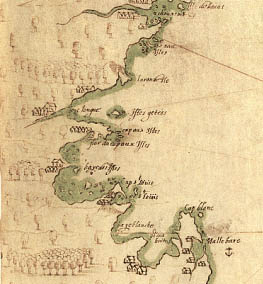

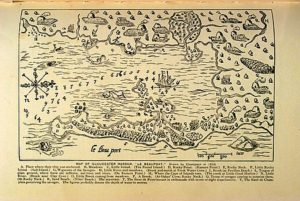

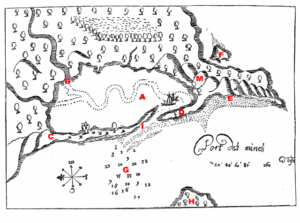

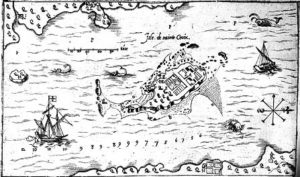

That the Pawtucket actually lived here is evidenced in Samuel de Champlain’s 1606 map of Gloucester Harbor (Le beau port) in what he called Cap aux Iles—“Islands Cape”. His map shows Pawtucket wigwams, gardens, and woodlots in parkland. The English later extended Native stages for drying fish on the southwest-facing slopes of the harbor where they first attempted to settle and built a fort (today known as Stage Fort).1

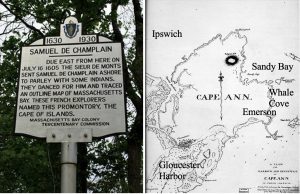

Champlain’s voyages to North America started in 1603, when he first served as a mapmaker on French expeditions, and ended with his death in Quebec, New France, in 1635. He sailed along the northern New England coast to Cape Ann in 1604 and came ashore here in 1605 and 1606. His accounts of meeting the Pawtucket in Whale Cove and Gloucester Harbor indicate friendly, though increasingly wary, encounters.2

The Pawtucket signaled Champlain’s barque from Emerson Point after it rounded the cape in 1605. The French were skirting the offshore islands, not sure where to go. The Pawtucket sent up smoke signals at Emerson Point, which the French saw. The intent was for them to come ashore closer to Sandy Bay, where evidence suggests an agricultural village was located. After some equivocation, they anchored eventually in Whale Cove when they got up the nerve to make contact. There was mutual ambivalence about making contact. Mariners had been attacked, and Indigenous people had been abducted. The Algonquians had already had Europeans on their coasts for a hundred years or more. William Shakespeare’s 16th century play Henry IV makes reference to “Indians” from Maine on display in Queen Elizabeth’s court. As a public entertainment they were made to paddle their canoes on the Thames.3

This is Whale Cove today, looking toward Straitsmouth Island. It’s on this expedition that the French gave the name Cap aux Iles, Islands Cape.

Adventures at Whale Cove

Sieur De Monts, the expedition leader, sent Champlain ashore to try to find out where they were. A whole train of navigators, explorers, merchantmen, and fishermen—some we’ve never heard of—had passed along the coast of New England prior to Champlain: Viking exiles, Diogo Ribeiro, Giovanni di Verrazano, Sebastian Caboto, Estévan Gomez, Jean Alfonse, André Thevet, John Hawkins, Bartholomew Gosnold, Martin Pring, George Weymouth, Henry Hudson, and John Smith, not to mention a host of nameless Basque and Breton entrepreneurs in the fishing industry. By all available evidence, however, Champlain was the first European ever to set foot on Cape Ann.4

Champlain’s map from Les Voyages shows Cap aux Iles and the coastline to the south that the Pawtucket obligingly drew for him. Champlain wrote in his diary:

We named this place Islands Cape, near which we saw a canoe containing five or six savages, who came out near our barque, and then went back and danced on the beach. Sieur de Monts sent me on shore to observe them, and to give each one of them a knife and some biscuit, which caused them to dance again better than before. This over, I made them understand, as well as I could, that I desired them to show me the course of the shore. After I had drawn with a crayon [chalk] the bay and the Islands Cape, where we were, with the same crayon they drew the outline of another bay, which they represented as very large; here they placed six pebbles at equal distances apart, giving me to understand by this that these signs represented as many chiefs and tribes.5

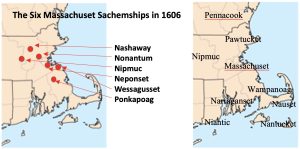

To Champlain’s sketch the Pawtucket had added the coast of Massachusetts Bay on the south side of Cape Ann, including Gloucester Harbor, Boston Harbor with all its Islands, and the shoreline as far Cape Cod. Then they placed six pebbles on the map to show the locations of the seats of the six powerful sachemships to their south in the Charles River drainage area. They also added the Merrimack River, which the French had not noticed because Plum Island blocks its entrance.6

The six Massachuset sachemships of the Charles River Valley included Weechaguskas (Wessagusset in Weymouth, near Quincy); Neponset (with Shawmut, near Canton); Ponkapoag (south of the Blue Hills in Milton and Dedham); Nonantum (Newton and Brookline), Nashaway (with Wachuset, around Leominster), and Nipmuc (Framingham to Worcester). These were Massachuset and Nipmuc groups. The Neponset and Ponkapoag later joined the Wampanoag further to the south, while the people at Nashua and Wachuset became more closely allied with the Pennacook to the north. The Pawtucket were friendly with the Nipmuc and the Massachuset.7

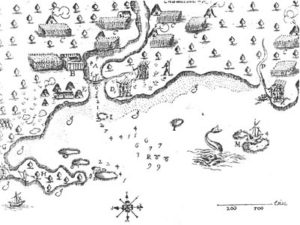

Armed with his new map, De Monts sailed away from Whale Cove and went to Boston Harbor. His ship’s log noted missing Gloucester Harbor that year because the wind and tide at the time favored keeping on their tack toward the south. Navigation on the rocky New England coast was truly treacherous in the age of sail. Champlain returned to Gloucester Harbor the following year under his own command with Sieur de Poutrincourt. He anchored his barque on the leaward side of Ten Pound Island and went ashore at Rocky Neck to make repairs to their shallop. His map of Gloucester Harbor identifies Ten Pound Island, where they anchored; Rocky Neck, where they repaired their shallop; and a creek nearby where they washed their clothes.8

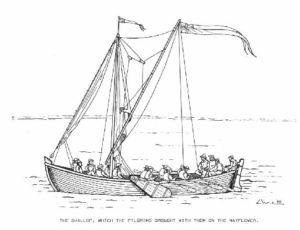

Shallop: From the French chaloupe, derived from the Dutch, sloep (sloop). The shallop was a heavy boat with both sails and oars and a shallow draft for navigating shallow waters, such as shoals and sand bars at river mouths. Variations on the shallop were indispensable for all the early explorers of the New England coast.9

Le Beau Port

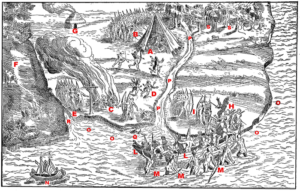

Champlain’s Map of Le Beau port (Gloucester Harbor) includes a key for identifying the lettered sites on the map. Here is my version of his key, based on three different translations from the French and combining my notes with those from other sources.10

A. Place where our barque was (Gloucester’s Western Harbor to the lee of Rocky Neck)

B. Meadows (Salt marshes)

C. Small island (Ten Pound Island); in the 1800s it was “forty rods long and thirty feet high with a lighthouse fifty feet above sea level” [a rod is 16.5 feet or 5.0292 meters]. Gloucester was sold for 7 pounds, not 10; Babson’s claim that the island’s name comes from an impoundment quota of ten rams is correct.)

D. Rocky cape (Brace Rock and Bemo Ledge)

E. Place where we had our shallop caulked. (Rocky Neck, with Native-made causeway)

F. Little rocky islet, very high on the coast. (Salt Island)

G. Cabins of the savages and where they till the soil (Wigwams of the Pawtucket)

H. Little river where there are meadows. (Brook with marsh flowing into Fresh-Water Cove beside Dolliver Neck)

I. Brook (Emptying beside Cressey Beach, not Pavilion Beach per one source)

L. Tongue of land covered with trees, including a large number of sassafras, walnut-trees, and vines (Eastern Point); in the 1800s it was three quarters of a mile long and about half a mile at its widest point, with a lighthouse sixty feet above sea level at the end to which Dogbar Breakwater was later added. Sassafras was a medicinal root in great demand in Europe as a cure for scurvy and siphilus. The cluster of rocks Champlain drew near L were later called Black Bess—possibly after the horse of Dick Turpin, an infamous 18th century outlaw who led the Essex Gang in England. In any case the name would not have been in reference to Queen Elizabeth.)

M. Arm of the sea on the other side of the Island Cape (The creek in the drowned marsh at Little Good Harbor Beach; probably not ‘Squam River flowing into Annisquam Harbor’, as another source suggests)

N. Small River (Brook near Clay Cove on the eastern branch of the inner harbor, today identified as Wonson’s Cove; another source says Cripple Cove nearby.)

O. Small brook coming from the meadows (Branch of the Little River, running through the Cherry Hill Marsh and the Train Bridge Marsh, joining the Annisquam near Gloucester Harbor above the Blynman Canal. Further to the north, Mill River and Jones River flow into the Annisquam River from opposite sides, which empties into Ipswich Bay.)

P. Another little brook where we did our washing (At Oakes’ Cove in the southwestern tip of Rocky Neck)

Q. Troop of savages coming to surprise us (On the eastern bank of Smith’s Cove, but Champlain probably misread their intentions.)

R. Sandy strand (Niles Beach; Interestingly, Champlain omitted Niles Pond and possibly did not see it or thought it was part of the ocean because of its unique proximity; the fresh water pond is separated from the sea only by a narrow natural dike that residents have reinforced over the generations.)

S. Sea-coast (Bass Rocks and the back shore along Atlantic Ave.)

T. Sieur de Poutrincourt in ambuscade with some seven or eight arquebusiers (Champlain’s detachment of marines)

V. Sieur de Champlain discovering the savages (Champlain’s caricature of himself freaking out, highlighting his sense of humor.)

Champlain’s map also shows our familiar harbor seals and a swordfish in what is now the head of the harbor! But we are left with so many questions! Why was Champlain here? What did he think of the Pawtucket and how and why did his views change? What kind of clothes were they wearing that they washed at Rocky Neck? And what’s all this about arquebusiers and an ambush?

Les Sauvages

In his first encounters with Native Americans, Champlain seems awe-struck and admiring. Though he called them sauvages, pronounced with a long a in the second syllable, a term synonymous with “primitives” or “pagans”), Champlain described the Indigenous people as tall—even some of their children were taller than the French—handsome, muscular, graceful, and playful. Champlain made drawings of the people he encountered, including the Pawtucket couple on Cape Ann (to the right in the panel below), including symbols of their practice of agriculture. The woman is holding an ear of corn and a summer squash. The man sports his hunting gear, turkey feathers, and a steel knife. The plant growing between them looks like Jerusalem Artichoke. Champlain wrote that of the foods he sampled, the tuber of a plant with yellow flowers was delicious and tasted like artichoke.11

Other drawings Champlain and his lawyer-artist shipmate, Marc Lescarbot, made show Algonquian men and women hunting and fishing and going to war. The legend for the illustration below on the left identifies what they wore when trading, traveling, and going to war. On the right are people in everyday wear, including women dancing at a harvest celebration, a woman on Cap aux Iles pounding dried corn in a log mortar, and a Saco fisherman in a basketry suit.12

Champlain also describes the plants and animals and the Algonquian’s corn plantations on cleared land; hillsides covered with currants and grapes; stands of hickory, beechnut, and walnut trees; feasts of passenger pigeons (which flocked in the millions and are now extinct); and useful communications with the natives of Cape Ann.

We saw some very fine grapes just ripe, Brazilian peas [beans], pumpkins, squashes, and very good roots, which the savages cultivate, having a taste similar to that of chards. They made us presents of some of these, in exchange for little trifles which we gave them. They had already finished their harvest. We saw two hundred savages in this very pleasant place; and there are here a large number of very fine walnut-trees, cypresses, sassafras, oaks, ashes, and beeches.13

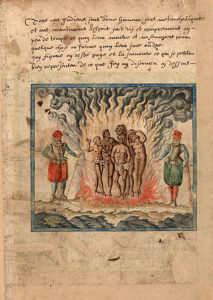

In his earlier career Champlain had witnessed and recorded Spanish atrocities in Santo Domingo, in which everyone who refused to convert to Christianity was burned alive. The experience shaped his resolve to inflict no harm on the Native people he encountered unless attacked.14

His later encounters with the Pawtucket, however, were fraught with misunderstandings and suspicions. Champlain’s map of Le Beauport immortalizes an incident in which he discovers a suspected Indian ambush and his lieutenant Poutrincourt and their arquebusiers (marines with front-loading, smooth-bore, matchlock guns) form a defense. What really happened, and why? We need to know more to answer this question, but based on their meddling in Native politics and mishaps on Cape Cod, the Frenchmen may not have been overreacting!

The “Ambush”

According to Champlain’s account:

The next day, as we were caulking our shallop, Sieur de Poutrincourt in the woods noticed a number of savages who were going, with the intention of doing us some mischief, to a little stream…at which our party were doing their washing. As I was walking along this neck, these savages noticed me; and, in order to put a good face upon it, since they saw that I had discovered them…they began to shout and dance, and then came towards me with their bows, arrows, quivers, and other arms…. I made a sign to them to dance again. This they did in a circle, putting all their arms in the middle. But they had hardly commenced, when they observed Sieur de Poutrincourt in the wood with eight musketeers, which frightened them. Yet they did not stop until they had finished their dance, when they withdrew in all directions, fearing lest some unpleasant turn might be served them….15

Detail of “Ambush” from Champlain’s Map

A central figure near “V” waving his arms is Champlain as he portrayed himself. The “savages” are shown dancing in a circle to the right, and the “musketeers” (arquebusiers) are in formation at “T” at the bottom of the inset.

The arquebus was a matchlock gun, a simple machine in which a burning wick was let down on an opened flash pan containing gunpower. The resulting flame ignited the charge in the barrel below. To be sure of having a flame to ignite the gunpowder when needed, arquebusiers often lit both ends of the wick, which risked burning up the wick prematurely and then not having a flame when you really needed it. This is how “burning your candle at both ends” came to mean dangerously overdoing things.16

The arquebus was a matchlock gun, a simple machine in which a burning wick was let down on an opened flash pan containing gunpower. The resulting flame ignited the charge in the barrel below. To be sure of having a flame to ignite the gunpowder when needed, arquebusiers often lit both ends of the wick, which risked burning up the wick prematurely and then not having a flame when you really needed it. This is how “burning your candle at both ends” came to mean dangerously overdoing things.16

What the Well-Dressed Arquebusier Wore in the first half of the 17th Century

Early arquebuses were too heavy to hold, load, and fire from the shoulder and had to be propped with a monopod. Later versions were lighter-weight muskets with various improvements to the firing mechanism.17 Imagine the Pawtucket hearing a round from an arquebus and watching the Frenchmen wash these clothes.

Under the auspices of Pierre de Mont and inspired by the exploits of the earlier French explorer, Jacques Cartier, Champlain was searching for a good site for the capitol of a French colony to be called New France. As a result of perceived Pawtucket hostility in the 1606 Rocky Neck “ambush” incident, he decided the Islands Cape was not the right place. Another reason was his observation that the Pawtucket were too preoccupied with fishing and farming to devote much time to hunting and trapping for furs, and that Cape Ann was somewhat scant in fur-bearing animals compared to Canada. The colony of New France was to be financed through the fur trade, making the hunting and foraging people to the north and along the St. Lawrence a more attractive prospect. The final deciding factor was that when not “planning ambushes” the Pawtucket seemed altogether too happy to see him. They wanted him to stay to receive more welcomers from Agawam, and they undoubtedly wanted the guns and knives and metal pots that the French were handing out to Pawtucket enemies to the north, especially the dreaded Tarrantines.18

It’s interesting to speculate what Gloucester would have been like as the capital of Henry IV’s or Louis XIII’s French-American colonial empire. As it happened, after considering Acadia and Port Royal in Nova Scotia, Cape Ann, and Cape Cod, Champlain and his patrons chose Quebec, founded as the capital of New France in 1608. In the Canadian Maritimes, French attempts at diplomacy exacerbated enmity among Indigenous Peoples at a time when they were not yet united against a common foe. An example is Champlain’s naïve interference in relations between the Micmac and their southern neighbors. In 1605 Messamouet, a Micmac (Mi’Kmaq) chieftain serving as a guide to the French in their quest to find a copper mine, and his lieutenant, Secoudon, traveled south with Champlain to Maine to visit Onemechin, a Saco (Choüacoet) sachem, and his second in command, Marchin. The goal was to enlist the Saco and their allies in the fur trade with the Micmac as middlemen. The French did not realize that an alliance between “Almouchiquois” and “Souriquois” would be impossible.19

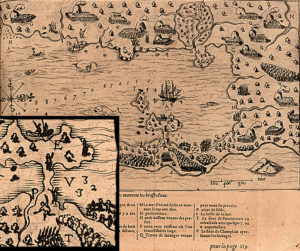

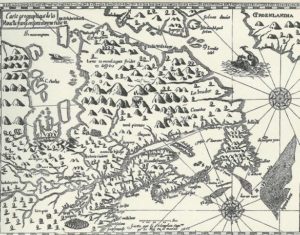

Messamouet led Champlain to the copper mine at E on this map of Port aux mines in Maine.

Meddling Cluelessly in Native Politics

The many names for Native Americans given by discoverers can be confusing when reading primary source documents. In general, the French called the hunter-gatherers of the St. Lawrence Valley the Montagnais (in the east) and the Algonquins (or Algonkins, in the west). Native Americans of the Canadian Maritimes and Nova Scotia, including the Micmac, they called the Souriquois (“agreeable people” in French), and the Abenaki people of the Maine coast, including the Penobscot, they called the Etchemins (“canoe men”). To the agricultural Algonquians of New England, including the Saco of southern Maine and the Pawtucket of Cape Ann, they gave the name Almouchiquois (or Armouchequois, meaning unknown). To the Algonquians, the Souriquois, and sometimes also the Etchemins, were their traditional mortal enemies, the Tarrantines.20

France’s “New World” in 1600

Ostensibly, the purpose of Champlain’s trip was to establish a Micmac-Saco alliance in aid of the fur trade, but the Saco were holding a Souriquois as a POW from a military campaign against the Micmac the previous year. Unbeknownst to Champlain, the POW was a relative of Messamouet. Messamouet paid a rich ransom for the return of his relative, which Champlain refers to as a gift exchange, but Onemechin perversely handed over the POW to Sieur de Poutrincourt instead of returning him to Messamouet. Onemechin also returned “lesser gifts”—filling a canoe with corn, squash and beans in exchange for higher-value steel knives and copper pots. Meanwhile, Poutrincourt assumed he was being given the POW as a personal slave. Messamouet was outraged and humiliated, leading to a series of wars that continued over the next 30 years.21

These wars pitted Mi’Kmak and others of the Canadian Maritimes, armed with guns, against coastal Algonquians to the south, armed with bows and arrows. Tarrantines (pronounced Tar ran teens) was not an ethnic or tribal name but might have been a corruption of 17th century French slang for “the terrorists” or “terrible ones”. They were coastal Souriquois and Etchemins of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and northern Maine, and may have included fierce Beothuk exiles from Newfoundland with whom they had intermarried. The French epithet “The Tarrantines” may have stuck through pure fame, much as the Mongols became “The Golden Horde”.22

According to Champlain’s account of the Micmac-Saco falling out between Messamouet and Onemechin:

Sieur de Poutrincourt secured a prisoner that Onemechin had, to whom Messamouët made presents of kettles, hatchets, knives, and other things. Onemechin reciprocated the same with Indian corn, squashes, and Brazilian beans [kidney beans]; which was not very satisfactory to Messamouët, who went away very ill-disposed towards them for not properly recognizing his presents, and with the intention of making war upon them in a short time. For these nations give only in exchange for something in return, except to those who have done them a special service, as by assisting them in their wars.23

Champlain did not connect this situation in Maine in 1605 to the Pawtucket “hostility” and suspected ambush he perceived in Gloucester Harbor in 1606. If there was hostility, it most likely was a direct consequence of the French role in Tarrantine aggression against the Saco in Maine the previous year in Messamoet’s revenge. The Saco were Pawtucket allies against the Tarrantines. The Tarrantines for generations had paddled down the coast from the north to make deadly raids on the agriculturalists of Casco Bay, Ipswich Bay, and Massachusetts Bay. Throughout the Northeast, raids and counter-raids were traditional and retaliatory. Other than getting revenge, Tarrantine goals were to steal corn, which would not grow well in the Maritimes or anywhere above the 50th parallel, to capture women, and to collect coups (scalps). In traditional warfare forces were evenly matched, attacks were low-tech and relied on surprise, and casualties were minimized to reduce retaliatory risks. Every death of a warrior killed in battle had to be avenged before the warrior’s spirit could ascend to the sky world. That all changed, however, when the Tarrantines got French trade goods. With iron kettles, steel knives, and guns, the value of corn and other crops as spoils of war decreased, warfare became far more deadly, and force of arms dictated outcomes.24

Taking Scalps

Traditionally, wearing a scalplock signaled manhood and warriorship. It was a long decorated hank of hair that your enemy would take, along with its patch of scalp, if he killed you in battle. Warriors counted and compared their coups, collected them on special poles, and decorated them and wore them as personal adornment. Collecting coups as an expression of a warrior culture later became a form of vengeful mutilation practiced on women and children as well as on male combatants and was practiced by the English colonists and militias against Indigenous people.25

Between 1605 and 1635 the Tarrantines devastated coastal populations, including the Saco in Maine, the Pawtucket on Cape Ann, and the Massachuset to the south. The northern raiders always had superior force, because the French were trading guns for furs at Tadoussac, the center of the fur trade on the St. Lawrence, down-river from Quebec. Champlain describes Tadoussac in 1603 in his Les Voyages. The trading post had been founded in 1600, with only 5 of 16 men surviving the first winter. Champlain’s trade alliances with the Hurons (Wendat), Abenaki, and Mi’Kmaq upset the balance of power in the Northeast, aggravating the Tarrantine Wars and also leading to warfare between the Pennacook-Pawtucket allies and the Iroquois.

The Pawtucket sagamore who met Champlain at Gloucester Harbor in 1606 was Quiouhamenec (pronounced Kwee oh ham en ek), who probably had just received the news of the French-abetted Tarrantine attack against their allies the Saco the previous year. Things started out well, but then Champlain reports an odd occurrence in which a Saco sachem (Onemechin on a surprise visit, no doubt arriving to confront Quiouhamenec about his dealings with Champlain), refuses Champlain’s gift of a jacket. Onemechin tries on the jacket, takes it off, puts it on, takes it off, indicating discomfort, and finally hands it over to a subordinate.

The chief of this place [Cape Ann] is named Quiouhamenec, who came to see us with a neighbor [cousin] of his, named Cohoüepech, whom we entertained sumptuously. Onemechin, chief of Choüacoet [Saco], came also to see us, to whom we gave a coat, which he, however, did not keep a long time, but made a present of it to another, since he was uneasy in it, and could not adapt himself to it.26

Here is what the Saco sachem may have meant (of which Champlain had not a clue):

“You aided our enemies and we are angry about it. We would retaliate, but you are involved with our ally the Pawtucket. I’m very uncomfortable with this conflict of interest. What can I do? If I refuse the jacket it means a declaration of war against you and my ally. If I accept the jacket it means the Saco accept defeat and subordination to the Pawtucket and the French. I hereby defer judgment by bestowing the gift on my subordinate.”

By neither accepting nor rejecting the gift, Onemechin creatively avoids the twin catastrophes. Champlain surmises only that savages are not used to wearing clothing. Whether or not this interpretation is correct, relations between the “Indians” and the Europeans undoubtedly were studded with many such communication errors and misunderstandings throughout the Contact Period. When Quiouhamenek asked Champlain to stay longer because 2,000 more people were coming to celebrate him (probably Pawtucket from Agawam), Champlain refused, writing in his journal that he couldn’t take a chance on being so outnumbered. Cross-cultural miscommunication is a whole field of study, and gift giving and reciprocity universally play important and complex roles in human relations. In any case, the alleged “ambush” incident at Rocky Neck happened the very next day, and Champlain sailed away, never to return.

In his memoirs Champlain gives no evidence of having understood his role or the role of the French fur trade in the ensuing conflicts among Indigenous Peoples. In 1607 Onemechin and his lieutenants and a hundred warriors were killed in an attack led by the famous Micmac chieftain Membertou, and in 1608 Quiohamanek and his lieutenants and many warriors were killed during their attempted retaliation against Membertou and the Tarrantines.27

In his memoirs Champlain gives no evidence of having understood his role or the role of the French fur trade in the ensuing conflicts among Indigenous Peoples. In 1607 Onemechin and his lieutenants and a hundred warriors were killed in an attack led by the famous Micmac chieftain Membertou, and in 1608 Quiohamanek and his lieutenants and many warriors were killed during their attempted retaliation against Membertou and the Tarrantines.27

Nevertheless, Champlain had put Le Beau Port on the map of northeastern North America. By 1612 Le Beauport appeared on French maps. Two years later Captain John Smith bestowed the moniker Cape Tragabigzanda, after the name of the Greek slave to whom he was gifted as a POW during an earlier misadventure in Turkey. This extravagant label appeared briefly on English maps when Charles I, heir to the English throne, renamed it Capa Anna after his mother.28

Cartographer Extraordinaire

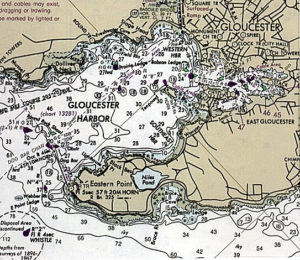

Champlain’s maps are surprisingly accurate for his day. He drew profiles of landforms to help mariners recognize coastlines as seen when approaching from the sea. He adapted his tools for ocean navigation (the quadrant and the astrolabe—simple machines) for use on land, and he had his men pace out distances as they walked the Cape Ann shoreline. Their unit of measure on land was the toise, equal to 1.94 meters or 6.4 feet. They plumbed harbor depths in fathoms. In the 17th century one French fathom was approximately 5.5 feet (or alternatively the arm span of the tallest sailor on board—to ensure a generous measure of depth in unknown waters). One English fathom was 6 feet, today’s international standard. Champlain’s harbor depths in French fathoms show that his ship—a small, three-masted, ocean-going 80-ton barque with a 35-foot keel, 14-foot breadth, and 6-foot hold—was anchored at Rocky Neck in only around 24 feet of water at mean tide. Oddly, with all the transformations the harbor has seen, the depth there is roughly the same today.29

Replica of the Don de Dieu (“Gift of God”) during the 300th anniversary of the founding of Quebec City in 1908. The barque that Champlain sailed into Gloucester Harbor in 1606 was a different ship of the same size and design.

Replica of the Don de Dieu (“Gift of God”) during the 300th anniversary of the founding of Quebec City in 1908. The barque that Champlain sailed into Gloucester Harbor in 1606 was a different ship of the same size and design.

Nautical Map of Present-Day Gloucester Harbor

Throughout his tenure in New France, Champlain mapped every coastal settlement, river mouth, and harbor he came upon, including distances and depths in fathoms. He also drew illustrations of events he saw, such as celebrations, parleys, and battles. His shipmate Marc Lescarbot and the Jesuit missionaries who accompanied the explorers to New France also drew explanatory maps and illustrations. Comparing and interpreting such a wealth of visual evidence has proven a wonderful challenge.30

Champlain’s map of the St. Lawrence River system and the Maritimes, for example, shows wigwams as hills representing Native American settlements of different sizes.

Champlain’s route to the Massachusetts coast took him from Port Royal in Nova Scotia, past Acadia toward Casco Bay. He stopped in Penobscot harbor and made this map. There is Indian Island in the river, showing the layout of the Penobscot village in Old Town, Maine, at that time.

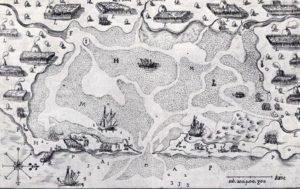

His map of the estuary of the Saco River in Maine shows the Abenaki corn plantations and flake yards of Onemechin’s people, and some warriors, as well as a grampus (a kind of North Atlantic porpoise) and a whale in the bay.

Champlain’s Map of the Saco River Estuary

Champlain’s Map of the Saco River Estuary

Champlain’s map of Plymouth harbor more than a decade before the English pilgrims came in the Mayflower shows the characteristic Native corn plantations, plus a powwow in progress on a spit of land at the mouth of the harbor. The friendship that William Bradford’s party enjoyed initially was extended though exceptional individuals, such as Samoset (a visiting Abenaki), Squanto (Tisquantum, an escaped Patuxet ex-slave), and of course the Wampanoag leader Massasoit. In general, however, the Wampanoags at Plymouth and the Nauset on Cape Cod did not maintain friendship to the English Pilgrims because of prior negative experiences with Champlain and the French mariners.31

Edward Winslow’s Copy of Champlain’s Map of Plymouth Harbor

Those prior experiences included murder and mayhem. Champlain gave Nauset Harbor the name of Malle Barre (Bad Bar) because of its shallow access afforded by a sandbar at the harbor entrance and perhaps also because one of his men was killed there by the Nauset when he attempted to prevent what he saw as a theft—at “B” on Champlain’s map (foreground to the right). The cook was washing pots in a stream when a “sauvage” took one. This conflict may have stemmed from mutual ignorance of cultural values regarding private vs. communal property and theft vs. borrowing. Despite this encounter, between 1620 and 1675, around 500 Nauset cohabited with the English at this site.32

Champlain’s Map of Nauset Harbor

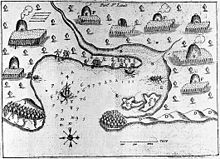

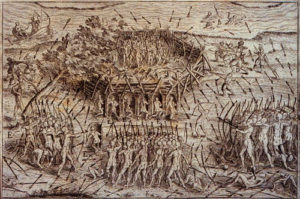

Champlain’s map keys often described specific events at the harbors he drew. For example here is a map of Stage Harbor in Chatham, or Monomoit, which Champlain called Port Misfortune. It traces an event in 1606 after leaving Cape Ann that contributed to Champlain’s decision to take Cape Cod, as well as Cape Ann, out of the running for the capital of New France. Here the French put ashore to explore and some men are left behind to bake bread. People who later became known as the Wampanoag attacked by surprise. They had gotten word of events at Mallebarre. There at Nauset the French had killed some “Indians” as a result of a misunderstanding over a copper pot that had left one Frenchman dead.

At Chatham the warriors at Monomoit killed a few of the men on kitchen duty and burned the bodies beside the Christian cross the French had erected, which the Wampanoag tore down and broke. We see survivors fleeing, stuck with arrows, and they are briefly defended by Native converts, guides and interpreters who had accompanied Champlain. The French come to the rescue in a shallop that is beseiged by the Indians as it nears shore. The Indians are beaten back but not before more Frenchmen fall and die in the harbor. Sieur de Poitrincourt arrives in his boat to pick up the pieces, after which the French make sail. They follow the coast southward, stopping at Providence, Martha’s Vineyard, and Narragansett, then rounding Nantucket to sail home to France, never again to return to New England.33

Returning to Canada in 1608 to continue his explorations, Champlain dutifully illustrated the battles in which he aided the Almouchiquois (the agricultural Algonquians of southern New England) against their western enemy, the Mohawks or Kanien’kehaka (Maqui, or “Maneaters” to the Almouchiquois), members of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. While the Almouchiquois’ eastern enemies the Tarrantines wanted corn, their western enemies the Iroquois wanted access to the Dutch fur trade in the Connecticut Valley, a greater share in the lucrative French fur trade on the coast, and access to wampum shells on the Atlantic beaches. In these battles as few as three or four musketeers turned the tide against the Iroquois. The Iroquois later avenged these attacks with devastating defeats for the Pawtucket, Pennacook, Nipmuck, Mahican, Sokoki, Missisquoi, and other New Englanders, in a series of wars, called the Beaver Wars, lasting until 1650.34

Here is Champlain in the center of this battle scene. He’s firing his arquebus at Mohawk warriors, who are shooting arrows at him in their first experience with guns in a joint Algonquian-French raid against the Mohawks. This took place in 1609 on the shores of what became Lake Champlain. No actual portrait of Champlain exists, but some of his maps may include “Where’s Waldo”-style self-portraits such as this one.35

Now we can answer the question that opens this chapter. All of Champlain’s maps from Quebec to Cape Cod show that he saw heavily populated harbors and river mouths. They prove without a doubt that Indigenous people in considerable numbers (between 200 and 2,000 at any one site) were living in coastal and interior New England prior to colonial settlement, and from southern Maine southward they were practicing agriculture. Now a new question: Who else came here before the Friendship landed Dorchester Company fishermen at Gloucester’s Fishermen’s Field in 1623, and what did they see?

Next: Who Else Explored Here and What Did They Find?

Notes and References

1. Of the translations of Champlain’s diary and account in Voyages, I relied most on the original 1878 translation by Charles Pomeroy Otis: Memoir of Samuel de Champlain, Volume II, 1604-1610, especially for his descriptions of Le Beauport and encounters with the Indians. See http://canadachannel.ca/HCO/index.php/Champlain’s_Voyages/. See also Langdon and Ganong’s 1922 edition of The Works of Samuel de Champlain, published by the Champlain Society (www.champlainsociety.ca ), and Henry Biggar’s six volumes, The Works of Samuel de Champlain, prepared between 1922 and 1936 and reprinted in 1971 by the Toronto University Press. In these editions, Champlain writes volume 1 in 1599, volume II in 1603, volume III in 1613, and the last three volumes in 1632. The original of Champlain’s map of Gloucester Harbor is in the Archive of Early American Images and Maps Collection at the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, RI, and versions of it can be readily found in Google Images.

2. Champlain anchored in what would become Boston Harbor but did not go ashore there. He sailed to Plymouth Harbor, then skipped Cape Cod Bay entirely and ended his New England landings at Nauset Beach. The map shows seven of his voyages of discovery between 1603 and 1624. See the Prince Society 1878 edition of Otis’s translation of Volume I of Voyages, edited by Edmund Slafter (http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/6653 and http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-115/index.asp ), which includes maps and illustrations. An accessible French source is Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l’an 1603 (“Concerning the Savages: or travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouages, made in New France in the year 1603”), which describes Champlain’s first voyage to Canada as the guest of François Gravé du Pont, who was in search of the Northwest Passage.

3. The stories of Epenow and other Indigenous abductees from the Northeast coast are told in another context.

4. Other voyages of discovery to New England and the Northeast are the subject of the next chapter.

5. From Part IX of Volume II of the Otis edition of Champlain’s Voyages.

6. The same six chiefdoms of the Massachuset were later identified in other contexts by Edward Winslow (Mourt’s Relation 1622), Thomas Morton (New English Canaan 1632), Roger Williams (A Key into the Language of America 1643), Samuel Maverick (A Briefe Description of New England 1660), and Daniel Gookin (Historical Collections of the Indians of New England 1674). These are all available online.

7. The principal primary source for the ethnography of the Indigenous people of New England, other than the first governors of the first colonies, is Daniel Gookin, the first Indian agent of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. See his 1674 account (Published in 1692, reprinted in 1792 and 1806), Historical collections of the Indians of New England and their several nations, numbers, customs, manners, religion, and government before the English planted there (Massachusetts Historical Society Collections): http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/sc_pubs/13/ . See also the early historian William Hubbard’s 1801 work, A Narrative of the Indian Wars in New England 1607-1677 (Greenleaf) and Wendell Hadlock’s 1947 article, War among the northeastern Woodland Indians, American Anthropologist 49 (2).

8. Biographies of Champlain I consulted included Samuel Eliot Morison’s 1972 classic, Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France (Little Brown) available at http://www.jstor.org/pss/1918378 and David Fischer’s 2008 tome, Champlain’s Dream (Simon & Schuster), although I found the latter too hagiographic to my taste.

9. For information on shallops, pinnaces, and other types of colonial and early American vessels, see, for example, Howard Chapelle’s 1951 article and others in American Small Sailing Craft: Their Design, Development, and Construction (W. W. Norton). The 2006 illustration of a shallop under sail is by Duane A. Cline.

10. The interpretation of Champlain’s map key in this book is my own. Interpretations by editors of Champlain’s Voyages tend to suffer from unfamiliarity with Gloucester’s landmarks. A more accurate local interpretation is offered in Marshall Saville’s 1934 Champlain and His Landings at Cape Ann, 1605, 1606 (American Antiquarian Society). There is a copy in Rockport at the Sandy Bay Historical Society, which Saville founded to house his collection of Native American artifacts found on Cape Ann. Another intimate source, The Fishermen’s Own Book, published in Gloucester in 1882, offers the following interpretation Champlain’s Le Beau Port map key:

A, The place where our bark was anchored. B, Meadows. C, Little Island. (Ten Pound Island.) D, Rocky Point. (Eastern Point.) E, The place where we caulked our boat. (Rocky Neck.) F, Little Rocky Island.(Salt Island.) G, Wigwams of the savages, where they cultivate the earth. H, Little river, where there are meadows. (Brook and marsh at Fresh Water Cove.) I, Brook. (Brook which enters the sea at Pavilion Beach.) L, Tongue of plain ground, where there are saffrons, nut-trees and vines.(On Eastern Point.) M, The salt water from a place where the Cape of Islands turns. (The creek in the marsh at little good harbor.) N, Little river. (Brook near Clay Cove.) O, Little Brook coming from meadows. (This brook cannot now be exactly located.) P, A little brook where they washed their linen. (At Oakes’ Cove, Rocky Neck.) Q, Troop of savages coming to surprise them. (At Rocky Neck.) R, Sand beach. (Niles’ Beach, at Eastern Point.) S, The sea-coast. (Back side of Eastern Point.) T, The Sieur de Poutrincourt in ambuscade with seven or eight arquebusiers. V, The Sieur de Champlain perceiving the savages.

11. Champlain’s sketches of Indians along with his descriptive keys may be seen at http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/franco_ontarian/contacts.aspx from Volume 4 of G. -E. Desbarats’ 1870 work, Oeuvres de Champlain (2nd ed., Archives of Ontario Library), facing page 81.

12. See Marc Lescarbot. 1606 (2013). Nova Francia: A Description of Acadia, 1606. New York: Routledge.

13. From Part XIII of Otis’s translation of Champlain’s Voyages.

14. Champlain’s observations of Spanish colonialism in the 16th century are in Slafter, Rev. Edmund F. 1878. Voyages of Samuel de Champlain, Volume I: 1567-1635.

15. From Part VII of Volume II of the Otis edition of Champlain’s Voyages.

16. See an online video of the matchlock firing mechanism, From Matchlock to Flintlock, by the Jamestown Settlement and Yorktown Victory Center in Williamsburg, VA: http://historyisfun.org/from-matchlock-to-flintlock.htm . See also an expert’s blog on

Sellswords, mercenaries, and condotierri, They Shot at the Skies: Soldiers and Firearms of 16th Century at http://sellsword.wordpress.com/2011/08/09/firearms/ .

17. An authoritative source on early firearms is Charles Black’s translation of Auguste Demmin’s 1877 An illustrated history of arms and armour (a free read in Google Books). The 1633 illustration of “mosquetero, piquero, and arcabucero” attire is in the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library.

18. Events surrounding Champlain’s departure from Cape Ann are described in Part XIII of Volume II of Otis’s translation of Champlain’s Voyages. In a letter to his monarch, also in Voyages, Champlain cites unpredictable natives and relative scarcity of fur-bearing animals as his reasons for seeking elsewhere to plant New France. A historical marker near the entrance to Gloucester’s Rocky Neck commemorates his visit to Le beau port.

19. Champlain describes the quest for American copper mines in Part III of the Prince Society edition of Voyages. Sources of metals and minerals, along with an abundant supply of furs, dictated the location of a capital for New France and at the same time muddied inter-tribal relations among Indigenous Peoples. Sources on the French fur trade and its impacts on Native Americans of North America include Dean Snow’s 1976 article, The Abenaki fur trade in the sixteenth century in The Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 6 (1); Colin Calloway’s 1991 Dawnland Encounters: Indians and Europeans in northern New England; Robert Grumet’s 1995 Historic contact: Indian People and Colonists in Today’s Northeastern United States in the Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries; and Thomas Nixon’s 2011dissertation, The North American Fur Trade and its Effects on the Native American Population and the Environment in North America (see http://adr.coalliance.org/codr/fez/eserv/codr:745/RUGFM018.pdf ). For more information on the commodities of Native American trade, see “Indigenous Trade: The Northeast.” American Eras. 1997. Encyclopedia.com. 19 Mar. 2015, at http://www.encyclopedia.com.

20. See David Allen’s 2005 French Mapping of New York and New England 1604-1760 at http://purl.oclc.org/coordinates/a1.htm . And Bernard Hoffman’s 1955 Map of Native Territories in 1700, in Souriquois, Etechemin, and Kwedech–A Lost Chapter in American Ethnography, in Ethnohistory 2 (1). For a perspective on ethnicity in the Northeast, see Bruce Bourke’s 1989 Ethnicity on the Maritime Peninsula 1600-1759, in Ethnohistory 36 (3) and Olive Dickason’s 2009 general reference, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (Oxford University Press).

21. A more complete account of this interaction and its potential for cross-cultural misunderstanding is given in Marc Lescarbot’s 1607 account, Defeat of the Armouchiquois Savages by Chief Membertou and his savage allies (translated by Thomas Goetz), in Papers of the sixth Algonquian conference, William Cowan, ed. (Carleton University, 1974).

22. For a perspective on conflict between Northeastern hunter-gatherers and New England horticulturalists, see Bruce Bourke and Ruth Whitehead’s 1985 article, Tarrentines and the Introduction of European Trade Goods in the Gulf of Maine, in Ethnohistory 32 (4).

23. The quotation is in Part XIII of Vol. II of Otis’s translations of Voyages and also on pages 6 and 7 of Morris Bishop’s Samuel de Champlain: The Life of Fortitude (Knopf, 1948).

24. Primary source accounts of Tarrantine raids on New England are in the papers of John Winthrop and John Winthrop Jr. Tarrantine raids on Cape Ann are also referenced in John Goff’s 2008 article, Remembering the Tarratines (sic) and Nanepashemet: Exploring 1605-1635 Tarratine War Sites in Eastern Massachusetts, in The New England Antiquities Research Association Journal, 39 (2). See also William Haviland’s 2010 Canoe Indians of Down East Maine (The History Press).

25. Scalping and scalp collecting were practiced in North and South America in pre-Columbian times in highly ritualized cultural contexts as an expression of a warrior code of conduct, including the scalplock hairstyle and collection of coups, during raids on other native people. The practice was transformed following European contact into acts of retribution performed by both Indians and colonists on combatants and non-combatants alike, often for bounty money. Popular present-day interpretation has it that colonists taught scalping to the Indians, but this simply is not true. Sound sources on this subject include James Axtell’s 1982 The European and the Indian: Essays on the Ethnohistory of Colonial North America (Oxford University Press); John Grenier’s 2005 The first way of war: American war making on the frontier, 1607-1814 (Cambridge University Press); and Richard Burton’s 1864 ethnographic “Notes on Scalping” in Anthropological Review (http://archive.org/stream/jstor-3025136/3025136#page/n1/mode/2up ).

26. See Note 23.

27. For a perspective on unintended impacts of French contact on relations among the Indians, see Champlain’s Legacy: The Transformation of Seventeenth-Century North America, in The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America, 1500-2000, by Fred Anderson and Andrew Clayton (2005) and Colin Calloway’s 2013 New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America (Johns Hopkins Press).

28. Champlain’s map of Gloucester Harbor is surprisingly accurate, based only on his astrolabe readings and pacing off of the land. Captain John Smith’s mapping of Cape Ann is described in more detail in the next chapter. The original of Champlain’s 1607 map of the Northeast from Cape Sable to Cape Cod is in the Library of Congress.

29. French and other historical units of measure are explained in Measure for Measure by R. A. Young and T. J. Glover (Blue Willow, 1996). The vessel that Champlain moored in Gloucester Harbor may have been the Don de Dieu, described in William Wood’s 1915 All Afloat: A Chronicle of Craft and Waterways, or possibly a smaller barque built on the St. Lawrence specifically for exploring the northeastern coast, with an even smaller oared vessel in tow—a shallop or pinnace—for exploring up rivers en route. The contemporary map of Gloucester Harbor is a detail from the NOAA Nautical Chart for Ipswich Bay to Gloucester Harbor. The history of Gloucester Harbor, a fascinating study in itself, is found in publications of the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, including a 2000 report, Review of Depth to Bedrock in Gloucester Inner Harbor and The Environmental History and Current Characteristics of Gloucester Harbor by Anthony Wilbur and Fara Courtney (2001): http://www.mass.gov/czm/glouc_harb_rpt_ch1.pdf .

30. Champlain’s maps have been gathered in the Osher Map Library, including engravings of his maps of the St. Lawrence and the Saco River. : http://www.oshermaps.org/exhibitions/creation-of-new-england/ii-samuel-de-champlain-and-new-france .

31. Champlain’s 1605 map of Plymouth Harbor, which he named Port St. Louis, may be seen on the web site of the Plymouth Colony Archive Project at http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/maps.html. See also a description of his visit there at http://www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/pdf/Champlain_Map_and_Description.pdf.

32. Champlain’s experience at Nauset and his map of Malle Barre are from Part XIV of Volume II of Otis’s translation of Champlain’s Voyages.

33. Champlain named Stage Harbor in Chatham Port Fortune and later Port Misfortune. See https://bostonraremaps.com/inventory/samuel-champlain-chart-chatham-port-fortune/. There are different stories about Champlain’s misadventure there, including an “official” local history that attributes loss of life to the theft of a knife. I have relied on Champlain’s account of what happened there, in which there is an unprovoked Wampanoag attack on men put ashore to bake bread and see to the provisioning of their vessel, although the previous French attack on Nauset people may well have been provocation enough. The map story of this attack is Marc Lescarbot’s elaboration of Champlain’s original chart of the harbor.

34. For information on the founding of New France, I relied on Canadian sources, especially W. R. Wilson (2010) Eastern Woodland Indians & the Coming of the Europeans and New France, in Early Canada Historical Narratives at http://www.uppercanadahistory.ca/fn/fntoc.html ; D. Garneau’s History of New France, in Canadian History Timelines (http://www.telusplanet.net/dgarneau/direct.htm ); and the Canadian History Directory (2009), Timelines for the History of New France 1385-1900: (http://www.telusplanet.net/dgarneau/direct.htm ). See also Francis Parkman’s 1983. Pioneers of France in the New World: the Jesuits in North American in the Seventeenth Century, in Volume I of France and England in North America (Library of America). Game was more plentiful northern New England than in southern New England, a factor that Champlain considered in siting the capital of New France on the St. Lawrence River. Game in New England principally included (in addition to elk, moose, and bear) white-tailed deer, beaver, otter, fox, fisher (marten), muskrat, raccoon, Eastern cottontail rabbit, snowshoe hare, porcupine, opossum, and squirrel, all of which are still found in New England. Francis Higginson also reported “Lyons” on Cape Ann and “great wild cats”, which may have been mountain lions, cougars, and/or lynxes. In the seventeenth century English colonies offered bounties on lions and wolves.

35. Champlain’s sketch of himself firing his arquebus at an Iroquois war party in 1609 is reproduced in the Otis edition of Voyages and elsewhere. No authentic portrait of Champlain is known to exist. The painting most commonly used shows Champlain as a d’Artagnan-like figure by Theophile Hamel (1870) after one by Ducornet (d. 1856), based on an earlier portrait of someone else entirely by Balthasar Moncornet (d. 1668).