intent on creating a chain of Praying Indian villages on the English frontier for Christian converts. Indigenous wise men had noted that the Christian god seemed more powerful than the Great Spirit, as Passaconaway implies in his famous farewell speech, allegedly witnessed and recorded by one or more unidentified Englishmen at Pawtucket Falls in 1660. That year, having survived disease epidemics, Mohawk wars, misunderstandings in which he had to pay ransom to free his sons from English jails, and various hostilities by colonists and native enemies, Passaconaway abdicated his authority and leadership to his son Wonalancet. He died sometime between 1663 and 1669 at an unknown location in the White Mountains.56

Passaconaway’s Farewell Address

There is something about the rhetoric of farewell addresses and their forewarnings, sooner or later borne out, it seems. Passaconaway’s speech is in the genre of Eisenhower’s warning about the military industrial complex or MacArthur’s about the threat of Asian ascendancy. I’ve chosen the oldest and most authentic sounding version of the oratory I could find, although they no doubt are all melodramas based on hearsay.

Hearken to the words of your father. I am an old oak, that has withstood the storms of more than a hundred winters. Leaves and branches have been stripped from me by the winds and frosts, — my eyes are dim, — my limbs totter, — I must soon fall! But when young and sturdy, when my bow no young man of the Pennacook could bend, — when my arrows would pierce a deer at a hundred yards, and 1 could bury my hatchet in a sapling to the eye, — no wigwam had so many furs, no pole so many scalp-locks, as Passaconaway’s. Then I delighted in war. The whoop of the Pennacook was heard on the Mohawk, — and no voice so loud as Passaconaway’s. The scalps upon the pole of my wigwam told the story of Mohawk suffering. The oak will soon break before the whirlwind,—it shivers and shakes even now; soon its trunk will be prostrate, — the ant and the worm will sport upon it. Then think, my children, of what I say. I commune with the Great Spirit. He whispers to me now: “Tell your people, Peace — peace is the only hope of your race. I have given fire and thunder to the pale-faces for weapons,— I have made them plentier than the leaves of the forest; and still shall they increase. These meadows they shall turn with the plough, — these forests shall fall by the axe, — the pale-faces shall live upon your hunting-grounds, and make their villages upon your fishing-places.” The Great Spirit says this, and it must be so! We are few and powerless before them! We must bend before the storm! The wind blows hard! The old oak trembles, its branches are gone, its sap is frozen, it bends. It falls! Peace, peace, with the white man—is the command of the Great Spirit; and the wish, — the last wish—of Passaconaway.57

Wonalancet honored his father’s wish for peace, despite many provocations, but not his brother Kancamagus, who devoted his life to making war on the English.

Children in the colonial era were taught that the Indians’ Great Spirit was an avatar of Satan. Children today are taught that the Great Spirit is a version of the Christian God. How far from the truth are both these ideas? How—really—and how much did Algonquian perspectives on death and life and the sacred and the profane diverge from European perspectives? This is my next question.

Next: How Did the Pawtucket Make Sense of Their World?

Notes and References

- For example, see Ward H. Goodenough, Frontiers of Cultural Anthropology: Social Organization (1969), Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 113 (5): 329-335

- Principal primary sources of information on Algonquian social organization include the observations of the early explorers and the writings of John Eliot and Daniel Gookin. Principal secondary sources include classic ethnographic works, such as Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1907 Ancient Society, and Frank G. Speck’s ethnographic treatises on New England Indians, such as “The family hunting band as the basis of Algonkian social organization” (1915, American Anthropologist, 17: 289-305), and “’Abenaki clans’—Never!” (1935, American Anthropologist 37: 528-530). Speck was a summer resident of Riverview, Gloucester, between 1907 and 1950 and made many observations, interviews, and discoveries relating to the Native Americans of the Northeast. Another classic source is Anthony F. C. Wallace’s 1935 article, “Political Organization and Land Tenure among the Northeast Indians: 1600-1830”, in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 13: 301-321.

- The definitions and distinctions between tribes and bands (and chieftainships and states) were laid out by cultural anthropologists such as Elman Service (Primitive Social Organization, 1962) and Morton Fried (The Notion of Tribe, 1975), and are still debated, mainly because the term tribe is European in origin and has no analog in Algonquian languages. Algonquians referred to themselves simply as “the people (prefix Ninnu or Innu)” of a place, sometimes meaning “the original people” or “the real people” when differentiating themselves from other groups. See Steven F. Johnson’s 1995 book, Ninnuock: the Algonkian People of New England.

- The suggestions for name pronunciation are based on Frank Waabu O’Brien’s 2012 Guide to Historical Spellings and Sounds in New England Algonquian Languages (based on the research of colonial missionaries J. Eliot, J. Cotton, and R. Williams), published on the website of the Massachusett-Narragansett Revival Program of the Aquidneck Indian Council: http://www.bigorrin.org/waabu.htm. I chose this source over Abenaki language pronunciations, which are possibly more relevant but also more unfamiliar.

- These and the names of many other sagamores and sachems in Massachusetts at the time of European contact appear on the website of the Salem (MA) Registry of Deeds. See the Summary of Native American Deeds Collection at http://www.salemdeeds.com/nativeamericandeeds/indiandeedsummary_9-20-06.pdf. See also Sidney Perley’s 1912 The Indian Land Titles of Essex County, Massachusetts.

- Explanations of kinship classification systems were developed during the 1940s by cultural anthropologists such as George Peter Murdock in Social Structure (MacMillan, 1949). Through cross-cultural analyses, Murdock suggested that structural change in a society is a feedback loop that begins through a change in residence patterns (i.e., which relatives you live with or near after marriage), which changes how you relate to relatives, which changes how you think and feel about them, which in turn changes how you classify them linguistically. The Iroquoian classification system is one of only seven patterns occurring universally in human societies. Most European Americans use the so-called Eskimo system, in which siblings are differentiated from cousins and no distinction is made between cross cousins and parallel cousins. A convenient source of information on Kinship is the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (2008, Thomson Gale), available for free online at http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/kinship.aspx.

- The kinship diagram showing bifurcate merging comes from archnet@borealis.lib.uconn.edu, which is archived at http://archnet.asu.edu/archives/educat/anth220/kinship/iroquois.htm. For detailed information see George P. Murdock’s 1947 article, Bifurcate Merging: A Test of Five Theories,” American Anthropologist 49: 56–68, 1947.

- Totemism as practiced historically by the Algonquians of northeastern North America differs substantially from practices of totemism first described by anthropologists working in Africa, the Pacific Islands, and the Pacific Northwest, such as the classic Totemism by Claude Levi-Strauss, translated from the French by Rodney Needham, of which there are many editions. Totemism has been associated with clans and taboos, neither of which are central to Algonquian social structures or belief systems, which additionally exhibit great variability. See, for example, Sylvester Sieber’s Problems of Totemism Among the Northern, Northeastern, and North Atlantic Indians (University of Chicago Department of Anthropology, 1942) and Theresa M. Schenk’s 1997 article, The Algonquian totem and totemism: a distortion of the semantic field, in Papers of the Algonquian Conference 28: 341-353.

- For Algonquians of New England, totems were animal sisters and brothers who acted as spiritual helpers. In Abenaki mythology, humans were not differentiated from animals until the present day, the third age of mankind, and humans remain related to animals. The kinship connection was (is) felt as real.

- The totemic and other body paint symbols on the Mi’Kmaq hunter in Acadia, Cape Breton (in the image) was drawn by the French Jesuit missionary Abbé Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard, Apostle to the Mi’Kmaq in 1735. The totemic symbols on the Algonquian hunter in Virginia (in the 1587 painting by John White to the right) are pointed out in Lisa Heuvel’s 2010, Looking with Clearer Vision: The Significance of John White’s Watercolors, on the web site of the Jamestown and Yorktown Settlement & Victory Center: http://www.historyisfun.org/Significance-of-John-White.htm.

- For a true appreciation of the great number and variety of Algonquian spirit animals, see Chapter 10: Spirit Names and Religious Vocabulary by Dr. Frank Waabu O’Brien in the Algonquian Language Revival of the Aquidneck Indian Council at http://www.bigorrin.org/waabu10.htm.

- The Pawtucket figurine of a seated black bear, carved in soapstone, is in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA.

- The diaspora of Pawtucket, Pennacook and Abenaki to Odanak in the late 17th century is taken up in a later chapter. See the website of the Abenakis Band Council of Odanak at http://www.cbodanak.com/anglais/page_/accueil_agl.htm. The misappropriation and misuse of Native American totemic and other sacred symbols in non-Native entities and activities remains an issue today. For information on the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and Media, see the website of the American Indian Movement at http://www.aimovement.org/. In their histories, the fraternal orders with animal names (e.g., Moose, Elks), which began as men’s clubs in the mid- and late-19th century, do not acknowledge that their names derive from founders’ admiration of Native American totemic symbolism.

- For an appreciation of the complexity and fluidity of Algonquian social status and social mobility, see works by Elizabeth S. Chilton, for example, her chapter, Social complexity in New England: A.D. 1000—1600, in T. Pauketat and D. Loren, North American Archaeology (Blackwell, 2005): 138-160.

- Algonquian preference for high places or hilltops for special gatherings of people (and gods and spirits) is attested in many primary source accounts of Europeans observing in the 16th and 17th centuries, including Gosnold, Pring, Champlain, Smith, Wood, Lechford, Morton, Bradford, Winslow, Winthrop, and others. Classic sources on Abenaki mythology are Charles Leland’s 1884 The Algonquian Legends of New England, available at http://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/ne/al/ and also on archive.org, and Joseph Nicobar’s The Life and Traditions of the Red Man (1893). Read a good summary of Algonquian religious belief at the Multicultural Canada website, http://www.multiculturalcanada.ca/encyclopedia/a-z/a2/6. The concept of manitou and the subject of (Gitchi) Manitou are taken up in more detail in Chapter 7 of this book.

- The story of Darby Field is retold in Russell Lawson’s Passaconaway’s Realm (2002). The two Indians who overcame their fears to accompany Field to the summit of Mt. Washington may have been the first Native Americans in history to do so, but their names were not recorded.

- Sources on the influence of Native American governance on America, the new republic, are found in the writings of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Benjamin Rush. See, for example, A New Chapter, Images of native America in the writings of Franklin, Jefferson, and Paine, Chapter 8 in Donald Grinde and Bruce Johansen, Exemplar of Liberty, Native America and the Evolution of Democracy (1991).

- drawing of a caucus or council meeting “on the mat” was made by Joseph-François Lafitau, a French Jesuit missionary in Canada between 1711 and 1717. His ethnographic drawings from his book, Moeurs des sauvages ameriquains, are at the University of Cambridge in London and some may be seen on the web site of the Haddon Library. Notice the practice of raising one’s hand to be recognized to speak and the band of wampum on the mat.

- The etymology for mugwumps comes from The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition (Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

- The political cartoon, “The Writing on the Wall” by Joseph Keppler appeared on p. 199 of the June 18, 1884, issue of Puck and was reprinted on the Harper Weekly cartoon website: http:/elections/harpweek.com.

- Ethnographic sources on shamans include Frederick Johnson’s Notes on Micmac Shamanism, in Primitive Man 16 (3/4): 53-80 (1943) and Frank Speck’s many articles on the subject, such as Penobscot Tales and Religious Beliefs, in Journal of American Folklore 6:38-48 (1935), and Penobscot Transformer Tales, in the International Journal of American Linguistics 1: 187-244 (1918).

- The colonial depiction of a shaman is in the John Carter Brown Library, Archive of Early American Images and Maps Collection, Providence, RI: Brown University, and may be seen at http://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/JCVMAPS~1~1.

- Daniel Gookin, Thomas Morton, and other observers reported on natives practicing sorcery against the English, which is also attested in native texts, including Passaconaway’s farewell speech. Indians consequently were caught up in the witchcraft hysteria/delusion of the 1690s, as recorded by Cotton Mather in Robert Calef, The Witchcraft delusion in New England, Volume 3: More Wonders of the invisible World (1866).

- Principal sources on the geopolitics among Native Americans before and during European contact include primary source accounts, such as Champlain’s; David Stewart-Smith’s ethnographies; the Massachusetts Archive Collection, Volume 30: Indian, 1603-1705: Records detailing the interactions between the Massachusetts Bay government and native peoples in New England and New York; and articles by Erik S. Johnson: Community and Confederation: A Political Geography of Contact Period Southern New England, in The Archaeological Northeast: 156-168 (Levine, Nassaney, Sassaman, and Sassaman, 2000), and Embracing Ambiguity: Native Peoples and Christianity in Seventeenth-Century North America, in Ethnohistory 50 (2): 247-259 (2003).

- Accounts of Masconomet meeting John Winthrop in Beverly Harbor and the founding of Ipswich by John Winthop Jr. are given in Winthrop’s 1649 History of New England 1630-1649. The Babcock (1790), Savage (1853), and Hosmer (1908) editions of Winthrop’s history make for an interesting comparison. See also Joseph Felt’s definitive History of Ipswich, Essex, and Manchester (Clamshell Press, 1966). John Winthrop Jr.’s accounts are in The Winthrop Papers (Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 5).

- The mural representing Masconomet deeding Agawam to John Winthrop Jr., by Alan Pearsall, is painted on a building on Riverwalk in Ipswich, MA. The fictive 19th century portrait of the sagamore as an older man, by William Henry Tappan, hangs in the Trask House in Manchester-by-the-Sea, MA, headquarters of the Manchester Historical Society.

- The deeds signed by Masconomet are on the web site of the Salem (MA) Registry of Deeds. Castle Hill, the Crane Estate including Crane Beach and Castle Neck, and nearby islands, such as Choate (Hog/Hogg) Island, Long Island, Great Castle, and Castle Island, are private properties with restricted access managed by the Trustees of Reservations. See their web site at http://www.thetrustees.org/places-to-visit/northeast-ma/castle-hill-on-the-crane.html. Information on archaeological research conducted on these properties is not readily available to the general public or even to researchers. The Index to site reports at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, however, indicates extensive evidence of Native American habitation and use of these places from the Early Archaic Period through the Contact Period. Margo Davis’s Archaeological Potential of the Crane Reservations, Ipswich, Massachusetts (1996), which also is not readily available to the public, has been faulted by local historians such as Tom Beddall as incomplete or inaccurate (or possibly redacted). The Stone Science Library at Boston University has a copy of the Savulis et al.1979 Archaeological Survey of Ipswich, Massachusetts (MHC#25-246).

- A facsimile of this deed is on the web site of the Salem Registry of Deeds.

- Dixy’s first-hand account of John Endecott first aiding Masconomet against the Tarrantines is reprinted in Ronald Karr’s 1999 Indian New England 1524-1674: a compendium of eyewitness accounts of native American life. John Winthrop Jr. likewise aided Masconomet against the Tarrantines on more than one occasion, such that the Massachusetts General Court issued a cease and desist order against the sagamore to deter him from seeking further aid. See the accounts of John Winthrop and John Winthrop Jr. regarding Masconomet, also summarized in Joseph Felt’s history.

- The precise locations of Masconomet’s residences and principal forts, and his relocations after signing the Ipswich deeds are not well understood from existing and conflicting evidence. Popular local histories have Masconomet at Castle Hill or Sagamore Hill just behind it, with a move to Hog Island prior to retirement. However, Rufus Choate’s accounts of the 1890s in Echo place Masconomet’s residence south of Argilla Road on Fox Creek overlooking Essex Bay on land later owned by John Burnum Sr. and deeded to Jonathan Cogswell in 1703 (Essex Registry of Deeds, book 15, leaf 192). According to Tom Beddall’s research, Masconomet’s principal fort and watchtowers were not on Castle Hill but on islands in Castle Neck River (called Great Castle and Castle Island, within sight of both Fox Creek and Hog Island), as shown on the map.

- A well researched genealogical source is Ron Wiser’s web page on the descendants of Squaw Sachem and Nanepashemet at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~raymondfamily/wiser/WiserResearch.html. Compare this with Ellen Knight’s “Nanepashemet Family Tree” in the February 2006. Wiser Newsletter, Volume 11, Issue 2. Nanepashemet.pdf. Wiser identifies Quonopkonat as Masconomet’s given name and points out that he had to have been related to Nanepashemet through Nanepashemet’s wife Squaw Sachem, perhaps through marriage of her youngest son, sagamore George Wenepoykin of Nahumkeak (Salem area) to one of Masconomet’s daughters. Squaw Sachem’s sons, sagamores John, James, and George, most likely were Masconomet’s nephews-in-law, who would have been classified in their Iroquois kinship system as his brothers. They in any case visited him in Agawam and came to his aid against the Tarrantines.

- The various spellings of Masquenominet’s name are drawn from the first town histories of Essex and Middlesex counties as well as records of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Masquenominet is taken from the deed signings of his descendant Samuel English. The reconstruction and translation of Masquenominet is mine based on reconstructed Abenaki.

- For accounts of Nanepashemet in Marblehead see Chapter I of Samuel Roads’ 1880 History and Traditions of Marblehead, in archive.org. See also Joseph Felt’s histories. Primary sources include the accounts of the Naumkeag (Nahumkeake) Indians by Sir Ferdinando Gorges (Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, Volume 6) and by Francis Higginson (New Englands Plantation, or a Short and True Description of the Commodities and Discommodities of that Country (London, 1630).

- The chief source for Nanepashemet’s defenses against the Tarrantines in Salem, Marblehead, and Medford is Edward Winslow in William Bradford and Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s Relation, or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth (1622). See also Joseph Felt’s Historical sketch of forts on Salem Neck (Essex Institute 5: 255) and John Goff’s Remembering the Tarratines and Nanepashemet: Exploring 1605-1635 Tarratine War Sites in Eastern Massachusetts, in The New England Antiquities Research Association Journal 39: 2 (2008).

- The texts of the historical markers given in this book come from Historical Markers Erected by the Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentenary Commission (with texts revised by Samuel Eliot Morison), found at http://archive.org/details/historicalmarker00mass.

- Felt, History of Ipswich, Essex and Hamilton, p. 3. The story of the attack on Masconomet in Agawam in 1631 is told in all the local histories, based on the accounts and letters of John Winthrop, John Winthrop Jr., and other colonial observers.

- See The Squaw Sachem and Her Red Men, Chapter I of Henry Smith Chapman’s History of Winchester (1936). She is first mentioned in Book I of Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan (1637); an 1883 edition with notes by Charles Francis Adams is accessible at archive.org.

- The Bridal of Pennacook, Legends of New England, and The Garrison of Cape Ann are in Volume I of The Works of Whittier: Narrative and Legendary Poems, found online at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/9600.

- The alliance of Massachuset, Pawtucket, Nipmuck, and others under Passaconaway of the Pennacook Confederacy is described in Sanderson Beck’s New England Confederation 1643-1664 (2006): http://www.san.beck.org/11-5-Colonies1643-64.html#2 and is also recounted in Charles Edward Beals’ Passaconaway in the White Mountains (1916) and Russell Lawson’s Passaconaway’s Realm (2002). See also Pennacook Indian History on the Access Genealogy web site: http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native; Pietrowski’s 2002 The Indian Heritage of New Hampshire and Northern New England; the Encyclopedia of New Hampshire Indians: Tribes, Nations, Treaties of the Northeastern Woodlands by Donald Rickey (2000); and the works of David Stewart-Smith.