The Coastal Villages

The places the English called Agawam, Chebacco, Wingaersheek, and Wonasquam describe different portions of eastern Essex County and originated as Abenaki-based Algonquian place names. The place names originally referred to villages rather than sovereign territories, but were expanded by the English to describe putative tribal territories.1 Thus “Agawam”, in addition to being the name of a principal village, was the name given to the area between the Merrimack River and Salem Harbor within the jurisdiction of the sagamoreship led by Masconomet/Masquenominet at the time of contact. This wider area encompassed the shores and fresh and salt marshes of the estuaries and bays of the Annisquam, Essex, Ipswich, Rowley, and Parker rivers and their tributaries–the Great Marsh–as well as Plum Island and Plum Island Sound.

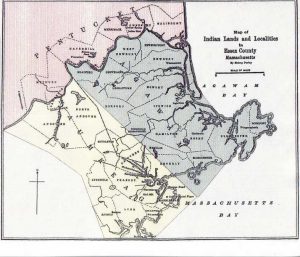

Perley’s Map of Indian Lands

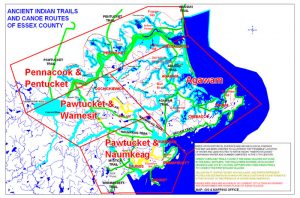

Sidney Perley’s 1912 Map of Indian Lands, based on colonial records, shows three divisions of Indian territory in Essex County: Pentucket, with a principal village at Haverhill, was “at the bend in the big tidal river”, referring to the Merrimack where it bends to the east after its junction with the Concord River to its south; Agawam, including Cape Ann, was “beyond the marsh” or “other side of the marsh” along the shore; and Naumkeag (Nahumkeak) encompassed Beverly, Peabody, Middleton, Danvers, Salem, and Marblehead.2

The three regions on Perley’s map were all occupied by the Pawtucket in common tenancy. It was a misconception of colonial observers that these were discrete sovereign territories. There actually were no Pawtucket tribes. Place names named only rivers and the villages upon them and by extension the sagamoreships occupying them. The English interpreted those names within their own political frame of reference to mean sovereign tribes or nations, and referred to the native leaders as chiefs or kings. A sagamore, however, was a chosen member of an alpha lineage or high-status family, the group leader and representative of a shared lineage, identified as a sacred ancestor in the form of a spirit or animal totem. Eligibility for sagamoreship was largely inherited. A sachem was the chosen leader of several related or confederated sagamoreships or bands. Thus the two terms, sachem and sagamore, were not synonymous as is sometimes claimed or assumed. Pawtucket social organization is explored in greater detail in another context.

As noted previously, prior to contact by 500 to 750 years or more, the people had permanent and semi-permanent agricultural settlements on uplands associated with the estuaries of the rivers emptying into Ipswich Bay. Large Pawtucket coastal agricultural villages attested in early accounts as occupied at the time of first contact included Quascacunquen (Kwaskwaikikwen, Old Town Hill, West Newbury), Agawam (Town Hill, Ipswich), Wenesquawam (Wanaskwiwam, Riverview, Gloucester), and Naumkeag (Nahumkeak, Salem-Beverly).3

Coastal Villages on Ipswich Bay

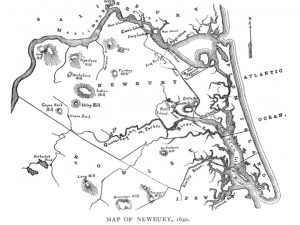

Quascacunquen, for example, is preserved as the name of the Parker River in a 1640 map of Newbury, which also identifies Indian Hill at the headwaters of the Artichoke River.4

1640 Map of Newbury Showing the Parker River as Quascacunquen River and the locations of Old Town Hill and Indian Hill

Knowledge about the exact location of Agawam Village has long been suppressed, raising questions about a conflict between the public’s right to know local history and stewards’ needs to protect sites from looting and desecration. In addition, some homeowners conceal finds on their property in the mistaken belief that disclosing them would somehow result in loss of property (or construction of a casino). An underworld exists of unscrupulous collectors who would not hesitate to desecrate a grave to find objects to sell in online stores. Today, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act serves to protect burial sites and sacred objects, but the state has extended secrecy about Native sites to the extent that residents did not know there were ever any Native Americans living on Cape Ann!5 Site reports of Cultural Resource Management (CRM) archaeological studies are sequestered in the Massachusetts Historical Commission’s closed archives and are not made public knowledge.6

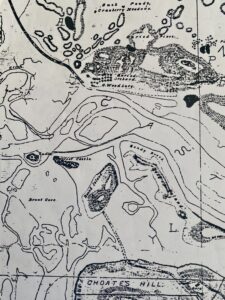

Le Baron’s 1874 archaeological map shows the location of archaeological sites on Great Neck, at Wigwam Hill on Castle Neck “on the other side of the marsh” and along the Ipswich River. The main settlement of Agawam Village was on present-day Town Hill. Its neighborhoods included Wigwam Hill, Argilla Road, Fox Creek, Labor-in-Vain Creek, and the islands of Essex bay.7 Le Baron’s map also shows the location of Masconomet’s forts on Town Hill and on Round Island in the Little Castle Neck River. The island fort was named Great Castle.8

.

.

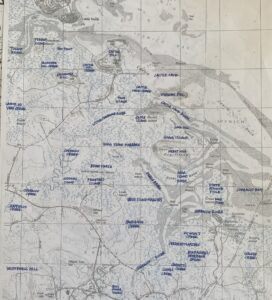

This map shows Sagamore Hill in Ipswich (present-day Town Hill) in an unpublished historical map by Tod Beddall, used with permission.

In July 2023 I received new information from the researcher Tom Beddall, a long-time volunteer on the Crane Estate for the Trustees of Reservations. The information comes from his maps and deeds research and includes an unpublished letter of 1906 from the archaeologist Francis LeBaron to the Ipswich historian Thomas Waters, and a 4-color reproduction of the original LeBaron map (I was working from a black and white copy). Additional references include the “Essex” section by John Prince in Volume 2 of D. Hamilton Hurd’s 1888 History of Essex County: https://www.loc.gov/item/01012171/.

While Pawtucket families were living at Wigwam Hill on Castle Neck, a larger settlement and Masconomet’s main residence was located at Sagamore Hill in Ipswich. This was a different Sagamore Hill than the Sagamore Hill in South Hamilton today, just three miles away from the original Sagamore Hill, where Masconomet and his family are in fact buried. The original Sagamore Hill in Ipswich was later renamed Town Hill and remains Town Hill today. Town Hill was the center of Agawam Village, which had widely distributed family settlements all around it. The Ipswich Sagamore hill has a sightline to Great Neck and the mouth of the Ipswich River and Labor-in-Vain Creek, and this is where the Pawtucket were attacked by Tarrantines in 1631.

In 1631 and 1632 the Massachusetts Bay Colony sent John Winthrop Jr. and eleven other men from Charlestown to Agawam to assess the area for a plantation, to evict English squatters—those who bought land directly from the Indians and were living there before the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—and to discourage settlement by the French, who were establishing fur trading posts along the coast. The Winthrop party helped Masconomet repel deadly the Tarrantine attack in 1631 and at other times on his forts at Sagamore (Town) Hill and at Great Castle on Round Island. These forts guarded the entrances to Labor-in-Vain Creek from the Ipswich River and Fox Creek from the Little Castle Neck River. These were the access routes by canoe to the Pawtucket cornfields on Argilla Road.9 Tarrantine corn raiders came from Nova Scotia and settlements on the Bay of Fundy down through the Gulf of Maine to Casco Bay and until around 1635 affected Algonquian coastal farmers all the way from New Hampshire to Nantucket.

In addition to Wigwam Hill and Sagamore Hill in Ipswich, Pawtucket families were also living on the east flank of Castle Hill, the southwest side of Choate Island, Cross Island in Essex Bay, both banks of the Chebacco River in Essex (including Cogwsell’s Grant), along Argilla Road in Ipswich where they had their cornfields, on the Ipswich River under the present-day town of Ipswich, and on Great Neck. (Prior to 1630 Great Neck was known as Jeffreys Neck, William Jeffreys having been a “squatter” from Plymouth Colony who had bought the land–and a fishing bank offshore known as Jeffreys Ledge–directly from Masconomet prior to the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Jeffreys also bought Pawtucket land along the coast of Magnolia, Kettle Cove, and Manchester-by-the-Sea, which he called Jeffreys Creek.)

“Agawam” in Ipswich referred mainly to the area between Labor-in-Vain Creek where it joins the Ipswich River and the Essex River, known then as the Chebacco River, with its name changing to Little Chebacco River, and then Chebacco Creek where it enters the marsh. As noted, when John Winthrop arrived to govern the newly created Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, he sent his son John Winthrop Jr. to evict English squatters living on Heartbreak Hill and eking out a living attempting to farm on Labor-in-Vain Creek. The squatters (including Jeffreys) lost their holdings; hence the “labor in vain” and “heartbreak” place names.

The map above also shows the location of Town Hill in Ipswich (Masconomet’s home and the administrative center of Agawam Village), Castle Hill, where he conducted diplomacy, Sagamore Hill in S. Hamilton, where he retired and is buried, and Heartbreak Hill, where English squatters were evicted by the Mass. Bay Colony.

Defensive Networks

Pawtucket defensive positions on the sea consisted of lookout towers and forts that guarded against raids from the east by the Tarrantines of Nova Scotia and the Canadian Maritimes—Mi’Kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and sometimes Penobscot. They raided their southern neighbors for corn, which would not grow reliably at their latitudes.10 To the English colonists the wooden forts of the natives resembled medieval castles, with moats, ramparts, turrets, and parapets for dumping stones down on attackers—described in detail by Edward Winslow in 1621 on a visit to Naumkeag.11 The English called native forts “castles”, and there are sites all up and down the coast bearing place names with the word castle in them. There are several instances of Castle Hill, Old Castle, Castle Point, Castleview, Great Castle, and Castle Island, for example, from Maine to Maryland. In each locality, it is likely that an Indigenous fort guarded a river entrance, ringed with strategically placed watchtowers.

In 1634, Masquenominet complained to the Massachusetts General Court that Charlestown’s hogs were destroying Indian corn, and the Court decreed in 1636 that hogs had to be kept fenced or impounded on islands.12 In 1637, following another Tarrantine attack in which colonists helped to defend him, and following the Pequot War in Connecticut, in gratitude Masquenominet signed a deed granting his farmland between Chebacco Creek and Labor in Vain Creek (known historically as Argilla Farm) to John Winthrop Jr.13 Then in 1638 Masquenominet signed another deed granting Winthrop all the rest of Greater Agawam for the establishment of the English colony of Ipswich. In that deed “Agawam” extends from the Merrimack River to the Saugus River, and from the Concord River on the west to Cape Ann on the east and Salem on the south.14

Masconomet’s First Deed, readable on Salem Registry of Deeds web site.

In 1700, with the aid of magistrates Joseph Foster and Moses Parker, Masquenominet’s grandchildren filed suit in the Mass Bay Colony General Court against Gloucester and other towns in an effort to receive final installments on sections of land Masquenominet had originally sold to them in aggregate. They won their case, and the General Court ordered Gloucester to pay a final installment in cash in the amount of £7 to Masquenominet’s heirs in exchange for clear legal title to Gloucester and Essex. The heirs included Samuel English and his wife Susannah, Joseph English, John Umpee, and Jeremiah Wauches and his wife Bettey.15 Interestingly, Gloucester’s official history does not mention the facts of this case, only that in 1701 Samuel English redeeded 10,000 acres to Gloucester for £7. Other towns, such as Wenham, countersued in the Mass. Supreme Judicial Court, claiming that their original Indian deed was valid, and lost.16

1700/1701 Deed to Cape Ann (Gloucester, Rockport, Essex), readable on Salem Registry of Deeds website.

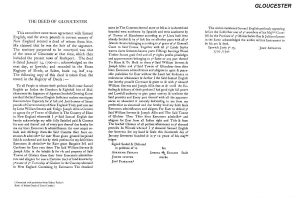

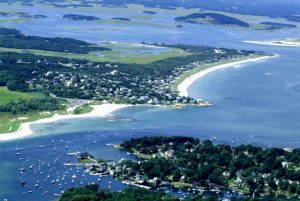

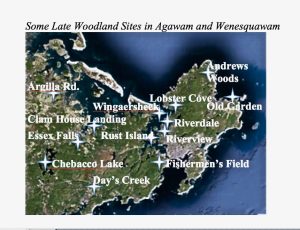

As noted previously, the part of Greater Agawam called Wenesquawam (Wanaskwiwam), which Josselyn and others referred to as Wonasquam, included a village by that name in Riverview on the Annisquam River as well as the region of present-day Gloucester and Rockport, inclusive of the river islands, harbor and back shore, Rocky Neck, Eastern Point, Riverdale, Annisquam, Bay View, Lanesville, Dogtown, Andrews Point, Pigeon Cove, Old Garden, Land’s End, Good Harbor, East Goucester, West Gloucester, and other neighborhoods. The area called Wingaersheek (Wingawecheek) included a settlement on the Jones River Saltmarsh, incorporating the dunes of the beach by that name as well as Coffin’s Beach and the islands on the eastern shores of Essex Bay, such as Cole’s Island.17

Location of Wanaskwiwam in Riverview

Location of Wingawecheek

Location of Wingawecheek

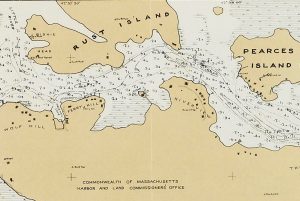

Based on archaeological evidence, especially the excavations of N. Carleton Phillips and Frank Speck, Wanaskwiwam was in Riverview near Curtis Cove just north of Pole Hill.18 Families also occupied campsites on the river islands (Rust Island and Pearce Island in particular), Planter’s Neck overlooking Lobster Cove in Annisquam, Fishermen’s Field on the harbor (as shown on Champlain’s map), and on other coves ringing the cape. Native planting grounds—for maize cultivation requires frequent shifting to new ground with fresh soil—would have been, for example, in Gloucester’s Riverdale on Mill River, along Cherry St., above Old Garden Beach in Sandy Bay, and behind Wingaersheek Beach along Atlantic St. Families also occupied resource procurement sites in West Gloucester on Little River and Jones River and on the islands of Essex Bay. The Pawtucket were growing corn at these sites. John Endecott purchased “hoed ground” from the Indians on Cape Ann.19 Settlers of Gloaster Plantation gave the name Cornhill Street to what was later named Middle Street20

As explained in an earlier section, the earliest documentary evidence for Wanaskwiwam is as Wenesquawam in the Egerton Manuscript in the British Library, an anonymous explorer’s account pre-dating 1610 entitled “Ye Names of Ye Rivers and Ye Sagamores Yte Inhabit Upon Them”. The name Wonasquam is later attested in Capt. John Smith’s 1624 map of New England, William Wood’s 1635 map, and John Josselyn’s accounts of his voyages to New England.21 Documentary evidence for an Indian village by that name is also found in the travel journal of John Dunton, a London bookseller scouting out the new American market for his wares.22 Dunton wrote in 1686 that he took a trip from Ipswich to Gloucester to see an Indian village called Wonasquam, which he reported to be in grave decline. He wrote in his letter:

After a long and difficult ramble [on the Agawam Trail from Ipswich to Gloucester, led by native guides], we came at last to the Indian town call’d Wonasquam. It is a very sorry sort of town, but better to come to it by land instead of by water, for ‘tis a dangerous place to sail by, especially in stormy weather.23

During his visit, Dunton encountered natives wearing the black facepaint of mourning and claims to have attended a funeral and ritual burial in honor of a very important but unidentified sagamore near Wonasquam Village. His description of funeral rites is similar to one written decades earlier by the Rhode Island colonial governor Roger Williams, who had witnessed an Algonquian burial in Agawam. It has been suggested that Dunton plagiarized Williams’ account, but nothing else in his journal points to any desire to sensationalize his travel experiences, and it would not be unusual for two descriptions of the same ceremony or ritual to be similar.24

There may well have been a mourning ceremony in Wonasquam in 1686 when Dunton was there. That was the year Wonalancet, Passaconaway’s son, died and Passaconaway’s grandson Kancamagus sold the last of the Pennacook homelands to the English. Passaconaway had famously and peacefully led a confederacy of Pennacook-Abenaki bands and tribes, including the Pawtucket of Wamesit and Agawam, from the beginning of the Contact Period to around 1669. John Owufsumug also died in 1686—the son-in-law of Sagamore George, the youngest son of the famous sachem Nanepashemet, who had led the Pawtucket, Nipmuc, and others prior to English settlement.25 Another loss that year was Daniel Gookin, the first government Indian agent of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and champion of the New England Indians. It is reported that he was widely mourned by Native Americans, who wore black face paint for him. They knew that without Gookin they would no longer receive government protection from the English.26

Algonquian Funeral as Described by Roger Williams: The mourning family places the body on the right side in a flexed position. The deceased is covered in a mat and interred with grave goods. A shaman (under the sacred oak) officiates.

Algonquian Funeral as Described by Roger Williams: The mourning family places the body on the right side in a flexed position. The deceased is covered in a mat and interred with grave goods. A shaman (under the sacred oak) officiates.

Anecdotal evidence for a village in Gloucester is also found in the papers of Ebenezer Pool of Rockport, who in 1823 recorded his grandfather’s and great grandfather’s stories about an Indian village of 20 to 30 wigwams just north of Pole Hill (Huckleberry Hill on early maps) in Riverview.27 A village of that size would have had a population of between 100 and 300 individuals. Pool also wrote about the practice early colonists had of paying for land in kind in installments, mainly with bushels of Indian corn. There is a record of sale of the last Pawtucket lands on Cape Ann in 1684 in exchange for Indian corn and other commodities.28

Ceremonial Gathering Places

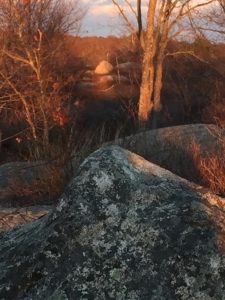

The existence of a Native village in Riverview is also supported by the discovery in 2013 by the author of a Native astronomical observatory and ceremonial landscape on Pole Hill. The site, still under investigation, has boulder alignments for the solstices and equinoxes dating to between 2,000 and 4,000 years ago.29 Observation posts for lunar standstills and the rising and setting of some bright stars and key constellations remain to be confirmed. The Algonquians were skywatchers. Villages were sited near places where shamans could observe the sun, moon, stars, and other celestial events.30

Summer Solstice Sunset Winter Solstice Sunset

Pole Hill with Wanaskwiwam Beyond Some Sightlines

Like Agawam, Wanaskwiwam also would have had defensive fortifications. On Cape Ann the most likely locations of Native watchtowers and forts would have included Squam Rock and Wigwam Point in Annisquam with their sightlines to the narrow, barred, entrance of the Annisquam River. Governor’s Hill overlooking Gloucester harbor and the sea beyond was originally called Castle Hill and then Lookout Hill before its name was changed first to Beacon Pole Hill and then to Governor’s Hill.31 Fortifications at Folly Point and the “Old Castle” site in Pigeon Cove would have protected Pawtucket living on Sandy Bay from the eastern enemies.

Kinship Networks

The Algonquians of Essex County, though widely dispersed as seasonally migrating bands, were connected with one another when they came together at their agricultural and winter villages as well as through marriage, transportation and trade, a tradition of pilgrimage, and mutual defense. All the people who distributed themselves among the river drainage systems on which life depended were connected through band exogamy, for example—a marriage rule in which women marry out of their groups and move into their husbands’ bands.32 The bands were all deeply interrelated through a millennium or more of intermarriage. The Pennacook-Pawtucket were interrelated with Nipmuc, Massachuset, and Abenaki people. The Pawtucket of Essex County and other eastern Algonquians thus had kinsmen all up and down the coast. The very first native person the Mayflower Pilgrims met in Plymouth in 1620, for instance, was an Abenaki sagamore from Pemaquid, Maine, on pilgrimage, who, to everyone’s astonishment, spoke English. Samoset had learned English through encounters with men of the English fishing fleets coming seasonally to Monhegan Island and Casco Bay in Maine.33 Those encounters predated the Pilgrims in New England by around 50 years.

Transportation Networks

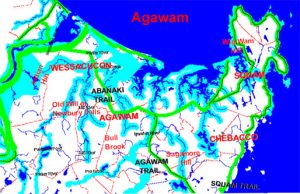

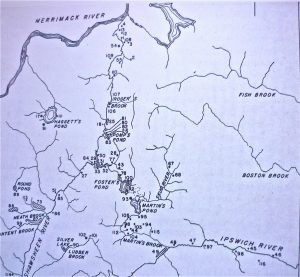

As noted previously, Algonquians also were connected by an extensive system of canoe routes, portages, and trails that joined coastal and inland villages. In Essex County, trails on land included the Mystick Trail to Boston, Naumkeag Trail between Andover and Salem, Abenaki Trail to Maine, Pennacook Trail to New Hampshire and Canada, Agawam Trail between Salem and Ipswich, Squam Trail connecting Cape Ann to Salem and Ipswich, and the Wamesit Trail between Salem and Lowell. Pawtucket transportation in and around Agawam and Naumkeag and trade routes to the interior and the north, as well as warpaths, followed these trails.34 Routes 127, 1A, 133, 22, 97, and 62 began as Indian trails.35

Native American Trails of Essex County

Pawtucket Trails in Agawam

Travel was by canoe wherever possible. Cape Ann is at the southern limit of birchbark canoe culture, with dugout canoes predominating further south.36 To reduce the number of portages and to protect Agawam transportation routes from exposure to the open sea, the Pawtucket cut canals between rivers and across the marshes to create an inland waterway behind Plum Island. A 3-kilometer channel through the saltmarsh connected the mouth of the Merrimack River to Plum Island Sound, for example, and another connected Essex Bay to the Jones River and thence the Annisquam River. Native canal building was reported anecdotally by Ipswich and Newbury colonists, who attempted to maintain the inland waterways for a time.37

The Pawtucket also built causeways to connect inshore and river islands to the mainland. Champlain’s map shows a Native-built causeway to Rocky Neck, for example. According to one colonial account, Cow Island in the Annisquam, now part of the mainland, is another example.38 Earthworks and stoneworks are a well-documented feature of Native American culture in New England.39 The Pawtucket also strategically reduced and fortified natural causeways to create easily defended islands. Necks of land, such as Marblehead Neck, and peninsulas with narrow access were desirable as redoubts against enemy attacks. Nanepashemet’s summer retreat at Marblehead Neck is an example.40 Colonists later used the river islands in husbandry to segregate (or impound) animals by species or sex—hence the names Cow Island (or Milk Island), Ram Island, Hog Island, Pound Island, and the like.

Cow Island with Causeway, opposite Rust Island

Marblehead Neck

Marblehead Neck

Although the people were connected with each other in multiple ways, they did not constitute a monolithic culture, act unilaterally, or move en masse. Every family followed its own preferences and stayed or left campsites and villages at will. Before they became villagers, the Pawtucket were exclusively seasonal migrants. Each spring for about a thousand years, families left their permanent winter settlements, such as Wamesit in Lowell, and dispersed to their summer camps in Agawam and Wenesquawam to fish and later to farm .41 The Lowell-Lawrence area, the Pawtucket home base at the junctions of the Merrimack, Concord, and Shawsheen rivers, has surprising proximity to Gloucester—a day’s walk. It was an easy trek of less than 30 miles by land and canoe, with portages from the Shawsheen Valley to the Parker and Ipswich rivers.42

Shawsheen Watershed

Shawsheen Watershed

Shawsheen River

Shawsheen River

This seasonal migration between fixed points within the same small area is not the same as nomadism. Nomads are pastoralists who continually wander within a much larger territory to find fodder for the domesticated herd animals on which they depend. Native Americans of New England did not have domesticated animals, and they were not wanderers. At the same time, their villages were not strictly permanent with complete sedentism leading to city-building. The people did not build permanent structures but moved their villages within an area to take advantage of fresh soils and water supplies and seasonal subsistence and luxury resources. This mixed economy with a lack of cities and monumental architecture led early historians and anthropologists to dismiss Algonquian societies as comparatively lacking in “civilization” or “culture”. Even early archaeologists regarded New England Indians as inconsequential, especially compared to the civilization builders of Mexico and Central and South America. Algonquian sites were shell heaps and burial mounds rather than temples and pyramids.43

So this was Agawam and Wenesquawam. The Pawtucket and their Algonquian ancestors and the people who preceded them came here by these coastlines, rivers, and trails over the past 11,500 years or more. The ground we live on today conceals traces of the lives of the 20 million or so other families who were here during that time hunting, foraging, fishing, digging for clams, and farming—including the Pawtucket family that according to Samuel de Champlain had a wigwam on my street in Cripple Cove on Gloucester Harbor. Now, what else did Champlain’s maps and journals tell us about Indigenous Peoples here?

Next: What did Champlain see in the “Cape of Islands”?

Notes and References

- Primary source accounts of Agawam include papers in the Essex Institute Historical Collections by Robert Rantoul (19: B126), Herbert Adams (19:153), George Phippen (1: 97, 145, 185), and Joseph Felt (4: 225), in addition to Felt’s history of Ipswich, which is based on colonial accounts. See, for example, Felt’s paper, “Indian Inhabitants of Agawam”, read at a meeting of the Essex Institute in Hamilton, August 21, 1862.

- Naumkeag and other villages, such as Mathabequa on the Forest River in Salem, are attested in the accounts of Edward Winslow in 1621 and 1624; members of Roger Conant’s party traveling from Fishermen’s Field in Gloucester to Salem Village in 1626; Francis Higginson’s account of 1629; and the 1680 testimonies of William Dixy, Humphrey Woodbury, and Richard Brackenbury, who described native farming settlements on the rivers running into Beverly and Salem harbors. See also Edward Stone’s History of Beverly, Civil and Ecclesiastical, from its Settlement in 1630 to 1842) and George Dow’s Two centuries of travel in Essex County, Massachusetts, a collection of narratives and observations made by travelers, 1605-1799 (The Topsfield Historical Society, Perkins Press. 1921).

- An account of Quasquacunquen (Quascacunquen) on the Parker River comes from Currier’s 1902 History of Newbury, which cites the Massachusetts Colony Records (Vol. 1: 146), Winthrop’s History of New England, p. 30, and Wood’s 1634 map of New England. These sources give Wessacucon or Wessacumcon as the original Indian name. In both forms, however, the name was a corruption of the native name for the Parker River and their village upon it. In addition, the name does not mean anything relating to the falls in Newbury in the Byfield parish, as claimed in all contemporary sources. The root words for water, falls, or river are not present in any form. Instead, in present-day Western Abenaki, as explained in Chapter 1, the name translates as “just right for gardens” (or “correct planting ground” or “perfect cropland”). Kwask (quasq; wess) = state of being + wai (ua; a) = “just right, correct” + kikwen (cunquen; cucon) = “fields for planting gardens/corn”, “cropland” = Kwaskwaikikwen (Quascacunquen; Wessacucon).

- The 1640 map of Newbury is from John J. Currier’s History of Newbury, Mass. 1635-1902: 63.

- When I asked to see their files on Native Americans, the Gloucester Archives in City Hall reported that there was only a folder of newspaper clippings and articles (the Peterson File), and that there were no Indians on Cape Ann at the time of English settlement!

- Massachusetts Historical Commission, 220 Morrissey Blvd., Boston 02125: https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/. My understanding of the workings and policies of the Massachusetts Historical Commission comes in part from a personal interview with Jonathan Patton, Preservation Specialist there, on September 5, 2013.

- LeBaron, J. Francis. 1874 (1931). Archaeological Atlas of Castle Neck, Ipswich. Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum. I am indebted to Tom Beddall of Ipswich for access to this map.

- Information about the specific geographic locations of Masconomet’s fort and residence and deeded land comes from Tom Beddall of Brookline and Choate Island, MA. His sources include 17th century documents in the Essex Quarterly Court Records, on microfilm in the Massachusetts state archives, transcribed in the 1930s by WPA workers under the direction of Harriet Silvester Tapley, author of Chronicles of Danvers (Old Salem Village) 1623-1923. Other sources brought to my attention by Tom Beddall are unpublished first-person accounts and anonymously published articles by Rufus Choate, referenced in Downriver: A Memoir of Choate Island by Mary Wonson, Roger Choate Wonson, and Agnes Choate Wonson. Rufus Choate, who signed his columns as “Chebacco” or “Observer” and the like, published, for example, an article on “Masconomet and His Foes—Where the Chief Lived” in the September 8, 1893 issue of Echo. A history of English occupation of Hog Island is set forth in Duane Hamilton Hurd’s History of Essex County, Volume 2.

- The history of Masconomet and his relationship with John Winthrop Jr. and the settlers of Agawam is recorded in John Winthrop’s Journal (1790); letters of John Winthrop Jr. in the Winthrop Papers; essays by Robert S. Rantoul in the Historical Collections of the Essex Institute in Salem (19: B126 and 4: 225), and in Joseph Felt’s History of Ipswich… (1966), available at archives.org. See also Felt’s paper “Indian Inhabitants of Agawam,” read at a meeting of Essex Institute on August 21, 1862, reproduced in the Essex Institute Historical Collections 4: 225-228.

- Goff, John V. 2008. Remembering the Tarratines and Nanepashemet: Exploring 1605-1635 Tarratine War Sites in Eastern Massachusetts. In The New England Antiquities Research Association Journal 39 (2): http://www.neara.org/images/pdf/tarratinewars.pdf. Also: Vaughan, Alden T. 1995. New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians, 1620-1675, 3rd ed., p. 52. The Tarrantine Wars are taken up in more detail in a later chapter.

- Descriptions of Algonquian defenses come from Edward Winslow’s narratives of 1622 (Mourt’s Relation) and 1624 (Good Newes from New England). Native forts in Salem-Beverly are also referred to in George D. Phippen’s testimony, “Of Salem before 1628” in the Essex Institute Collection, Volume 1 and Joseph Felt’s “Historical sketch of forts on Salem Neck”, Volume 5: 255. Old Castle on Castle Lane in Pigeon Cove, Rockport, is believed to have been built in 1712 by Jethro Wheeler and by virtue of its name was very likely built on the site of a native fort. In considering geography and the history of Tarrantine attacks, it seems certain that watchtowers would have been erected at points with clear sightlines to river entrances.

- For colonial laws and ordinances regarding livestock, see the Book of the General Laws of the Inhabitants of the Jurisdiction of New-Plimoth, and Generall Laws of the Massachusetts Colony, revised and published, by the Order of the General Court (1632-1676) http://www.princelaws.pdf; also at http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/tlc0200.jpg. See also the classic Nathaniel Shurtleff’ 1853 Records of the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay And General Court, Vol. I, 1628-1641 and Vol. II 1642-1649 in the Massachusetts Archives in Boston. A less convenient but to the point source on microfilm in the Archives is Volume 30: Indian, 1603-1705: Records detailing the interactions between the Massachusetts Bay government and native peoples in New England and New York, which is indexed.

- Deeds to Gloucester and other towns in Essex County—originals, typescripts, and historical context—are on the web site of the Salem Registry of Deeds, Native American Deeds Collection: www.salemdeeds.com/nativeamericandeeds/indiandeedsummary_9-20-06.pdf.

- The deeds Masconomet and his heirs signed are in the Salem (MA) Registry of Deeds. See also Peter Leavenworth’s article (1999), “The Best Title That Indians Can Claime”: National Agency and Consent in the Transferal of Penacook-Pawtucket Land in the 17th Century, New England Quarterly 72 (2): 275-300.

- See Sidney Perley’s 1912 The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts and Map of Indian Lands and Localities in Essex County Massachusetts. These documents are on the Salem Registry of Deeds web site. The text can be read on archive.org.

- Sidney Perley 1912: 88-134. See also Williams & Tyng et al., Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Volume 51 (1852).

- The story of Endicott’s surveyors talking to Indians at Wingaersheek is cited in Babson (1860); Adams (1882), The Fisher Plantation of Cape Anne, Part I of The Village Communities of Cape Ann and Salem, Historical Collections of the Essex Institute: 19; and Thornton (1854), The Landing at Cape Ann: or, The charter of the first permanent colony on the territory of the Massachusetts Company. My refutation of the idea that Wingaersheek is a “low Dutch German loan word and etymology for Wingawecheek are laid out in Chapter 1.

- Gloucester Daily Times, November 13, 1940. Cape Ann Rich in Indian Relics Rotarians Told

- Carleton Phillips, 23 samples of pottery from Riverview; Phillips, N. Carleton. 1940 and c. 1941. Unpublished untitled transcripts of talks given in Gloucester (MA) on the archaeology of Cape Ann. Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Museum. See Mary Ellen Lepionka, Fall 2013, Unpublished papers on Cape Ann Prehistory. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (2): 45-92. Also: Lepionka, Fall 2017, Speck in Riverview. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (2): 60-70. See also Frank Speck, Massachusetts Indians, especially relating to Cape Ann, Gloucester Daily Times, Aug. 4., 1923; and Dodge, Ernest S., 1991, Speck on the North Shore, in the Life and Times of Frank G. Speck (Roy Blankenship, ed.): 42-50.

- Reference to Endicott’s 1642 division of the Indians’ “hoed land” on Cape Ann is in The charters and general laws of the colony and province of Massachusetts (Boston, MA: B.T. Wait and Co., 1814). See also Young, Alexander. 1846, Chronicles of the First Planters of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1623-1636, Volumes 41 and 49. Boston, MA: C. C. Little and J. Brown, and Phillips, James Duncan. 1933. The Landing of Endecott. Chapter IV in Salem in the Seventeenth Century. Boston: Houghton.

- Documentary evidence includes letters of the first settlers, anecdotal accounts of visitors and descendants, records of Indian land sales, and a hand-drawn map locating an Indian plantation at Old Garden Beach. Cornhill St. for Middle St. appears on an early map and is noted in Babson (1860).

- “Names of the Rivers and the names of ye cheife Sagamores yt inhabit upon Them from the River of Quibequissue to the River of Wenesquawam.” [“from the Penobscot to the Annisquam”], n.d. (c. 1602-1610); British Library, Egerton Manuscripts 2395 [Fol. 412]. Wonasquam appears on Capt. John Smith’s 1614 Map of New England [in 1605]: http://www.plimoth.org/education/teachers/smithMap.pdf. The detail of Wonasquam on Wood’s map comes from Robert Raymond, 1926 (Reprinted 1969), William Wood’s Map and Description of New England in 1635 (from New Englands Prospect…,William Wood, 1635, pp. 31-38). Also appears in A Book of Old Maps Delineating American History…, Emerson D. Fite and Archibald Freeman, eds.: 136-139: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~raymondfamily/WoodMap.html. Josselyn’s reference to Wonasquam appears in his 1674 (reprinted 1865) An Account of Two Voyages to New-England Made during the years 1638, 1663: http://archive.org/details/accountoftwovoya00joss.

- Dunton, John. 1686. Letters Written from New England. Prince Society Publications Issue 4, Ayer Publishing (1966 edition).

- Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1846), John Dunton’s Journal: 121-122.

- Roger Williams’ account of Agawam and Narragansett burial practices is Chapter 32 of his book A Key into the Language of America (1643).

- For information on Passaconaway and his descendants, see Russell Lawson’s Passaconaway’s Realm (2002) and Charles Beals’ Passaconaway in the White Mountains (1916). For Nanepashemet and his descendants, see Ellen Knight’s Nanepashemet Family Tree in the Wiser Newsletter. Volume 11, Issue 2 (2006): Nanepashemet.pdf.

- I used Frederick William Gookin’s 1912 biography Daniel Gookin 1612-1687, Assistant and Major General of the Massachusetts Bay Colony: His Life and Letters and Some Account of his Ancestry. The discrepancy in the date of his death is because until 1752 the colonial year began on March 25. Thus Gookin’s March 19 death date would have been in 1686, the same year that Wonalancet and Owufsumug died and John Dunton visited Wonasquam. Moderns have corrected pre-1752 colonial dates to correspond to a January 1 start date for each new year, although for dates between January 1 and March 25 some scholars write the alternatives with a slash, e.g., 1986/87.

- See Ebenezer Pool, Pool Papers, Vol. I (1823). This is a typescript ms, in the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester. A handwritten original (or copy) is in a filing cabinet in the basement of the Sandy Bay Historical Society.

- Pool’s reference to installment payments and payments in kind rather than cash are born out in Harry Wright’s 1941 article, The Technique of Seventeenth Century Indian Land Purchases, in Essex Institute Historical Collections 77: 185-197. The Massachusetts Historical Commission Archives in Boston has Records of Deeds by the Massachusetts General Court between 1620 and 1651; Gloucester Records for 1642-1874 (Microfilm A 632); Town Records of Deeds for Gloucester and others from 1701 to 1914; the Commoner’s Book for 1707 to 1820; and Minutes of Meetings of Proprietors of Common Lands. Gloucester Town Records (Vol. I 1642-1714) in the Gloucester Archives in City Hall do not refer to purchases of Indian lands. Gloucester’s 1684 purchase of Pawtucket land on Cape Ann is in the Book of Indian Records for Their Lands in the DuBois Library at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. The Massachusetts Historical Commission in Boston also has a copy.

- Lepionka, Mary Ellen and Mark Carlotto. Spring 2015. Evidence of a Native American Solar Observatory on Sunset Hill in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 76 (1): 27-42.

- For an appreciation of the importance of skywatching in the ancient world, see John Mitchell’s 1984 Ceremonial Time: Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile. See also Anthony Aveni’s People and the Sky (2008), and Lynn Ceci, 1978, Watchers of the Pleiades: Ethnoastronomy Among Native Cultivators in Northeastern North America. Ethnohistory 25 (4): 301-317.

- See Obadiah Bruen’s Town Record of 1650 and the Babson about the naming of hills in the development of Gloaster Plantation (Gloucester).

- David Stewart-Smith’s and Frank Speck’s ethnographies and the works of Colin Calloway were my principal anthropology sources for understanding Pawtucket-Pennacook social organization, political structure, and kinship system.

- The story of Samoset, an Abenaki sagamore, who greeted the Mayflower colonists in English and introduced them to Squanto (Tisquantum), a returned Patuxet kidnapee, comes from William Bradford’s history of Plimoth Colony, Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s Relation, Christopher Levett’s Voyage to New England begun in 1623 and ended in 1624, and the 1893 biography of Levett (sometimes written as Leverett; Bradford wrote Levite) by James Phinney Baxter.

- The trail maps were created in 2002 by GIS Director Tom O’Leary of the Southern Essex Registry of Deeds (used with permission). They are in the Native American Collection on the web site of the Registry of Deeds as Ancient Indian Trails and Canoe Routes of Essex County. More trail maps for the Pawtucket-Pennacook may be found in Chester Price’s 1958 article, Historic Indian Trails of New Hampshire (The New Hampshire Archaeologist 14: 1-33), and in Wilkie and Tager’s Map of Native Settlements and Trails c. 1600-1650, page 12 in the Historical Atlas of Massachusetts (1991). See http://www.geo.umass.edu/faculty/wilkie/Wilkie/maps.html.

- Phillips, Stephen Willard. October 1955. Evolution of Cape Ann Roads and Transportation 1623-1955. In Transportation. Salem, MA: Essex Institute Publications.

- Haviland, William A. 2012. Canoe Indians of Down East Maine. Charleston, SC: The History Press. Also, Edwin Tappan Adney, 1964, Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America (with Howard I. Chappelle). Bulletin of the United States National Museum (Washington DC), Republished in 2014 with Howard Chapelle and John McPhee, Skyhorse Publishing (New York).

- Information about native canals and causeways is anecdotal or ethnohistorical, based on colonists’ accounts, cited in the early histories of Newbury and Ipswich. See, for example Joshua Coffin’s 1845 A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, from 1635 to 1845, John Currier’s History of Newbury, Mass. 1635-1902, and Joseph Felt’s History of Ipswich.

- The Cow Island causeway at the southern end of Riverview, which no longer exists, is referenced in Stephen Phillips’ article, Evolution of Cape Ann Roads and Transportation 1623-1955, in Transportation (October, 1955, Essex Institute Publications). Cow Island is now indistinguishable from the Riverview mainland. The map is a detail from Plan of Annisquam River in City of Gloucester, made in December 1911. It is online as a product of a defunct government agency, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Harbor and Land Commissioner’s Office, which operated in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

- Native rock features and stoneworks, including ceremonial stone landscapes (CSLs) and petroglyphs, are taken up in greater detail in Chapter 7.

- Roads, Samuel. 1880. History and Traditions of Marblehead, Chapter I. Boston: Houghton Osgood & Company.

- Pawtucket seasonal migration between Wamesit in the vicinity of Lowell and the Essex County coasts is attested in the accounts of John Winthrop Jr., Daniel Gookin, Joseph Felt, and the earliest histories of Lowell, Chelmsford, Billerica, and Dracut, including Charles Cowley’s 1862 Memories of the Indians…. (Vol. I). Also Frederick Coburn, 1920, History of Lowell and Its People.

- Depending on water level you could travel by canoe from Ipswich Bay to the Merrimack River with only minor portages via the waterways of the Shawsheen Valley. Each of these locations had desirable resources. For example, outcrops on the Skug River were the nearest sources of steatite or soapstone for carving bowls and atlatl weights. Following the Shawsheen River you would come out in the vicinity of North Andover or Lawrence and then would travel west on the Merrimack to Pawtucket Falls and Wamesit in Lowell. See https://www.fonat.org/shawsheen/.

- The prejudicial view that New England Algonquians were inconsequential because they “wandered” and did not build cities or monuments was first expressed by early archaeologists of the post-Civil War era, such as F. W. Putnam, and has tended to persist until the present day.

Great to read about the local indigenous history, but I’d appreciate if you could edit to add your references at the bottom. I’d love to be able to follow up and read the documents that you cite. Thank you!

extraordinary account. I wish I could have better/clearer view of the maps posted. They come up a bit grainy in my MacBook…It’s hard to believe there is no provision to teach local history to schoolchildren. It seems we should know more about these original Native American lands. I LIVE on Agawam Ave in Haverhill and did not know that the area of Bradford and this avenue were originally AGAWAM people.