Human Migration to the Western Hemisphere

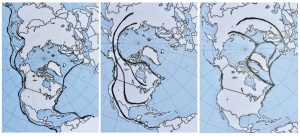

There are different theories and bodies of evidence about the succession of people occupying New England, with different views on where and when migrations occurred, as well as where and when people adapted culturally in place.[1] There is a huge literature on the subject, but this history takes the view that Ancient Northern Eurasians (ANE) first traversed New England from the north and east across the Arctic Circle and North Atlantic between 40 and 20 thousand years ago up to the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Marine Isotopic Stage 2). They were followed by people known as the Paleoindians, who came from the north and west as the last Ice Age was waning.[2] Migration routes included the North Pacific—the earliest migration route of humans into the Western Hemisphere—and may have also included the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, and North Atlantic. So, people were here much earlier than we thought, came at more than one time, and did not all arrive via the Bering Strait land bridge.[3] Recent discoveries and reinterpretations of evidence, as well as advances in the field of population genetics, suggest that the Western Hemisphere was populated through multiple migrations by different people with common ancestry at different times. Genetic evidence also suggests that people may have occupied the Mississippi Valley as early as 37,000 years ago or earlier.[4]

Migration Routes into the Western Hemisphere[5]

Changing Timelines

Thus, the time lines for Indigenous history in the Western Hemisphere continue to change. At one time the earliest occupation was judged to be 10,000 years ago, based on the appearance of Clovis tools in the East and “Western Stemmed” tool types in the West in the archaeological record. That date was referred to as the “Clovis Line” and very few archaeologists dared to cross it until very recently, when the sheer weight of new evidence made it impossible to ignore. That new evidence came from newly discovered or reinterpreted archaeological sites and the fields of population genetics, physical anthropology, paleoecology, and glaciology. The dates keep getting pushed back as irrefutable evidence for earlier occupation grows. The evidence comes from advances in the fields of geology (rocks), paleontology (fossils), archaeology (artifacts), genomics (genes), and laboratory science and technology (forensics). Clearly, other people were here prior to the Paleoindians.

Timeline of Archaeological Periods in New England[6]

| PERIOD | YEARS AGO |

| Pre-Clovis | ? — 14,500 |

| Paleoindian | 14,500 — 10,000 |

| Archaic | 10,000 — 3,500 |

| Woodland | 4,000 — 500 |

| Contact | 1,000 — 200 |

| Colonial | 500 — ? |

Timeline of Indigenous Peoples in Essex County

| PERIOD | YEARS AGO |

| Paleoindians | 12,500 — 10,000 |

| Maritime Archaics | 10,000 — 3,500 |

| Eastern Woodland Indians | 4,000 — 1,500 |

| Algonquians | 1,500 — Present |

Dating the sites of ancient people can be done by analyzing the chemical signatures of the charcoal in their fire pits, burned acorns or corn kernels, food residues in their pots, the depth of accumulation of their shells (from shellfish harvesting and refuse disposal), and the species of mollusks present in shell heaps. Shellfish species may be diagnostic of the time of occupancy, based, for example, on the proportions of oysters, surf clams, quahogs, soft-shelled clams, razor clams, mussels, whelks, and other land and sea snails. Sites with concentrations of large thick surf clams, for example, are earlier than sites with greater concentrations of soft-shelled clams. Sites with greater proportions of oyster shells point to times of comparatively warmer ocean temperatures and less saline waters. Sites are also dated by the isotopic makeup of bones and teeth, the evolutionary characteristics of plant and animal species, the succession of pottery and tool materials and styles, and comparisons of artifacts and features with dated remains from other sites.

Pre-Clovis People

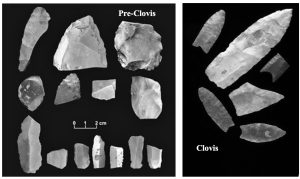

The archaeological designation of “Pre-Clovis” refers to the tools of the earliest people who preceded the Paleoindians, later immigrants famous for their “Clovis” style technologies. Pre-Clovis peoples from Asia traveled down the west coasts of the Americas, all the way to Tierra del Fuego, and then other Pre-Clovis peoples (referred to here as the ANEs) traveled down the east coasts of the Americas as far as Argentina. Pre-Clovis tools in the Americas are technologically similar to the tools of Upper Paleolithic peoples of Eurasia.[7] The oldest dated sites in the Western Hemisphere lie between 40°S and 40°N on both coasts.[8] To date there is no evidence of Pre-Clovis occupation of Cape Ann or New England. Our history begins with the Paleoindians, tundra-adapted hunters of mammoths, mastodons, and other giant mammals of the Late Pleistocene.[9] Clovis style tools of the Paleoindians are unique to the Americas. They include symmetrical points flaked edge-to-edge on both sides (bifacial) with channeled or fluted bases.[10]

Pre-Clovis versus Clovis Tools[11]. (Waters et al. 2011 and 2021. Used with permission.)

The Paleoindians

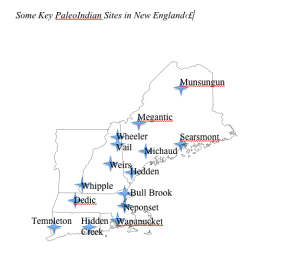

Paleoindian Clovis sites have greatest concentration east of the Mississippi River. A different contemporaneous Paleoindian tool tradition, called “Western Stemmed”, dominated west of the Mississippi.[12] Paleoindian sites have been found in every New England State, in the Ottawa Valley and all along the Merrimack River and its tributaries. In Massachusetts, Paleoindian sites and artifacts have also been found in Carver, Plymouth, Middleborough, Bridgewater, Raynham, Taunton, and Mansfield. Paleoindian people also gathered in large numbers on the Connecticut River, on Massachusetts Bay in Neponset, and on Narragansett Bay.[13]

Some Key Paleoindian sites in New England

After the last glacial maximum, the permafrost- and tundra-adapted Clovis culture spread explosively coast to coast and throughout the continent within 200 years. Paleoindian bands hunted megafaunal species, such as mammoths and mastodons, and tracked migrating herds of Pleistocene horses, camels, bison, and caribou. Fluted bifaces constituted a technological breakthrough. Countersunk in their shafts the doubly sharp points were more lethal and allowed for more efficient spearing with repeated stabs. If a point became lodged in the animal, a new spear point could be quickly loaded onto the same slotted shaft to replace it. As a consequence of rapid climate change at the end of the last Ice Age–sudden collapse of glaciers and catastrophic flooding throughout the Northern Hemisphere–the Clovis culture suddenly disappeared along with the megafauna the Paleoindians relied on, already scarce through over-predation. Survivors of the rapid environmental changes in New England were people who had relied on marine mammals instead. They were people of the Archaic Period.

Read more about the Paleoindians in Essex County

The Archaics

The people of the Archaic Period in New England adapted to climate change as the Paleoindians before them had done. As the last glacier retreated, the land rose, relieved of the glacier’s great weight. Huge glacial lakes from icemelt drained into basins and flooded river valleys. At the same time, sea level rose, drowning the mouths of rivers, creating estuaries as the coastline was revealed and salt water from the sea mixed with fresh water. Coniferous forests and grasslands expanded where once was only tundra, and the fauna and flora changed. Boreal forests on outflow plains (evergreens with grassy floodplains and territorial big game) replaced the tundra (treeless permafrost with willow shrubs, mastodons, and migrating herds).

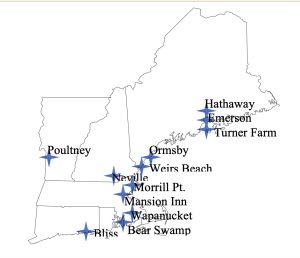

Some Key Archaic Period Sites in New England

The land continued to rise, warm, and dry, as it still is today, and the flora and fauna changed again. Mixed deciduous forests and prairies such as we have today arose and spread where once only evergreens grew, and a greater diversity of plants and non-migratory animals flourished in the new forests. People adapted to these changes at the same time as they adapted to the newly exposed and evolving shorelines. In the Northeast the earliest Archaics lived on the coast among the rocks from Newfoundland to Nantucket and specialized in marine mammals and fish for subsistence. Their descendants invented spear-throwers (atlatls) and discovered shellfish.[14]

Read more about the Archaic people in Essex County

Read more about the Archaic people in Essex County

The Eastern Woodland People

The Terminal/Transitional Archaic-Early Woodland Period in New England began around 3,500 years ago. The period was marked by changes in subsistence from year-round maritime adaptations to seasonal exploitation of diverse food resources in the spreading mixed-deciduous forests, along with a greater reliance on shellfish. People adapted to living on rivers in the new forests with seasonal migrations and forays among nearby biomes: freshwater swamps, cranberry bogs, beaver meadows, lakes and ponds, estuaries with clam flats and mussel shoals, and the saltmarsh and forest haunts of resident deer and other game.

Indigenous warriors with bows and arrows in Virginia, 1590[15]

Woodland people diversified regionally–Great Lakes, Southeast, Northeast, for example–developing different families of languages and cultural traditions. The period is also marked by the introduction of new or enhanced technologies. The bow and arrow with smaller projectile points and greater range, perfect for hunting in the woods, replaced the spear thrower for hunting in open spaces, and the Woodland people developed canoe making, weaving and basketry, and pottery making. In Maine, the period following the Maritime Archaic is referred to as the Ceramic Period.

Most significantly, while Archaic people had cultivated and possibly domesticated local wild food plants, such as the chenopodiums (the so-called goosefoots, including lamb’s ears, amaranth, and quinoa), Late Woodland people brought intensive horticulture and agriculture to New England via the Mississippi, Ottawa, Ohio, and Susquehanna valleys as early as 1,500 years ago. In northern New England life centered on hunting and gathering, while in southern New England Woodland life came to center on fishing, forest management, and farming–mass producing maize (corn).[16]

Some Key Woodland Period Sites in New England

Read more about: Who were the people of the Eastern Woodlands

The Algonquians

Woodland Indians in the Northeast, the Great Lakes region, the northern Plains, and much of Canada spoke Algonquian (Algic), Iroquoian, or Siouan languages, and are respectively known historically as the Algonquians, Iroquois, or Sioux. Within each language family, linguistic and cultural distinctions developed between different bands, tribes, and nations, many of which continue to exist today.

Diversification of Eastern Woodland Peoples in the Northeast

Diverse Algonquian people of the Northeast include, for example, the Pennacook (including the Pawtucket), Nipmuc, Abenaki, Penobscot (Panawahpskewi), Massachuset, Mahican, Lenape (Delaware), Powhatan, Ojibwa, and others.

During the Late Woodland Period, prior to European contact, Algonquian-speaking peoples were connected in trading networks that spanned from Canada to Virginia and westward to the Great Lakes and headwaters of the Mississippi River. Trading networks developed through systems of alliance, intermarriage, and special dialects for trade (argots or patois or pidgins used by people speaking different languages to negotiate exchanges). The Algonquians traded shells and shell beads, pearls, dried fish and seafood, furs, and ores and minerals to people of the interior as far as the Great Lakes in exchange for flints and other sedimentary stones, copper, seeds, and medicinal herbs such as sage. They traded dried corn and tobacco to the north for furs and later traded furs for European trade goods as far as Tadoussac (the first French trading post, east of Quebec at the junction of the St. Lawrence and Saguenay rivers) and with the Dutch near Albany and present-day Hartford. Prior to Contact, New England Algonquians also traded birchbark and pine tar for plant dyes and tobacco with Algonquians to their south as far as Chesapeake Bay.

The Eastern Algonquians, stretching along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia to Virginia, were the first to experience European contact. Many Eastern Algonquian peoples have origin stories explaining how they were the first or most ancient people to occupy the Atlantic seaboard. The Algonquian names Wabenaki (Maine) and Lenni Lenape (Delaware), and others, translate to “people of the dawn” and “the first people” or “people of the Dawnland”. Surviving Indigenous place names in New England and throughout the Northeast come from Algonquian languages. So how were Algonquians making their living in Essex County at the time of European contact?

NEXT: How did Eastern Algonquians make their living in Essex County?

Notes and References

[1] For more on this subject, see my article, Migration to the Americas: Making Sense of Multiple Routes, in the Journal of the New England Antiquities Research Association 54 (1), Fall 2021.

[2] The ANE (Ancient Northern Eurasian) and AP (Ancient Paleo-Siberian) designations come from Russian scholars working on the problem of human migrations to the Americas. See, for example, Sikora, Martin, et al., 2018, Ancient genomes show social and reproductive behavior of early Upper Paleolithic foragers. Science 360 (6387): eaao1807.

[3] Erlandson, J. M., M.H. Graham, B.J. Bourque, D. Corbett, J.A. Ester, and R. 2007. The Kelp Highway Hypothesis: marine ecology, the coastal migration theory, and the peopling of the Americas. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 2: 161-174. Goebel, Ted, Michael R. Waters, and Dennis H. O’Rourke. 2008. The Late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science 319 (5869): 1497-1502.

Hoffecker, J.F., S.A. Elias, and D.H. O’Rourke. 2014. Out of Beringia? Science 343: 979-980.

Jodry, M. 2014. New Evidence for Paleolithic Occupation of the Eastern North American Outer Continental Shelf at the Last Glacial Maximum. Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf, New York, Springer, pp. 73-94. Stephan Schiffels, and Todd A. Surovell. 2018. Current evidence allows multiple models for the peopling of the Americas. Science Advances 4 (8): eaat5473.

[4]I support the view that Pre-Clovis people arrived both overland from the west and across the Arctic Circle and by sea routes down both coasts. An example of evidence from genetics is a theory advanced by Theodore Schurr that migration occurred between the southern Caucasus or Altai region of Central Asia and northeastern North America between 35,000 and 13,000 years ago by people carrying human haplotype X, a founding mitochondrial haplotype. Haplotype X is present in Siberia today and makes up 25 percent of mtDNA in people of Algonquian descent, especially Canadian Ojibwa, Chippewa, and Cree. Read Schurr’s article at www.sas.upenn.edu/~tgschurr/pdf/Am%20Sci%20Article%202000.pdf. Evidence from nuclear DNA (yDNA) shows high coincidences of haplogroups R1, Q, and C3 in Native Americans and Siberians, especially among speakers of Na-Dene, Algonquian, and Central Asian languages, with a reconstructed language origin in the southern Altai Mountains. See, for example, Martin Lewis’s 2012 article in GeoCurrents at http://www.geocurrents.info/place/russia-ukraine-and-caucasus/siberia/siberian-genetics-native-americans-and-the-altai-connection. See also O’Rourke D.H. and J.A. Raff. 2010. The Human Genetic History of the Americas: The Final Frontier. Current Biology 20 (4): R202-R207; Raghavan M., M. Steinrücken, K. Harris, S. Schiffels, S. Rasmussen, M. DeGiorgio, A. Albrechtsen, C. Valdiosera, M.C. Ávila-Arcos, and A-S. Malaspinas. 2015. Genomic evidence for the Pleistocene and recent population history of Native Americans. Science 349 (6250). The evolutionary genetics of animal and plant remains also aids in interpreting and dating archaeological sites. An example is determining if remains represented a domesticated or wild species, as in a 2012 study by Larsen, et al. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(23): 8878-8883): http://www.pnas.org/content/109/23/8878.

[5] These original illustrations come from my 2021 article, Making Sense of Human Migration to the Americas, in the NEARA Journal (Journal of the New England Antiquities Research Association) 54 (1): 22-45. The earliest migration, prior to the last glacial maximum, was down both coasts. The second, most massive, migration was via Beringia as the last ice age was ending, spreading west to east across the continent; and the third, most recent, migration was across the Arctic. The ancestral population of all three migrations had a common origin in the Altai region of western Asia.

[6] Archaeological periods all have early, middle, and late phases, vary regionally, and are not mutually exclusive. The record shows conservatism in tool types and styles, such that, once established, many carry over from period to period. Confidence in dating varies according to the method of dating and the accurate calibration of dates based on radiocarbon measurements. Without comparable verified absolute dates, time lines and time charts are always imperfect. Dates also vary by the particular kinds of sites being dated, the systems used for classifying artifacts, the quality of the samples being dated, and the theoretical orientations of the scientists doing the dating. Dates also constantly change as new evidence is unearthed or better methods of testing are developed. At one time it was thought the Western Hemisphere was not occupied until around 10,000 years ago, for example, but now we have confirmed dates of four times that age and more. Time periods and dating methods used in archaeology also vary internationally, but the Paleolithic, Archaic, Woodland, and Contact periods are standard for North America. For basic information on dating methods, see Michael G. Lamoureaux’s web site (2009): The various dating techniques available to archaeologists, at http://www.sourcinginnovation.com/archaeology/Arch08.htm, and the 1997 Taylor and Aitken text, Chronometric Dating in Archaeology. For more technical information, see also Barnard and Eerkens’ 2007 book, Theory and Practice of Archaeology Residue Analysis from Archaeopress. The dates in this chronology are based partly on William S. Fowler’s classic work, revised in 1991, A Handbook of Indian Artifacts from Southern New England, Massachusetts Archaeological Society Special Publication 4, p. 6, combined with actual dates recalibrated from radiocarbon dates at http://archnet.asu.edu/archives/regions/northeast/culthist/cttime.htm, which, in turn, are based on National Park Service data for the southeastern United States: http://www.nps.gov/archeology/pubs/nhleam/E-Introduction.htm. Updated chronologies for New England tend to agree, give or take a mere 250 to 500 years for any given span of time in a period.

[7] See, for example, Michael R. Waters 2011 article, Pre-Clovis Mastodon Hunting 13,800 years ago at the Manis kill site, in Science 334: 351-353 and Goodyear, Albert C. 2005. Evidence of Pre-Clovis Sites in the Eastern United States. Paleoamerican Origins: Beyond Clovis: 103-112.

[8] See, for example, Bourgeon, Lauriane, Ariane Burke and Thomas Higham. 2017 (6 January). Earliest human presence in North America dated to the Last Glacial Maximum: New radiocarbon dates from Bluefish Caves, Canada. PLoS ONE 12 (1): e0169486. It is irrefutable that people occupied North America in waves way before 10,000 BC (12,000 years ago); yet some Americanists still cling to the traditional date of 10,000 BC for Paleoindian arrival in North America. This date is called the Clovis Line after the type of stone tools identified with that time, originally found in Clovis, New Mexico. New finds, advances in radiocarbon dating, and new dating methods place the occupation of all parts of the Western Hemisphere much earlier in time than 10,000 BC, however, by people with Upper Paleolithic tools such as Gravettian rather than with Clovis tools. Texts that claim “Clovis First” or cite the “Clovis Line” and do not refer to Pre-Clovis people are badly outdated.

[9] E.g., Madsen, David B. 2015. A Framework for the Initial Occupation of the Americas. Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281005047_A_Framework_for_the_Initial_Occupation_of_the_Americas; Spiess, Arthur E., Deborah Brush Wilson, and James Bradley. 1998. Paleoindian Occupation in the New England-Maritimes Region: Beyond Cultural Ecology. Archaeology of Eastern North America 26: 201-264.

[10] To see the different types of Clovis points used in Paleoindian times in New England, see Jeff Bourdeau’s A New England Typology Native American Projectile Points (2008). For a perspective on Paleoindian source stone and what it can tell us about people’s movements and associations, see Adrian Burke’s Paleoindian ranges in northeastern North America based on lithic raw materials sourcing (2004) at http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr/documents/08burke.pdf.

[11] Waters, M. R., Forman, S. L., Jennings, T. A., Nordt, L. C., Driese, S. G., Feinberg, J. M., Keene, J. L., Halligan, J., Lindquist, A., Pierson, J., Hallmark, C. T., Collins, M. B., and Wiederhold, J. B., 2011, The Buttermilk Creek Complex and the Origins of Clovis at the Debra L. Friedkin Site, Texas. Science, v. 331, p. 1599-1603. See also Waters et al, 2021, The Age of Clovis: 13,050 to 12,750 cal yr B. P. in Science Advances 4 (43).

[12] See Michael Faught et al. and the Paleoindian Database of the Americas web site, updated in 2005 by D.G. Anderson, at pidba.org. This database shows the classification of Paleoindian projectile points and their geographic distribution. The Paleoindian sites identified in this chapter and the map showing the concentration of fluted points east of the Mississippi come from this source.

[13]There are numerous reports of specific Paleoindian sites in the northeast. See, for example, Spiess and Bradley (1996): Four “Isolated” fluted points from the lower Merrimack River Valley of northeastern Massachusetts, in Archaeology of Eastern North America 24, and Bradley (2007): PaleoIndian Sites and Finds in the Lower Merrimac River Drainage, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 68 (1).

[14] I support the view that during the Archaic Period two-way north-south migration along the eastern seaboard took place, accounting for the presence of tool types characteristic of people from the Middle Atlantic coast as well as from the coasts of northern New England and the Canadian Maritimes. My principal sources for the Early Archaic period come from Joseph Belanger (2008), The Early Archaic Period in New Hampshire: A Review of the Literature, in The New Hampshire Archaeologist 48 (1), David Sanger (1988), Maritime Adaptations in the Gulf of Maine, in Archaeology of Eastern North America 16, and Bruce Bourque (2012), The Swordfish Hunters: The history and ecology of an ancient American sea people. Descendants of the Marine Archaics in the north are thought to have been the ancient ancestors of the Thule, whom the Vikings encountered in Greenland in the 11th century; the Beothuk, whom Jacques Cartier encountered in Newfoundland in the 16th century; and the Inuit, or Esquimaux as the 17th century French explorers called them.

[15] John White drew these Eastern Woodland Indians with bows and arrows on Chesapeake Bay in 1585. White’s 19 surviving paintings of indigenous people were popularized through colorized etchings by Theodore de Bry. See https://benjaminpbreen.com/2012/04/30/images-of-a-new-world-the-watercolors-of-john-white/.

[16] Because archaeologists specialize, general sources on the Woodland Period and Eastern Woodland Indians are rare, other than books for children. My preferred primary sources on Native life in the Late Woodland Period as reflected in Contact Period contexts include Thomas Hariot (1585), John White (1585), Samuel de Champlain (1604-1610 [Otis Vol. II 1878]), Edward Winslow (1624), William Wood (1634), Thomas Morton (1637), Roger Williams (1643), Edward Johnson (1654), John Josselyn (1674), and Daniel Gookin (1674). Kathleen Bragdon’s Native People of Southern New England 1500-1650 (1999) is a good secondary source for the Late Woodland and Contact periods.