The Native Americans who lived on Cape Ann most recently, known as the Pawtucket, were also called the Agawam and the Wamesit by colonists and early historians. All three names refer to places—villages—rather than to people or territories, however, and they were all the same people. Confusion over group names arose partly because the Algonquians of New England usually referred to themselves simply as belonging to a village, or as “the people”(Ninnu) or “the real/original people” of whatever place or landscape they were in at a given time (Ninnuock, “the people here”). Place names usually were not unique, furthermore, but could apply to any location where the landscape had the same geographic or ecological features. There are other places called Agawam and Pawtucket, for example. People understood from local context the particular place of the same name that was being referred to. Another source of confusion in Algonquian place names is European observers’ mistakes in hearing, transcribing, and translating the words.1

In Essex County, most translations of Pawtucket place names we have today are not correct. One reason is that linguists have theorized on the basis of the wrong languages—John Winthrop’s notes on Pokanoket, for example, or Roger Williams’s dictionary of Narraganset, John Eliot’s translation of the Bible into Massachuset, John Trumbull’s dictionary for Natick, and later linguists’ work, for example on Delaware and Wampanoag. However, the Pawtucket of Essex County originally came from New Hampshire and southern Maine and spoke a different language, a dialect of Western Abenaki. Abenaki-derived languages thought to have become extinct include Nipmuc and Pennacook, known as Loup languages (Loup A and Loup B) in French ethnographic terms. It is unlikely that the Pawtucket knew the languages of southern New England except as needed for trade and alliance. Early explorers observed as much.2

Another reason that we have incorrect translations is that in writing Algonquian words Europeans not only did not understand the intricate grammar but also had difficulty speaking and transcribing phonetically the unfamiliar sound combinations they were hearing. Algonquian word order is object-subject-verb, Yoda-like, and pluralization is accomplished by a k sound in the middle of a word for singular, and g sound for plural (e.g., wikwam, wigwam). Algonquian languages are highly nasalized and include glottal stops, for example, which French, Dutch, and English speakers transcribed variously and inconsistently as /qu/, /k/, /g/, or /’/, making it difficult to know from transcriptions exactly how Algonquian speakers pronounced words. (A chapter appendix offers a pronunciation guide for saying Algonquian names.) In using present-day reconstructions of Abenaki dialects to analyze Pawtucket words and introduce new translations, my work departs from a large body of earlier linguistic research.3

Place Making

Colonial observers who met “the people” at Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack River between Lowell and Lawrence, where they gathered in spring in large numbers to harvest river herring, or alewives, called them the Pawtucket. This history chooses that term to refer to the Native Americans who occupied Cape Ann and the rest of Essex County during the last thousand years or so. Pawtucket or Pautukit means “At the falls on the tidal river”, in this case referring to the Merrimack (Abenaki Molodemak). The people fished there in April en route from the winter village of Wamesit to their summer camps and villages on the shores of Essex County. Pawtucket is a place name in other areas as well, notably Pawtucket, Rhode Island, which topographically is also on the Atlantic fall line. (Pawtuxet, with the diminutive /s/ sound in the middle, referring to another site in Massachusetts, means “At the falls on the small tidal river”).4

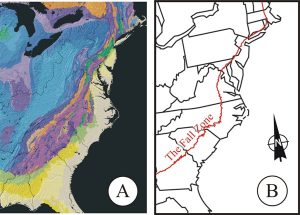

The fall line marks the drop in elevation between the Appalachian piedmont and the coastal plain all along the Atlantic seaboard. To Native Americans the fall line represented the place on tidal rivers and streams where fresh water and salt water meet, an optimal site for fishing and the location of many villages. In New England topography and Pawtucket place names, the histories of Native Americans and Europeans intertwine, and these intertwined stories move forward and backward together in time. River sites had economic importance for both groups. River junctions where natives camped or erected villages became the sites of the first colonial trading posts, for example, and falls where the people fished became the sites of the first watermills.5

Cities of the East are located along the Atlantic Fall Line, which extends from Alabama to the Canadian Maritimes. Native American villages and the earliest European settlements also were sited on falls, which often required portages to travel further inland by water. On the North Shore of Massachusetts the fall line is near the ocean, with the coastal plain broadening to the south.

Colonists who encountered “the people” in their permanent winter village of Wamesit (Wah me sit) in what is now Lowell at the junction of the Merrimack and Concord rivers, (which was part of Chelmsford, Billerica, and Dracut in colonial times), called them the Wamesit after the name of their village of around 2,500 acres. Wamesit (also Wamoset) was said to mean “Here is space for all”, referring to all the people who otherwise lived on the coastal saltmarshes. Wam (or wamph) was the root for “submerged land” or “land overflowed with water”. Agawam, referring both to a Pawtucket village on Castle Neck River in Ipswich and the larger territory of which it was a part, means “Other side of the marsh,” and Wenesquawam—Wonasquam on old maps and the name from which Annisquam is derived—means “End of the marsh.”6

Today, the site of the Pawtucket village of Wamesit is partly buried under a Home Depot but otherwise remains largely undeveloped, framed by rock piles and overgrown with new forest.

The marsh referred to is the Great Salt Marsh that stretches down the Gulf of Maine from Hampton, NH to Cape Ann. In present-day reconstructed Abenaki, the “End of the marsh” name for Cape Ann would be written as Wanaskwiwam. Because of the nature of Algonquian place name construction, places are purely descriptive of the environment or its resources and thus are not uniquely named. There are other places named Agawam, for example, and Wamesit is also a present-day place name for a neighborhood in nearby Tewksbury, a street in Billerica, and a town near Portsmouth, New Hampshire.7

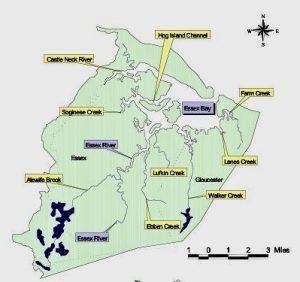

The village of Kwaskwaikikwen (“Quascacunquen”) in Newbury was in the north of The Great Marsh, the area outlined in red. The village of Agawam was in Ipswich on the “other side of the marsh”, and the village of Wanaskwiwam was in Gloucester at the “end of the marsh”.

The village of Kwaskwaikikwen (“Quascacunquen”) in Newbury was in the north of The Great Marsh, the area outlined in red. The village of Agawam was in Ipswich on the “other side of the marsh”, and the village of Wanaskwiwam was in Gloucester at the “end of the marsh”.

The English settlers who encountered the Pawtucket in Ipswich, Essex, and Cape Ann in the summers called them the Agawam Indians, a term still used today. Agawam is also a place name on colonial maps for an area that encompasses Gloucester and Rockport and the rest of eastern Essex County, including Manchester, Beverly, Essex, Ipswich, Hamilton, Wenham, Rowley, Georgetown, Topsfield, Boxford, Newbury, and Newburyport. The last recorded Contact-era sagamore of Agawam, whom the colonists called Masconomet or Masconomo and later Sagamore John, and his descendants signed over the deeds to these towns. This history thus is incomplete without the local histories of these other towns and beyond, for they were all part of the Pawtucket story.8

Geographic Descriptors in Algonquian Place Names

Following are some examples of how syllabic descriptive phonemes are used in the construction of Algonquian place names, keeping in mind that there are, as always, questions of accuracy as well as alternative spellings and interpretations. My sources for this chart are William Bright (2004), Native American Placenames of the United States; R. Douglas Lithgow (2000), Native American Place Names of Massachusetts; Huden (1962), Indian Place Names of New England; Frank Waabu O’Brien (2010), Understanding Indian Place Names in Southern New England; and Myron Sleeper (1949), Indian Place Names in New England.

| Algonquian | Variations | Meaning | Examples | |

| adin | ahdin, aden | Mountain, hill, highland, height | Katahdin, Winniahdin. Monadnoc | |

| adum | ogum, ogun, ammun, bun | dune, bank, sand bar, gravel bar | Kennebunk, Ogunquit | |

| kenne- | kenni-, quine, quinni | long | Kennebec, Kennebunk | |

| quit | quet, ket | pool, lagoon | Ogunquit | |

| bec | bic, pec | quiet water | Kennebec | |

| ponqui | ponka | shallow | Ponkapau | |

| paug | pog, baug, boag | pond | Ponkapaug | |

| sau(k) | saco, saug | river outlet, estuary | Saugus, Winnipesauke, | |

| -s | -s-, -us, -es,

-ux- |

small, little | Saugus | |

| win | winni | vicinity (of), around, near | Winnipesauke,Winnebago, Winniahdin | |

| nebes | Bes, bis, bego, bago | lake | Winnebago | |

| -pe | -pe-, -pee, -ippi, -p | waters | Winnipesauke, Mashpee, Sunapee, Chicopee, Mississippi | |

| mash | ash, ashue | between | Mashpee | |

| sun | suna, assin, asson, assa | rocky | Sunapee | |

| chico | chica, chika | rapid | Chicopee | |

| mack | mac, maq, mic, mec, muck | river | Merrimack | |

| merri | mer, mur | deep; also sturgeon | Merrimack | |

| tuck | tuc, tik, tic, tick, tek(w) | tidal river or stream | Pawtucket, Pentucket, Mistick | |

| pa | paw, pau | falls | Pawtucket | |

| pen | pinna | winding, bending | Pentucket | |

| et | it, ut, ot, ott, -t | at, near, about

|

Pawtucket, Pentucket, Massachuset, Swampscott | |

| mass | massa, mash, messa | big, large | Massachuset | |

| hass | hassun, ashim, shim, asnun | stone, stoney | Cohasset | |

| co | coo, ko-, -co, -acco | continuous area, ongoing, abundant | Cohasset, Pennacook, Chebacco | |

| chebe- | cheba-, chebac, chappa- | separate, in between | Chebacco | |

| keag | keak, kik, ki, ke, -ik, -k, -ic, -oc, og | land, area, place | Amoskeag, Naumkeag, Pennacook | |

| namas | nemas, anam, anas, anis, nam, naum, na-, ne-, amo(s), amaug | fish, fishing | Naumkeag, Amoskeag | |

| mis | mish, mi, misi, missi, meshe | great (repeated = very great) | Mishawam, Mistick, Mississippi | |

| adchu | achu, watchu, chus | mountain | Massachuset, Wachuset | |

| shawm | shaum, shawam, shawom | neck of land, peninsula; also canoe landing | Shawmut, Mishawam | |

| squi | squa, swa, sw- | red | Swampscott | |

| ompsk | ompsc, ampsc | rock | Swampscott | |

Agawam

Agawam was not the name of an Indian tribe but an anglicization of an Algonquian place name for a presumed sovereign territory and its village seat. The concept of sovereignty—like those of clan, tribe, nation, chief, king, and queen—is a European construct based on European history. European contact agents imposed these constructs to such an extent that they altered reality as Native New Englanders began to adopt them for themselves.

Early explorers, such as John Smith, whose 1616 and 1628 maps show Tragabigzanda and Cape Anna respectively, and colonial mapmakers, such as William Wood (1635), wrote Aggowom, Agawammin, Agawanus, or Igowam on their maps or in their accounts.9

According to Wood (See note 17 on the detail map):

Agowamme is nine miles to the North from Salem, which is one of the most spacious places for a plantation, being neare the sea; it aboundeth with fish, and flesh of fowles and beasts, great Meads and Marshes and plaine plowing grounds, many good rivers and harbours and no rattle snakes. In a word, it is the best place but one, in my judgement, which is Merrimacke, lying eight miles beyond it, where is a river twenty leagues navigable, all along the river side is fresh Marshes, in some places three miles broad. In this river is Sturgeon, Sammon, and Basse, and divers other kinds of fish….10

Today Agawam appears in other place names, such as the town of Agawam, Massachusetts, on the Connecticut River; a district in Wareham; and a Connecticut town. In its entirety, Pawtucket territory extended from the Merrimack River Valley on the north to Salem and Marblehead on the south and to the Concord and Danvers Rivers on the west. English colonists later reserved “Squam” for Cape Ann and “Agawam” (later Ipswich) for the larger territory. To the Pawtucket the name for the larger territory probably referred to the Great Marsh, the salt marsh that starts south of Portsmouth New Hampshire, runs down the Gulf of Maine, and ends at Cape Ann.

Colonists tended to ascribe the meanings of Algonquian place names to the activities they observed there, deriving “fish securing place” or “fish curing place” for Agawam, for example. Algonquian place names all describe landforms or resource sites, however, not activities. Furthermore, the Algonquian root words for “fish/fishing” (nam/nahm/nahum) do not appear in Agawam. The word is also defined as “low land beneath water” (or marshland, [wam(ph]), as “ground overflowed by shallow water”, and as “a place where one must unload canoes for portage”. These definitions apply to all places so named and probably are more accurate as translations or interpretations than “fish curing place”.

I decided that Agawam must mean “Other side of the marsh,” referring to the location of Agawam Village on Castle Neck River in Ipswich.11 According to my language coach Sasachiminesh, however, in Algonquian the irreducible root for “other side/beyond” is kom, appearing with extension particles in constructions such as akomink. This means that Agawam itself is a corrupted word and the placename and its meaning remain uncertain. Based on reconstructed Abenaki, the original name perhaps was Akomiwam or Agominam and most likely meant “Other side of the marsh” or “other side of the fishing”, in the latter case referring to the string of landforms on the seaward side of Plum Island Sound.

The interchangeability of descriptive elements for geographic locations, such as akomin- (“beyond/other side”), can be seen in the place name Agamenticus. According to the Boston Archives, settlers referred to Gloucester as Agamenticus, and West Gloucester as Agamenticus Heights, after native appellations. What did this mean? There was also an Agamenticus in Maine, plus a mountain and a river by that name, and the Massachuset referred to the Charlestown area as Agamenticus as well!12

This is a good example of how Algonquian place names worked. The syllables that made up the name of a place described that place. Elements of a place name also could vary grammatically depending on the speakers and intent and whether the subject was regarded as animate or inanimate, which helps account for the many variations in spelling of Algonquian names that Europeans attempted to record phonetically.

Agamenticus

Translations into English are equally diverse. For example, Maine’s Mt. Agamenticus has been translated to mean “Beyond-the-hill-little-cove” (in this case, the cove where the Little York River meets the sea). The term could have described the opposite, however: “Beyond the hill rising from the small tidal river when viewed from the cove”. The assumption that viewpoints were toward the sea from the land is a European perspective. Algonquian place names tended to describe landforms as viewed from bodies of water.

Deconstructing Agamenticus

| Algonquian | Agamen | tic | us | |

| Dialectical & spelling variations | Akomin, Accomen | tik (tick), tuc (tuck)

|

es, -s | |

| English translation | Beyond, other side, below, beneath | (the) tidal river (that is) | small |

Thus, Agamenticus in Maine may mean “Beyond the Little York River viewed from where it empties into the Gulf of Maine”. The description distinguishes this location from beyond the larger York River just to the south. Agamenticus in Charlestown may mean “Beyond the Little Mystic River viewed from where it joins the Mystic and flows into Boston Harbor”, distinguishing that locations seen from the mouth of the larger Charles River just to the south. As Agamenticus, West Gloucester may have been “Beyond the Essex River (which is a smaller tidal river than the Annisquam just down the coast) as viewed from Essex Bay. There are many other places in New England with this place name. Agamenticus could be used to describe any location beyond any comparatively small tidal river, the specific identity of which would be clear to the speakers in local geographic context.

Questions about the derivation of the state name of Massachusetts illustrate the challenges of reconstructing Algonquian place names. For Massachusetts there are three candidates: 13

- Messatscosec (mess/mass = “great” [size]+ atsco = “continuous high land or chain of hills” + sec/sac/saco (also sauk) = “mouth” = “Entrance to the great hills”), possibly referring to what is now the Blue Hills State Park.

- Massawachuset (massa = “great” [feature] + (w)achu/(w)adchu = “mountain” + s = “small” + et = “at/on/in” = “At the great(est) small mountain”), probably referring to Great Blue Hill (635 feet and the highest of the 22 hills).

- Moswatuset (mos = “great” [person] + watus = “chief’s hill” + et = “at/on/in” = “At the great chief’s hill”), referring to the sachem there at the time of contact. Moswatuset was also a term for “arrowhead”. Moswatuset Hummock in Quincy is an actual place in the Blue Hills—an arrowhead-shaped mound in the National Register of Historic Places that was the sachem Chickatawbut’s seat of power. It was Chickatawbut (or Chickataubut, Chikkatabet) whom Myles Standish and Squanto met in 1621 on what is now Quincy Shore Drive.

The earliest colonial accounts use diverse spellings for Massachusetts; for example, one refers to Mattachusit Bay Colony and another to the Masswatuset Bay Colony! The name of our state thus is perhaps a mash-up of the Algonquian placenames Massawachuset and Moswatuset.

Quascacunquen

Most Agawam place names are no longer in use or have been corrupted almost beyond recognition. An example is Wessacuçon, said to be named for a waterfall on the Parker River. It was used as the name of the English plantation that became Old Newbury. Wessacuçon was also transcribed as Quascacunquen and was recorded as the Pawtucket name for the Parker River, its falls, and the Pawtucket village upon it. The word is retained today as the name of a Masonic lodge. The meaning of Quascacunquen did not have anything to do with a waterfall or the Parker River, however. Based on present-day reconstruction from Western Abenaki, the name would be written Kwaskwaikikwen and would mean “just right for fields [for planting corn]” or “best fields to plant” or “perfect cropland for growing [corn]”. Interestingly, Quascacunquen encapsulates the Abenaki word for corn [ska]. In all of Agawam the upland intervales of the Parker River tributaries provided the best soils and conditions for farming. The location of the village was most likely near Old Town Hill in Newbury where the Little River meets the Parker River. An indigenous presence in West Newbury near headwaters of the Artichoke River, tributary to the Merrimack, was preserved in the name Indian Hill.14

Kwaskwaikikwen

Kwask = state of being

wai = “best”, “ideal”, “perfect”

kikwen = “fields”, “planting ground”, “cropland”

Wonasquam

Another example of difficulty with language is attempts to explain the meaning of Wonasquam, seen on the earliest colonial maps and assumed to be a corruption of the original Pawtucket place name for Annisquam. According to Josselyn in his account of his second voyage to New England in 1663 (transcribed here by me from Restoration English):15

“To the Northward of Cape Ann is Wonasquam, a dangerous place to sail by in stormie weather, by reason of the rocks and foaming breakers. The next Town that presents itself to view is Ipswich….Six miles from Ipswich Northeast is Rowley, most of the inhabitants have been Clothiers….Nine miles from Salem to the North is Agowamine, the best and spaciousest place for a plantation…. Beyond Agowamin is situated Hampton near the Sea coast….Eight miles beyond Agowamin runneth the delightful River Merrimack or Monumach, it is navigable for twenty miles….”

The existence of an Indian village named Wonasquam in Gloucester is attested in a letter written in 1696 by John Dunton, a London bookseller visiting Ipswich to see friends to to determine if New England could constitute a new market for his wares. He describes an overland trip to Gloucester with an Indian guide and a woe-begone village in which the Indians were in black faceprint mourning an unidentified great loss. Dunton also noted that most people in Gloucester were illiterate and had no need of books. 16

The linguist William Bright, following J. Hammond Trumbull’s 1860s studies of Native American languages, determined the meaning of Wonnasquam to be “at the top or point of the rock” (wanashque = “at the top of” or “at the extremity of”, or wunnashque or the variant annaqua = “at the end of”, + omsk = “rock”). Geography supports this interpretation, as anyone will attest who has visited Cape Ann’s giant glacial erratics or has stood on the massive pluton outcrops (intrusions of igneous rock through the bedrock) overlooking Ipswich Bay. 17

Trumbull’s analysis of “rock” in his 1870 work, The Composition of Indian Geographical Names included source information from John Eliot’s Algonquian Bible, Roger Williams’s and John Winthrop’s journals, and the dictionaries of French missionaries:

ROCK. In composition, -PISK or -PSK (Abn. _pesk[oo]_; Cree,_-pisk_; Chip. _-bik_;) denotes _hard_ or _flint-like_ rock; -OMPSK or O[N]BSK, and, by phonetic corruption, -MSK, (from _ompaé_,’upright,’ and _-pisk_,) a ‘standing rock.’ As a substantival component of local names, _-ompsk_ and, with the locative affix,_-ompskut_, are found in such names as…Wanashqui-ompskut_ (_wanashquompsqut_, Ezekiel xxvi. 14), ‘at the top of the rock,’ or at ‘the point of rock.’ _Wonnesquam_, _Annis Squam_, and _Squam_, near Cape Ann, are perhaps corrupt forms of the name of some ‘rock summit’ or ‘point of rock’ thereabouts._Winnesquamsaukit_(for_wanashqui-ompsk-ohk-it_?) near Exeter Falls, N.H., has been transformed to _Swampscoate_ and _Squamscot_. The name of Swamscot or Swampscot, formerly part of Lynn, Mass., has a different meaning. It is from _m’squi-ompsk_, ‘Red Rock’ (the modern name), near the north end of Long Beach, which was perhaps “The clifte” mentioned as one of the bounds of Mr. Humfrey’s Swampscot farm, laid out in 1638._M’squompskut_ means ‘at the red rock.’ The sound of the initial _m_was easily lost to English ears.18

Other interpretations of Wonasquam are possible, however. For example, the Algonquian root word for Atlantic Salmon was m’squammaug, often shortened to m’isquam, or ‘isquam, because English speakers tended to omit the initial -m’- and did not produce glottal stops. An alternative origin for Annisquam thus could be Nam’isquam (salmon fishing), with the addition of won-, a prefix for “good” or “abundant”. Thus, Wonasquam, could have meant, literally, “good salmon fishing”. The Annisquam River empties into Ipswich Bay beside Wingaersheek Beach, and until around 500 years ago (and before the Cut), it is not impossible that Atlantic Salmon entered the river to spawn, along with alewives and shad.

Trumbull cautions, however, that interpretations of Algonquian place names must observe certain rules. First, every letter or sound had its own value; the omission or addition of a letter for “euphony” (the quality of being pleasant or smooth sounding) is a sign of misinterpretation. So, where in Wonasquam is the /psk/ or /bsk/ sound required for “rock”? Second, even when abbreviated, words retain their significant roots rather than appearing as fractions of words. So, if /ompsk/ is the root word for “rock”, wouldn’t it have been retained in the name at least as Wonasquompsk (“good rock-top” or “good summit”)?

Squam Lake in New Hampshire in the heart of Pennacook territory is derived from asquam, a Western Algonquian root for “water”, referring to fresh water lakes. Using that root, Wonasquamsauke would translate simply as “good water outlet” or “good water entrance”, but it would have the wrong geographic context as it refers to lakes rather than to the sea. Henry Schoolcraft translated that name incorrectly as Wonne (“beautiful”) asquam (“water”) (s)auke (“place”), with the /s/ thrown in to make a pleasing sound. Sau actually meant “outlet or mouth of a river”, however, not “place”, which was denoted instead by the locative suffix ohke, ahke, ake, ke, ki, or k. Neither does squam mean “harbor” (in any language), as Cape Ann web sites and tourist brochures claim. So, having Wonasquam (and thus Annisquam) derive from “Beautiful Water Outlet” or “Pleasant Harbor” works no better than “Top of the Rock”.19

Winnesquam is said to be Abenaki for “good salmon fishing”, and there is a lake by that name in New Hampshire today near Laconia in the Pawtucket-Pennacook homeland. However, this name probably is not based on the word for salmon but on combined elements for “fishing” and “fresh water”: nesquam. In Abenaki, win/winni- is not a variant of won/wonne and thus does not mean “good” or “beautiful”. Rather, win/winni- is a prefix for “hereabouts” or “in the vicinity of”. Thus, Winnesquam more likely means “there is fresh water (lake) fishing around here”.

You can see the problems we have knowing for certain what words in unwritten extinct or near-extinct languages mean. All the above alternatives are moot, however, because the original term on which all our Squam place names are based was not Wonasquam. It was Wenesquawam.

Wenesquawam

Annisquam most likely came not from Wonasquam but from Wanaskwiwam, first transcribed as Wenesquawam. This name appears in an ancient document in the archives of the British Library, written by an unknown English explorer sometime between 1600 and 1610. The document is known as “Ye Names of ye Rivers and ye Sagamores yte Inhabit Upon Them”, and it describes the larger tidal rivers from the Kennebec to the Annisquam, along with the names of their principal village or sagamore at the time. Often, a village on the river and the river itself bore the same name, and that was the case with Wenesquawam. Today the native village no longer exists (its location at that time most likely was in Riverview, Gloucester, north of Pole Hill, as attested in the historical memoirs of Ebenezer Pool of Rockport), but the modern Annisquam remains as the name of both the river and the peninsula guarding its entrance. 20

Wenesquawam

Western Abenaki Wenesqu = Wenesk(w) =

Wanask(w) = the end, as in

wanaskwigwen = “end feather of a wing”

wanaskwizida = “end of the foot; toes” +

wam = “land overflowed with water; marsh” =

Wanaskwiwam = “end of the marsh” =

Wenesquawam = Wonasquam = Annisquam = Squam

The name “End of the Marsh” accurately identifies the geographic location of the village by that name on the Riverview peninsula, which is at the end of “The Great Marsh” that begins in coastal southern Maine and ends at Cape Ann.

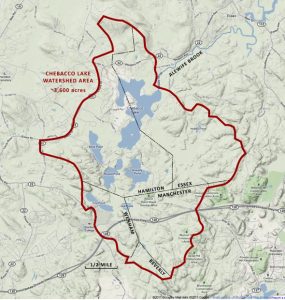

Chebacco

Today some regional place names such as Agawam (Ipswich) and Chebacco (Essex, which the Pawtucket may have pronounced Jebacho) survive as the names of companies, teams, parks, lakes, or neighborhoods. The most common translation is derived from Trumbull’s work, which was based on the Massachuset language, especially Natick.

Chebacco

Cheb/chebbe = “separate (in between)”

acco = “continuous area”

This interpretation makes the most likely meaning of the Chebacco place name as “Continuous separate area [including the lake by that name and the headwaters of the Essex River] in between [the Ipswich and Annisquam river drainages]”. However, based on Western Abenaki as a more appropriate fit with the people who lived in Essex county, we find another translation, and one that is even more apt for the topography.

kchi/kitchi (pronounded by the English as chi/che) = “great”

bac/bec/ = (flat or shallow water) = “wetland/marsh”

co = “continuous area”

In this interpretation Chebacco means “The Great Marsh”, the name of this area today.

(Sources for this interpretation include Henry David Thoreau’s The Maine Woods: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42500/42500-h/42500-h.htm; Fannie Hardy Eckstrom’s 1841 Indian Place-Names of the Penobscot Valley: https://www.si.edu/object/siris_sil_152988; and Sebastien Rale’s (aka Rales, Rasles, Ralle), Abenaki dictionary, begun in 1691. (The manuscript of Rale’s dictionary is preserved at Harvard University. It was edited in 1833 by John Pickering in the Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (I, 375–574) under the title, “A dictionary of the Abnaki language in North America by Father Sebastian Rasles.”)

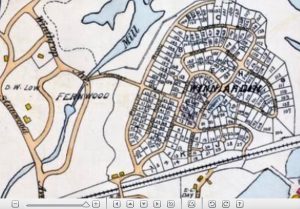

Winniahdin

Many other names are lost to time or are repeated despite remaining mysterious. Winniahdin, for example, is the name of an 1890 residential development, originally for summer cottages, on Stanwood Point on Little River between “The Cut” on the Annisquam and the Boston & Maine (MBTA) train line on Little River in West Gloucester. The development’s street names commemorate Native American leaders—Massasoit and Samoset from Mayflower times, Uncas and Canonicus from the Pequot War, and King Philip from his Wampanoag War. An early map ambiguously gives the name Winniahdin to the entire west bank of the Annisquam from the Cut to Little River. 21

Winniahdin

Winni = In the vicinity of

ahdin = the mountain

In Abenaki, as noted earlier, win/winni means “hereabouts” or “in the vicinity of”, and the root ahdin/aden/adn denotes “mountain” or “heights”, rendering “In the vicinity of the mountain” or “There is a mountain hereabouts”. Considering the immediate terrain on the banks of the Annisquam at Little River, the meaning of this rather prosaic name may be hard to imagine. Consider, however, the steeper elevations of “The Heights” and the Banjo Ponds—just across the road from the railroad tracks and Rte. 133—and Mt. Ann (or Thomson’s Mountain), the source of Little River, just to the west. As the highest point of Cape Ann, Mt. Ann would have had special significance to the Pawtucket, making Winniahdin an apt name for this location.

Naumkeag

Naumkeag has been translated as “still water dividing the bay” (Nahumbeak) or simply “the fishing grounds” (Na[u]m = “fishing” + keag = “grounds, land, place”). Based on Western Abenaki roots, however, this place name more likely meant “Eel land” or “Here are eels (to fish for)” (Nah(u)m = eels + keak = locative suffix (“here”). Atlantic Eel, a much-prized catch, is a catadromous species that goes from fresh to salt water to spawn and favors smaller rivers and still waters. Eels were eaten as a delicacy, the spine was dried and powdered for culinary use, and the soft strong skins were made into hair ribbons, tumplines, and cradleboard ties. According to colonial accounts the eels grew to great size. Algonquian appreciation of eels was remarked upon by several early observers, including Champlain, Wood, and Josselyn. Though smaller today, they are still abundant in the rivers that empty into Beverly and Salem harbors. The Pawtucket probably called their major village between the Bass and North rivers Nahmkeak, or Nahumkeak.

The village of “Naumkeag” was on the east bank of the Bass River, which the Pawtucket called the Wahquack, near its outflow from Wenham Lake and the surrounding wetlands. Eels were the preferred food of the striped bass, an anadromous species that migrated up the Bass River every spring.

Wingaersheek

The Pawtucket did not call Cape Ann “Wingaersheek”, however, as early historian John Babson claimed in 1860, without citing his source. The source would have been John Winthrop via John Endecott, as reported by Endecott’s surveyors, sent to Cape Ann to describe the lay of the land in 1637. Their report is lost, but the story is that they encountered Indians, asked them the name of Cape Ann (a geographic construct that would not have figured in Pawtucket reckoning), and were told “Wingaersheek”. As written, however, Wingaersheek is not a native New England Algonquian word. It also does not mean “Beautiful breaking water beach”, as Robert Pringle, a local journalist and Cape Ann publicist, had it in 1890, based on Henry Schoolcraft’s faulty attempts at ethnolinguistics. Historian E. N. Horsford claimed that the name is a corruption of a 17th-century loan word from Dutch Low German: Wyngaerts Hoeck for “Wine (or grape) garden peninsula (or land)”. The Dutch left this name on a map, in the sea off the Massachusetts coast, but it had nothing to do with the Indians. The Dutch had little or nothing to do with Cape Ann, and if they had, more than one place name here would be attributable to them today.22

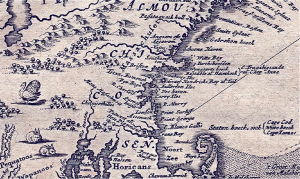

Horsford based his claim on this 1671 map of “New Belgium” by the Dutch explorer, Arnoldus Montanus, in an etching by John Ogilby published in 1673. Wingaerts Hoeck is below Witte (White) Bay, our Sandy Bay.

The full title of the work in which the map appears is The New and Unknown World: or Description of America and the Southland, Containing the Origin of the Americans and South-landers, remarkable voyages thither, Quality of the Shores, Islands, Cities, Fortresses, Towns, Temples, Mountains, Sources, Rivers, Houses, the nature of Beasts, Trees, Plants and foreign Crops, Religion and Manners, Miraculous Occurrences, Old and New Wars: Adorned with Illustrations drawn from the life in America, and described by Arnoldus Montanus. Montanus, in turn, based his map largely on Capt. John Smith’s 1624 map of New England.23

Wingaersheek is most likely an English corruption of an Algonquian word. In “extinct” Algonquian dialects of eastern Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine, the /r/ and/or the /l/ phone was not used in speech, as noted by early settlers. Explorers at Sagadahoc on the Kennebec River noted in 1622, for example, that nobsten was the closest pronunciation for lobster that the Native Americans there seemed capable of saying. In 1654, 1674, and 1721, Indians—undoubetly Abenaki speakers—were reported as referring to the Merrimack River as the Monumach (Monomack, Monnomacke, Monumack). Likewise, the Pawtucket name for the beach at the mouth of the Annisquam River probably would not have included the /r/ sound at the center of Wingaersheek.24

Elizabethan and Tudor English speakers, however, often added an /r/ sound to syllables ending in /a/. Listening to Yankee grandparents, for example, one may hear that Anner had a good idear. Thus the middle syllable in Wingaersheek may have been an Englishism or an error in transcription, and the word more likely is a corruption of a Pawtucket placename in their Abenaki-related Loup language, perhaps something like Wingawecheek.

Wingawecheek

Winga = “snails, periwinkles, whelks”

wechee = “ocean, sea”

–k = (locative) at, on, here =

“Here are sea whelks (of the kind used to make white wampum)”

When asked the name of Cape Ann the Pawtucket replied with the name of their settlement or camp where they were no doubt collecting shell to be made into wampum beads and other things as part of their resource procurement cycle. The wigwams would have been located mostly likely at the site of Old Coffin Farm between the dunes and the Jones River outflow. Another Pawtucket Contact-period archaeological site, the Matz site, was found behind Wingaersheek Beach off Atlantic Street, facing the Jones River Salt Marsh. Artifacts from the Matz site, including whelk shells, are in the Harvard Peabody Museum in Cambridge. “Sea snail place” or the like would have been an apt name geographically, and whelk shells were certainly an important cultural and economic resource. The coastal Algonquians used whelk shells to make white wampum beads, and quahog shells to make the purple ones, a subject taken up in more detail in another chapter. Wampum shells, beads, strings, and belts were central to many social and political practices, were traded from the coast as far inland as the Mississippi Valley, and at one time served as official currency in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.25

Single wampum beads were made from what we call periwinkles, while several bead blanks could be cut from the cores of channeled and knobbed whelks. The Matz site under Cape Ann Campground was excavated in the 1970s. In the 1940s amateur collectors discovered extensive evidence of long-term Native occupation of the site that became Old Coffin Farm.

Aerial View of Wingaersheek and AnnisquamIn this view the Jones River Salt Marsh, the site of Old Coffin’s Farm, and Wingaersheek Beach are on the Annisquam River, facing Lobster Cove, Planter’s Neck, and Ipswich Bay.

As with corruptions of other Algonquian place names, such as Wonasquam, Wingaersheek has other defensible interpretations. For example, it could have been derived from an enemy’s name for the beach where they staged raids on the Pawtucket. Cape Ann had a long history of coastal raiding from the north by the Tarrantines of the Canadian Maritimes, who spoke a Mi’Kmaq-related Eastern Algonquian language. Tarrantines were hunter-gatherers of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia—traditional enemies of the agricultural Pawtucket. For as long as 500 years prior to European contact they swept down the coast in their ocean-going canoes to steal corn, kidnap women, and generally wreak havoc. The long sandy beach on the west bank of the Annisquam River, which wraps all the way around to Two Penny Loaf at the western end of today’s Coffin’s Beach, was a good landing place and perhaps the only one with any hope of concealment. The enemy’s name for that beach may have stuck; that is, Wingaersheek could conceivably derive from the Mi’Kmaq— Winnaguntwecheek: win = “along/in the vicinity of” + nagunt = “sand” + wecheek = “at the ocean/sea” = “Along the beach (where we gain access to the enemy’s river)”.26

Pennacook

Alternative translations of Algonquian place names are common, depending on the source language used and interpretations of the landscapes on which place names are based. Pennacook, for example, begins with syllables /penna/ that have been construed as “low hill” or “foothill” or “bottom of a hill”, followed by a construction for continuousness /coo/ and a locative /k/. Several hills in the southern White Mountains have been offered as candidates, for example, Sugar Ball Hill, a favorite place of the New Hampshire grand sachem Passaconnaway. Present-day Pennacook translations prefer “At the foot of the steep-sided hill”. Another way to read that word, however, is with syllables for groundnuts (Apios), /pennak/, potato-like tubers, a survival food for Indians and colonists alike. The construction for “continuous”, /co, coo/, refers to surface area, as in Chebacco, but also means “ongoing”, “rolling,” “undulating,” “plentiful,” and “abundant,” depending on context. 27

In addition, many Native American names for tribes and places are exonyms—other peoples’ names for them. Mohawk, for example, is derived from the Narraganset phrase mohowaùuck’ which meant “man-eaters”. The Mohawk’s real name for themselves in their native Iroquoian language was Kanien’kehá:ka (“People of the first flint”), referring to the eastern-most geological presence of flint in New York state, which is rare in New England. In any case, it is clear that “Wingaersheek” originally was an Algonquian, not a Dutch, placename.28

But that’s the challenge with history, it seems: We have to give up what we think we know to consider new interpretations. And we have to look beyond our borders—go over the bridge, so to speak—and Cape Anners will know what I mean by this—to really understand who we are and what’s in a name. We have to go off island to find out how we are part of these ancient places called Agawam and Squam.

An Algonquian Pronunciation Guide

In Algonquian, the sounds f and v (fricatives) are not used, and the r and l sounds are rare. Stress is less pronounced than in English and is usually placed on the last or next to last syllable of a word, rarely on the first. All vowels are pronounced fully regardless of stress. In this book, most names are spelled phonetically, in simple orthography rather than in linguistic notation and without diacritical (accent) marks. Alternative spellings are given where found. The most complete information seems to be for Algonquian dialects spoken by the Wampanoag, Narraganset, Massachuset, Western Abenaki, and Eastern Abenaki. For more help with pronouncing Algonquian names and place names see Dr. Frank Waabu O’Brien’s appendix at http://www.bigorrin.org/waabu11.htm. In addition to the web site, O’Brien has published Understanding Indian Place Names in Southern New England (2010) and Guide to Historical Spellings and Sounds in New England Algonquian Languages, based on the research of colonial missionaries J. Eliot, J. Cotton, and R. Williams (2012). These works are part of The Massachusett-Narragansett Revival Program of the Aquidneck Indian Council (see the web site for details).

Vowels and Dipthongs

| As Written | Variants | As Spoken |

| a | ah, aa, á | Short a as in father (áe = ah-ee; áuke = ah-kee) |

| a | ei, ey | Long a as in lake (rare) |

| ai | ay, aj | Diphthong as in eye |

| au | aw | Diphthong as in caught, bought, raw |

| aw | ao, au, ow | Diphthong as in cow |

| e | ie, ee, ea | Long e as in he, green, ear |

| e | eh, ‘ (glottalized) | Short e as in bed, mess |

| i | ih, ii, ‘ (glottalized) | Short i as in hit |

| iw | eu | Diphthong as in reunion, feud |

| o | oh, ow | Long o as in bone, grow |

| oi | oy, oj | Diphthong as in boy |

| ô, â | an, aun, awn, on, anum | Nasalized, as in French Jean, bon, blanc |

| oo | ou | As in mood, food |

| u | à, uh, ah, aa | Short u (or schwa) as in sofa, cut |

| u | yu | Long u as in use |

Consonants

| As Written | Variants | As Spoken |

| b, p | bb, p, pp | big, pig, puppy, tubby (The bilabials are interchangeable) |

| c, k, q | cc, ck, kk, ckq(w), kw, kh | cow, account, kick, queen, sheik(h) |

| ce | ci, s | civil, cede |

| ch | chair, sachem (wadchu = wa-chew) | |

| d, t | dd, dt, tt | dip, tip, but, muddy, putty (The alveolar stops are interchangeable) |

| g | gg, gk, ‘(glottal) | go; gutteral as in German ach |

| gw | gwh, gh | Gwen, aarg(h) |

| h | hh | hot |

| j | dz, ds | Roads, juice |

| m | mm | mud, hammer |

| n | nn | sun, gunner |

| s, z | ss | sop, rocks, toes, mussel |

| sc, sk, sq | shk, shq, skc, skw | skill, musk, squid (gutteral) |

| sh | tsh | she, push |

| tch | ts | itch, tsunami, Betsy |

| w | ww | win |

| wh, wi | hw, hwh | what, why (a whistling sound) |

| y | yy, j, u (long) | yes, you, use |

The Algonquians were only the most recent people to live here to give their names to villages, rivers, and hills. Yet the archaeological record shows thousands of years of occupation before them. So who were the first peoples of Essex County?

Next: Why did we know so little about Indigenous history here?

Notes and References

- An explanation of Algonquian terms for identity appears in the first pages of Steven F. Johnson’s Ninnuock (the People): the Algonkian People of New England (University of Michigan Press, 1995). Sources for Algonquian place names include William Bright’s Native American Place Names of the United States (2004, see especially pp. 32, 41, 554, and 571); R. Douglas-Lithgow’s Native American Place Names of Massachusetts and his Native American Place Names of New Hampshire and Maine (2000); the chapter on Geographical Names in H. L. Mencken’s classic The American Language (1921, available at Bartleby.com); John Huden’s chapter on Indian Place Names of New England in Volume 18 of Contributions from the New York Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (1962, available at Archive.org/); and J. Hammond Trumbull’s vintage work, The Composition of Indian Geographical Names, Illustrated from the Algonkin (1870, available at Gutenberg.org). Other sources of information about place names are in Lyle Campbell’s 1997 American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (see pp. 156-168), and in articles by William Tooker (1904), Myron Sleeper (1949), and in C. Lawrence Bond’s 3rd edition book (2000) on the subject. Merrill McLane’s 1998 Place Names of Old Sandy Bay is a local, though inaccurate, source. The ethnographic basis for “the people” comes from Steven F. Johnson’s 1995 book, Ninnuock: the Algonkian People of New England (Marlborough, MA: Bliss Pub Co.).

- Some English explorers who recorded Algonquian words and names included James Rosier (in Henry Burrage’s 1887 Rosier’s Relation of Weymouth’s Voyage to the Coast of Maine, 1605); James Davies (Relation of a voyage to Sagadahoc, 1607-1608); John Smith (The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England & the Summer Isles, 1624); Christopher Leverett (A Voyage into New England Begun in 1623 and Ended in 1624); and Samuel Purchas (Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas his Pilgrimes, Volume 4, 1625). Some French sources, cited elsewhere, include Samuel de Champlain, Father Sebastien Rale, Father Jean de Brebeuf, and other Catholic missionaries posted to northern New England and Canada. For example, Jesuit missionary texts collected by Eugene Vetromille. published in 1857 as the Indian Good Book, include a Roman Catholic prayer book written in two Abenaki dialects.

- In addition to the sources cited above on anthropological linguistics, help reconstructing Pawtucket place names from the Abenaki came from Laura Redish, co-editor with Orrin Lewis of Native Languages of the Americas (2012) at http://www.native-languages.org; the Western Abenaki Dictionary and Radio Online at http://westernabenaki.com; and Cowasuck [Kowasek] Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People (the People of the White Pines) at http://www.cowasuck.org/language. A valuable historical source is Joseph Laurent’s 1884 New familiar Abenakis and English dialogues: the first ever published on the grammatical system, at http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.08895/5?r=0&s=1.

- English colonial observers in New England who recorded observations of Algonquian languages or names included William Bradford (History of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647); Edward Winslow (Mourt’s Relation, 1622, and Good Newes from New England, 1624); Roger Williams (A Key into the Language of America, 1643); John Winthrop (A journal of the transactions and occurrences in the settlement of Massachusett… from the year 1630 to 1644, published in 1853 as History of New England 1630-1649); John Winthrop Jr., who established Ipswich (The Winthrop Papers, 1628); Francis Higginson, who settled in Beverly-Salem (New England’s Plantation, 1630); William Wood (New England’s Prospect, 1634); Thomas Lechford (Plain Dealing: Or News from New England, 1637); Thomas Morton (The New English Canaan, 1637); Edward Johnson (Wonder-Working Providence, 1654), Samuel Maverick (A Briefe Description of New England and the Severall Townes Therein, 1660); John Josselyn (An Account of Two Voyages to New-England, 1674); John Eliot (A Brief Narrative of the Progress of the Gospel amongst the Indians in New England, in the Year 1670); and Daniel Gookin, the first Indian Agent for the government of Massachusetts Bay (Collections of the Indians in New England, 1792).

- In New England and to the northeast the fall line is very near the shoreline in contrast to the broad piedmonts in states to the south. This fact had significance for patterns of settlement and trade for both Native Americans and Europeans and also for differential effects on population in the spread of virgin soil epidemics. Sources consulted in this work for the geography and geology of Essex County include The Cape Ann Plutonic Suite by John Brady and John Cheney (2001); U.S. Geological Surveys, such as The Geology of Cape Ann, Massachusetts by Nathaniel Shaler (1888); The Physical Geography, Geology, Mineralogy and Paleontology of Essex County, Massachusetts by John Sears (1905); The Granites and Pegmatites of Cape Ann, Massachusetts by Charles Warren and Hugh McKinstry (1924); and Rocks of Cape Ann by W. H. Dennen (2001). The illustration of the Atlantic fall line is by Jeff Kaufman of Boston, http://enb105-2012s-drs.blogspot.com/2012/04/lab-8-fall-line.html.

- Some sources for Wamesit and Pawtucket include Eliot and Gookin, cited above; Charles Cowley’s 1862 Memories of the Indians and Pioneers of the Region of Lowell, Vol I. and his 1886 History of Lowell; Abiel Abbott’s History of Andover From Its Settlement to 1829; Wilson Waters’ History of Chelmsford (1917); Frederick Coburn’s History of Lowell and Its People (1920); and Silas Coburn’s History of Dracut, Massachusetts, called by the Indians Augumtoocooke….(1922). The photograph of Wamesit in the snow is courtesy of Peter Waksman from his Rock Piles weblog, http://rockpiles.blogspot.com/2008/01/wamesit-once-praying-indian-village-now.html.

- For more information on the Great Marsh and its significance, see the Mass. Audubon’s site summary at https://www.massaudubon.org/.

- Principal local histories of Cape Ann consulted for this chapter and throughout this book include John Wingate Thornton’s 1854 The Landing at Cape Ann; John Babson’s 1860 History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann: Including the Town of Rockport and the Notes and Additions to the History of Gloucester published in 1990; Herbert Adams’ 1882 The Fisher Plantation of Cape Anne, Part I of The Village Communities of Cape Ann and Salem, and James Pringle’s 1892 History of the Town and City of Gloucester, Cape Ann, Massachusetts. (See pp. 16-18 for Pringle’s affirmation of incorrect traditional interpretations of Algonquian place names.) Sources for the towns in the rest of Essex County include Edward Stone’s 1843 History of Beverly, Civil and Ecclesiastical, from its Settlement in 1630 to 1842; Joshua Coffin’s A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, from 1635 to 1845; Robert Crowell’s 1853 History of the Town of Essex, 1634-1700; Old Naumkeag: An Historical Sketch of the City of Salem, and the Towns of Marblehead, Peabody, Danvers, Wenham, Manchester, Topsfield, and Middleton by Carl Webber and Winfield Nevins (1877); D. F. Lamson’s 1895 History of the Town of Manchester, Essex County, Massachusetts 1645-1895; Joseph Felt’s Annals of Salem from Its first Settlement, Volume I (1845) and his History of Ipswich, Essex, and Manchester (1966); History of Lynn, Essex County, Massachusetts, including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott, and Nahant, 1628-1893, by Alonzo Lewis and James R. Newhall (1844); Sidney Perley’s The History of Boxford, Essex County, Massachusetts, from the Earliest Settlement Known to the Present Time (1880); John Currier’s 1902 History of Newbury, Mass. 1635-1902; and Thomas Waters’ 1905 Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. General sources for the history of Essex County include Hurd’s History of Essex County (1888); Benjamin Arrington’s Municipal history of Essex County in Massachusetts (1922); and Claude Feuss’ The Story of Essex County (1935). For information on Masconomet see the index to the Winthrop Papers, the Ipswich histories, and the Native American deeds in Essex County at the web site of the Southern Essex County Registry of Deeds (www.salemdeeds.com). See also Sidney Perley’s The Indian Land Titles of Essex County, Massachusetts (1912).

- John Smith’s 1624 version of his map of New England incorporates Algonquian place names he learned from an Abenaki sagamore in Maine. Earlier versions, such as his map of 1614 (published in 1616) do not. The 1624 map also shows the earliest English settlements, including Plimoth and Salem. These maps are compared in Chapter 4 of this book. See William Wood’s map. “The South part of New England as it is Planted this yeare, 1634” in Google Images or in Fite and Freeman, A Book of Old Maps Delineating American History, pp. 136-139. Robert Raymond’s enlarged detail of Wood’s map is at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~raymondfamily/WoodMap.html.

- Wood’s narrative description is in his New England’s Prospect (1635), pp. 31-38.

- In addition to the sources cited above on anthropological linguistics (Note 2), help reconstructing Pawtucket place names from the Abenaki came from Laura Redish, co-editor with Orrin Lewis of Native Languages of the Americas (2012) at http://www.native-languages.org; the Western Abenaki Dictionary and Radio Online at http://westernabenaki.com; and Cowasuck [Kowasek] Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People (the People of the White Pines) at http://www.cowasuck.org/language. A valuable historical source is Joseph Laurent’s 1884 New familiar Abenakis and English dialogues: the first ever published on the grammatical system, at http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.08895/5?r=0&s=1.

- Gloucester as Agamenticus appears on the website of the Massachusetts Citizen Information Service on the list of “Archaic Community, District, Neighborhood, Section, and Village Names in Massachusetts” (see www.sec.state.ma.us/cis/).

- The Pilgrim Roger Williams, the Puritan John Cotton, the Jesuit Father Rale (sometimes written as Rales or Rasle), the linguist R. Douglas-Lithgow, and others provided alternative etymologies for the state name of Massachusetts. See http://www.statesymbolsusa.org/Massachusetts/name_origin.html.

- Quascacunquen and Indian Hill both appear on a 1640 map of Newbury reproduced in John J. Currier’s History of Newbury, Massachusetts 1635-

1902 (1902). - John Josselyn, An Account of Two Voyages to New-England, p. 129. See http://archive.org/stream/accountoftwovoya00joss#page/n7/mode/2up.

- Dunton, John. 1686. Letters Written from New England. Prince Society Publications Issue 4, N. Stratford, NH: Ayer Publishing (1966 edition).

- Bright, William. 2004. Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Trumbull, J. Hammond. 1870. The Composition of Indian Geographical Names, Illustrated from the Algonkin Languages. Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainard: http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=1511626. See also 1897, IV. On the Best method of Studying Native American Languages; VIII. On Some Mistaken Notions of Algonkin Grammar, and on Mistranslations of Words from Eliot’s Bible; and VII. On Algonkian Names for Man. In American Philological Society Proceedings and Transactions, Vols. 1 and 2.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. 1839. Algic Researches (NY: Harper). (Algonquian languages are in the Algic Language Group.) See also Schoolcraft and Seth Eastman. 1855. Historical and statistical Information, respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Coll. and prepared under the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per act of Congress of March 3rd 1847. Volume 5: 221-224. New York, NY: Lippincott, Grambo.

- The document “The Names of the Rivers” was found in the British Library in the Egerton Mss 2395, “Papers Relating to the English Colonies in America and the West Indies, 1627-1699”, in British Records Relating to American History in Microform (BRRAM) Series (1974). It was among the papers of Thomas Povey (1613-1705) who was a secretary of Charles II. See “Thomas Povey Papers and Letters”, Egerton Mss #2395 Folio 412-213. The full title of the document is “Names of the Rivers and the names of ye cheife Sagamores yt inhabit upon Them from the River of Quibequissue to the River of Wenesquawam.” [i.e., from the Penobscot River to the Annisquam River”], n.d. Egerton Manuscripts 2395 (Fol. 412). An excellent review and analysis of this document is provided by Mary Beth Norton and Emerson W. Baker in “The Names of the Rivers: A new look at an old document.” New England Quarterly Vol. 80, No. 3: 459-487 (September 2007). For reference to a village in Riverview see Pool, Ebenezer. 1823. Pool Papers, Vol. I. Typescript Ms are in the Cape Ann Museum and the Sandy Bay Historical Society. (The original is in the basement of the Sandy Bay Historical Society in Rockport, MA).

- The 1890 Survey Plan for cottage lots in Winniahdin is in the Perkins Collection of historic maps and may be viewed at historicmapworks.com/Map/US/1573034/Winniahdin+1898+Annisquam+River++West+Gloucester+Station++Pequoit++Sonka/West+Gloucester+1890c+Survey+Plans/Massachusetts.

- E. N. Horsford’s comments on place names come from a paper he read before the New England Historic Genealogical Society on November 4, 1885 (pp. 16-17): “The Indian Names of Boston, and Their Meaning”.

- See Public Domain Review, Arnoldus Montanus’ New and Unknown World (Die Nieuwe en Onbekende Weereld, 1671) at http://publicdomainreview.org/. The map detail from Montanus’ Di Novi Belgi in De Nieuwe en Onbekende Weereld is from http://www.mapsofpa.com/17thcentury/1673montanuseast.jpg.

- Nobsten for lobster is an anecdote from Daniel Gookin referenced to James Davies’ Relation of a voyage to Sagadahoc, 1607-1608, reprinted by the Hakuyt Society in 1849 and the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1880. Davies was the navigator of Raleigh Gilbert’s vessel the Mary and John on a voyage to establish a colony on the Kennebec River in 1607 in an expeditionary fleet led by George Popham and financed by Sir Fernando Gorges and other backers. Monomack and the like for Merrimack is reported in J. William Wallace Tooker’s “The Significance of John Eliot’s Natick and the Name Merrimac” in The Algonquian Series (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1901).

- My proposed reconstruction of Wingaersheek as Winkawecheek was based on a word meaning for winga-/winka- proposed by Carol Dana of the Department of Cultural and Historic Preservation of the Penobscot (Penawahpskewi) Indian Nation on Indian Island, Maine, in 2011, based on her participation in a Western Abenaki language revival program. My sources for information on wampum and its use in systems of exchange appear in the notes for Chapter 10, which considers this topic in greater detail. Archaeological evidence for villages at Wingaersheek and Riverview in Gloucester comes from sites surveyed and excavated between 1920 and 1940, described in unpublished talks given by collector N. Carleton Phillips in 1940 and 1941 and stored in the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester. Discoveries at Wingaersheek in 1965 are preserved as the Matz Collection in the Harvard Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge, and more recently in Cultural Resource Management projects under the aegis of the Massachusetts Historical Commission in Boston. Other archaeological sites are cited in the notes to other chapters as relevant.

- Support for the definition of Pennacook used in this book (referring to groundnuts rather than foothills) comes from Gordon Day’s essays (Day, G. M. [1998]. M. K. Foster & W. Cowan [Eds.], In Search of New England’s Native Past: Selected Essays from Gordon M. Day.)

- Sources for Micmac (Mi’Kmaq) reconstructions in this work include Silas Rand’s Micmac Dictionary (1888) and the work on which it is based: A first reading book in the Micmac language: comprising the Micmac numerals, and the names of the different kinds of beasts, birds, fishes, trees, &c. of the maritime provinces of Canada. Also, some of the Indian names of places, and many familiar words and phrases, translated literally into English (1875). See also Rand’s “A Selection of Micmac Words” from The Micmac Dictionary (Halifax, 1888). In V. M. Marshall, “Silas Terius Rand and his Micmac Dictionary”, Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly 5 (4): 393. Another source is Elizabeth Frame’s List of Micmac Names of Places, Rivers, etc., in Nova Scotia (1892).

- For other examples of Native American, English, and French exonyms for tribes and nations, see http://www.native-languages.org/original.htm.

NEXT: Appendix: Pronunciation

Wonderful – thank you!