Shell Heaps and Graves

Early archaeologists and historians of the nineteenth-century after the Civil War for the most part discounted Indigenous history in Essex County. As D. F. Lamson wrote in his history of Manchester, Massachusetts, “Their shell heaps and their graves are the only remains left to show that they once called these lands their own.” [1] Over the next hundred years amateur and professional sleuths mapped, described, and dug up all the shell heaps and graves they could find. Discoveries and exhumations of Indian graves were reported in local newspapers as great curiosities or ghost stories. Skeletal material, especially skulls, were sent to Harvard for forensic analysis, which in those days reflected ideas about phrenology and eugenics. Grave goods in good shape found their way into museum collections, with the rest typically discarded as detritus. Modern streets, cellars, foundations, power lines, and cemeteries for town fathers replaced Indigenous burial grounds. Today, the oldest cemeteries, such as Seaside Cemetery in Lanesville, undoubtedly contain Indigenous burials that were missed. Some settler cemeteries have sections that were set aside for Native American and African slaves.

From the Middle Archaic Period on, Indigenous Peoples harvested shellfish and preserved the meats through drying to store or trade. The New England coast was covered with piles of shell refuse. According to folk history, a shell midden at Wheeler’s Point had reached 10 or 12 feet in height before being mined for lime and fill beginning in the 1800s. Artifacts at midden sites include stone lap anvils, small hammerstones, and curved stone knives that the harvesters used to open the shells. On Cape Ann, extensive shell middens existed on the Annisquam River islands, such as Pearce Island; in Riverview’s coves, such as Curtis Cove; in Annisquam’s coves, such as Lobster Cove and Goose Cove; on the shores of Essex Bay, such as Conomo Point and Clamhouse Landing on the Essex River; and in the dunes of the sandy beaches all along Ipswich Bay, including Plum Island, Little Neck, Castle Neck, Coffins Beach, and Wingaersheek.

Shell middens were mined for making lime and fill. In 1950 the massive Wheeler’s Point shell midden, making up most of the land at the end of the peninsula in Riverview between the Annisquam and Mill rivers, was used as fill for the footings of the Andrew Piatt bridge linking island Gloucester to its West Gloucester mainland. A residential neighborhood sits on the remains of that shell heap today. A few accounts report large settlements with 20 or more wigwams in Riverview at some times that seemed to disappear at other times. One early observer noted, “Towns, they have none”[2] and the stereotypical perception of Indians as “nomads” became established. Later professional archaeologists (and some Indigenous historians) have debated the existence of permanent agricultural settlements in southern New England, based on tradition, or debating as evidence the number of preserved corn kernels recovered from a site!

Archaeological evidence for camp and village sites on Cape Ann nevertheless comes mainly from surveys and excavations conducted in the first half of the 20th century. Researchers included Marshall Saville, Rockport-born Harvard archaeologist, one-time director of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York, and founder of the Sandy Bay Historical Society where his collection is stored; N. Carlton Phillips, president of the Russia Cement Company (LePage’s Glue) in Gloucester and an avid amateur archaeologist (his collection is stored in the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester and the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough); Frank Speck, a University of Pennsylvania ethnologist who specialized in Eastern Woodland Indian cultures and summered in Riverview; and Speck’s student Frederick Johnson, one-time director of the American Anthropological Association and the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology in Andover (some of their finds were sent to the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, in New York–today the Smithsonian). Their reports and collections, along with the countless casual finds of artifact collectors and residents, all point to well-populated pre-Contact native settlements on Cape Ann over the past 7,500 years or more.

Settlement Patterns

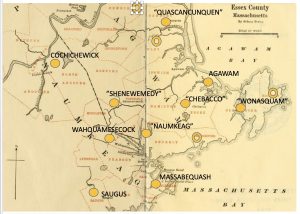

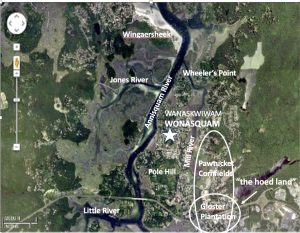

So where were the Pawtucket villages? Although there is little physical evidence to go by, and it is often contested, there really can be little doubt that before 1600 the Pawtucket had year-round agricultural villages along the coastal plain of Essex County. We can know by inference from documentary and cartographic evidence and by the practical needs of performing maize agriculture, which requires on-site attention for 7 or 8 months of the year. The first English coastal settlements in Gloucester, Ipswich, Newbury, Beverly, Danvers, and Salem were explicitly chosen because of the availability of open areas already cleared and prepared for cultivation by Indigenous farmers in nearby villages. As John Endicott reported to John Winthrop in 1638, I have bought “the hoed land” from the Indians on Cape Ann, which became the site of Gloster Plantation. As noted in records of the Plymouth Company, New England Company, Massachusetts Bay Company, and in the papers of their first governors, the first English settlements in Essex County were explicitly chosen for their proximity to land already cleared and cultivated by the Pawtucket (Leavenworth 1999; McBride 2003; Perley 1912; Wright 1941). Those lands included, for example, Gloucester (Wenesquawam/ Wonasquam/ Wanaskwiwam), Ipswich (Agoaum/Agoamin/Agawam, where Masconomet gifted his farm on Argilla Road to John Winthrop Jr.), Newbury (Quascacuquen/Kwaskwaikikwen), Topsfield (Shenewemedy/Shinnewenameti), Andover (Cochichewick/Cochichewicket), and Beverly (Naumkeag/ Nahumkeak).[3]

This kind of evidence contradicts the older dogma claiming that until European contact the Algonquians were only seasonal migrants lacking permanent settlements. As one archivist explained to me (in disparaging tones, repeating an ancient refrain), “Some of them may have filtered down through the woods to fish here, but they never lived here.” An Abenaki scholar also told me that Algonquians did not have permanent villages. I pointed out that her ancestors may not have had permanent villages, because they were hunter-gatherers living in northern New England and were not farmers, and that agriculture requires many months of attention in situ. Although hunting, trapping, gathering, visiting, trading, quarrying, and warring parties dispersed at various times of the year for various purposes, the principal agricultural villages—the precise locations of which shifted slightly every few years on the basis of soil fertility—always had some people living in them at any given time, as witnessed by the earliest settlers. According to Josselyn, for example:[4]

They live for the most part by the Sea-side, especially in the spring and summer quarters, in winter they are gone up into the Countrie to hunt Deer and Beaver and the younger ones going with them.

It is also not true that the coast would have been inhospitable in winters, forcing people to move inland. If anything, the opposite is true. Aside from the occasional Nor’easter, the coastal climate is actually ameliorated by proximity to the ocean, making summers cooler and wetter, and winters warmer and dryer than in the interior. If the Maritime Archaic people could live year-round among the rocks on the shore for 10,000 years, for which there is ample evidence, there is no reason the Algonquians could not have done so as well, especially with so many sustainable subsistence resources concentrated in closely proximate estuarine, wetland, and forest ecosystems.

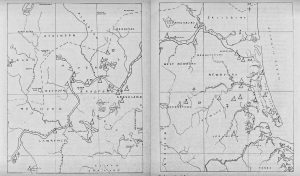

Kinds of settlements other than agricultural villages were seasonal camps at resource procurement sites. The Pawtucket village of Wamesit (Lowell MA) at the intersection of the Merrimack River and the Concord River was both a permanent village and a winter gathering place for bands on hunting and trapping expeditions. Pawtucket Falls (near Lawrence MA) and Amoskeag Falls (Manchester NH) were favorite spring gathering places for great numbers of bands on fishing expeditions for anadromous fish. In his 1830 archaeological survey of the Merrimack watershed, Warren K. Moorehead mapped the locations of Indigenous settlements along the rivers as well as their seasonal fishing and shellfishing camps on Plum Island Sound.[5]. Moving between villages and seasonal camp sites within the same geographic area is not nomadism.

Detail from Moorehead’s maps[6]

Another canard is the claim that indigenous people established villages only in the late seventeenth century by following European models or by squatting around European trading posts.[7] People living on the Gulf of Maine were interacting with Basque, Breton, French, English, and Dutch fishermen, whalers, explorers, and fur traders for a hundred years prior to European settlement or attempts at colonization. Those early contact agents reported that in southern New England Indigenous farmers were already living in villages. They were descendants of agriculturalists in the Mississippi, Ohio, and Susquehanna valleys, and there is no reason they would not also have had agricultural villages wherever environmental conditions permitted. Arguments denying Native agency in civilization building are holdovers from an earlier epoch when archaeologists spurned low artifact-density New England shell heaps and simple graves in favor of the monumental architectures and extravagant cultures of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca kingdoms of Central and South America.

The pre-Contact rise of year-round farming settlements in Essex County may have occurred through the following sequence of developments:

- During seasonal migration, people set fishing nets and weirs and planted corn.

- Corn and seafood surpluses were preserved, cached, and traded.

- Surpluses led to increases in population size, stability, and density.

- People increased production using mobile farming to meet demand.

- Year-round settlements were established based on proximity to planting grounds.

- Proximity to year-round availability of seafood and forestry products reduced the risk of food production and enabled a mainly sedentary settlement with a secure mixed economy.[8]

So village sites are hard to locate here, but not because there were none. There is ample archaeological, documentary, cartographic, linguistic, environmental, and locational evidence for them. Environmental factors making coastal villages difficult to locate include river embayments, sea level rise, and cycles of flood plain erosion and redeposition. However, sites are difficult to locate mainly because of commercial and residential development, which has obliterated them. Village sites, sites of Native fortifications, and cultivated lands were the first to be leased, bought, or appropriated. Colonists built on top of them, and sites have also been destroyed through later urban development.

Environmental Factors in Indigenous Settlement Patterns

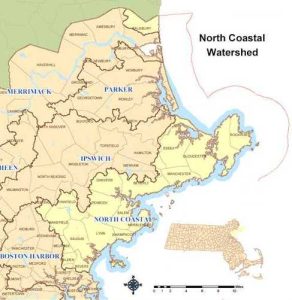

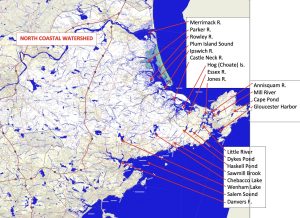

Estuaries, watersheds, river systems, and drainage patterns are fundamental to understanding the history of habitation here. Essex county watersheds include the Charles River basin on the south and the Merrimack River, Salmon Falls-Piscataqua River basins on the north, and the north coastal watershed of the rivers that empty into Ipswich Bay and Massachusetts Bay, such as the Parker, Rowley, Essex, Ipswich, Annisquam, and Danvers Rivers. Pawtucket occupied these watershed areas and along the Merrimack’s many tributaries in New Hampshire as well and in northern Essex, Middlesex, and Worcester counties.[9]

River Drainage Systems of New England and and an Overview of the Parker, Ipswich, and North Coastal Watersheds

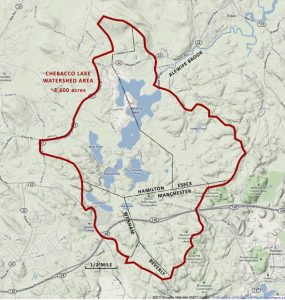

The Chebacco (Essex) Watershed and the Annisquam Watershed

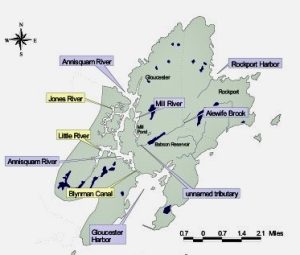

Some Essex County Waterways

According to ethnographers, land at each junction of a river with its tributary would have been occupied and used by an extended family according to hereditary right or custom or according to assignment by a local sagamore.[10] The number of people a site and its resources could support affected the size of a band and the frequency with which a group had to split off to occupy a different area or start a new band. Life depended on the rivers and their bounty, the arable upland in the intervales between the tributaries, and the interactions of the rivers with the sea. Prior to and during the Contact Period, these same river junctions that supported hundreds of generations of seasonal migrants gradually, and sometimes suddenly, became the sites of Indigenous agricultural villages.

Estuaries—where the outflows of rivers and streams mix with salt water in ocean tides—are the spawning grounds or nurseries for many species of fish and shellfish. It may be less well known that estuaries also are optimal bioregions supporting the development of agriculture, because the abundant resources of that environment reduce the many risks of engaging in food production.[11] The supply and diversity of year-round food resources in an estuary can ensure people’s survival in case of crop failure. At the same time, because of the diversity and abundance of food at hand, people living on the estuaries did not specialize in food production.[12] More than inland people, such as the Iroquoians, who came to depend on maize for their living, the coastal Algonquians retained a mixed economy.[13] They made their living by hunting, gathering, fishing, clam digging, trapping, fowling, gardening, and farming.

An estuary bioregion: Ipswich and Rowley rivers and Plum Island Sound [14]

Benefits of Estuary Bioregions in Essex County

- Year-round readily accessible supply of food.

- Deep-sea & anadromous fish (mackerel, bass, sturgeon, salmon, haddock, herring, swordfish); shellfish (quahogs, oysters, clams, mussels); and eels.

- Land & sea fowl (turkey, ducks, geese); marine mammals (harbor seal, porpoise, whale); small and large game (hare, otter, beaver, deer, bear, raccoon, fisher, porcupine, squirrel, etc.).

- Salt marsh, fresh marsh, and abundant fresh water.

- Forests and meadows for wood, bark, fibers, firewood, acorns, groundnuts, chestnuts, black walnuts, beechnuts, sassafras, herbs, plums, strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, blackberries, gooseberries, and mushrooms.

- Tidal rivers, bays, and beaches for marsh grasses, cattails, sumac, wild rice, clay deposits, shellfish beds, shells, canoe access, and trade routes.

- Fertile riverine soils and intervales in the uplands for cultivation of corn, squashes, melons, beans, tobacco, Jerusalem artichokes, sunflowers, and other plants.

- Abundant stone outcrops, rocks, minerals, and gemstones for shelter, stone tool manufacture, defense, astronomical observation, spiritual use, and trade goods.

These environmental features relate to the Office of the Massachusetts State Archeologist’s list of criteria for the siting of Native villages in coastal Massachusetts:[15]

Locational Criteria for Village Siting

- On a partly submerged terrace on an outflow plain.

- At the junction of 2 or more tidal rivers.

- Less than an 8-degree slope.

- Within 1,000 ft. of permanent fresh water.

- Near southwest-facing land with stratified, undisturbed, fertile soil.

- Near abundant sources of fuel.

- Near north-facing soft earth overlooking water, for burial grounds.

- Near rock outcrops for wind and sea protection and defensive positions.

Other locational criteria include proximity to terraces with sandy or gravelly soil for caching food and goods; proximity to river channels for fishing and canoe transportation; proximity to swamps (refuge areas in which nearly every living thing is useful as food, medicine, or fiber); and proximity to rocky heights used as ceremonial gathering places and astronomical observatories.

The Role of Mobile Farming

Pawtucket farms and farming villages on Cape Ann were not permanent in the way that African and Eurasian Neolithic villages were, which led to the building of monumental architectures and the world’s first cities. Without irrigation, aquifers, or extensive fertilization, and with corn rapidly depleting the soil of nitrogen, Algonquian cornfields had to be periodically relocated within an area to find fertile soil. In coastal areas arable soils tend to be in comparatively small areas and discontinuous pockets. The small scale of farming and the mobility of farmers contribute to the difficulty of locating village sites.[16] The coastal Pawtucket cleared gentle hillsides through swiddening, planted corn through bunding in raised beds, and made or reoccupied whatever wigwams were nearer to wherever their corn crop was planted in a given year. Villages thus were mobile within a circumscribed area, but really no less permanent, as the area retained its place name and the people retained their affiliation with it, just as “Boston” remains “Boston” regardless of which neighborhood you or other residents are occupying at a given time.

Unlike subsistence economies relying only on hunting and gathering, economies based on agriculture can sustain larger populations continuously within the same geographic area. Agriculture-based economies also support crop specialization, mass production, and trade. Agrarian life thus favors permanent settlement. In addition, the European fur trade, which may have involved coastal Algonquians as early as the fourteenth century, favored more permanent settlements on the coast for proximity to trading posts established prior to European efforts to colonize. Known European contact through trade predated English settlement of Cape Ann, for example, by more than a hundred years. Early French explorers reported that coastal Abenaki of Maine and New Hampshire were already familiar with European fishing fleets and trade goods, had European-style clothing and accessories, and even spoke a Basque-Abenaki patois as a language of trade.

Geospatial Analysis

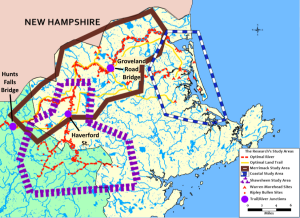

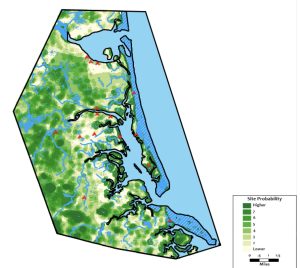

In my quest to locate Pawtucket villages in Essex County, I found that existing on-the-ground locational criteria were not strictly applicable to this area. Also, there were clues from documentary and ethnohistorical evidence that needed to be mended with the environmental data. I worked with a graduate student who applied geospatial analysis and GIS mapping to a corpus of village data–actual sites identified in professional archaeological surveys in three study areas: the Merrimack, Shawsheen, and Parker River valleys, testing the relative predictive value of various environmental factors. A few other recent studies have employed geospatial analysis and GIS mapping to archaeological problems such as finding village sites.[17] The study showed that in the interior, village sites were located on flat land above the flood plains of major rivers, for example, but on the coast the greatest predictors of village location are proximate hills and wetlands. Maps of the study areas were rendered in which the darkest colors indicate the highest probability of finding a village site.

Coastal study area map with probabilities of finding village sites[18]

Coastal villages most often were at the foot of small hills (with the southwest-facing hillside cleared and planted in corn), between a spring-fed swamp and a river or tidal waterway. In Gloucester the most likely places to find evidence of pre-Contact field cultivation would be on Mill River above Mill Pond, for example, and under the Middle School parking lots and playing fields, Veteran’s Way, the Public Works Department and Poplar Street, and in Riverdale along Washington Street and Cherry Street.[19] Also more predictive on the coast than inland are expanses of fire-resistant and heat-enabled trees, such as pines, oaks, hickories, and beeches.

The Role of Transportation and Trade

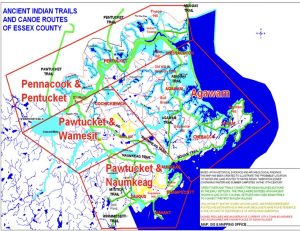

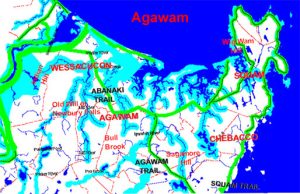

The geospatial analysis study also showed that large permanent settlement sites can especially be found at the junctions of major trails with major canoe routes on rivers, pointing to the importance of networks for transportation and trade. Trails also connected the main Indigenous villages. In Essex County the Squam Trail (Rtes. 127 and 133), for example, connected Wonasquam to Naumkeag and Agawam; the Abenaki Trail (Rte. 1A) connected Agawam to Naumkeag and Quascacunquen (Kwaskwaikikwen) and the northeast coast, and the Naumkeag Trail (Rtes. 62, 97, and 114) connected Naumkeag to Topsfield (Shenewemedy) and Andover (Cochichewick) and the Merrimack River at Wamesit.

Registry of Deeds Trail Maps[20]

The Indigenous trails tested in the geospatial analysis study included present-day highway routes 1A, 22, 62, 97, 110, 113, and 133. Of these, the most spatially optimal trails were state routes 110, 133, and 97 and US Route 1A. The most spatially optimal rivers in the three study areas were Lubbers Brook, Martins Brook, Merrimack River, Mill River, Parker River, Shawsheen River, and Strong Water Brook. These waterways provide access between the Merrimack, the Parker, and the Ipswich rivers, and to the resources of Plum Island sound and Ipswich Bay. There were three junctions of optimal trails with optimal canoe routes with the highest probability of village site location, which proved to be 100 percent accurate.

Gondola Trail-River Junctions Map

The purple dots on this map at the intersections of optimum trails with optimum canoe routes coincide with the three largest Pawtucket villages in the areas under study at the time of European contact. These were, from east to west, the villages of Pentucket (Haverhill), Shawshin (in the Shawsheen Village Historic District in Andover), and Wamesit (Lowell).

Settlements on Cape Ann and Vicinity

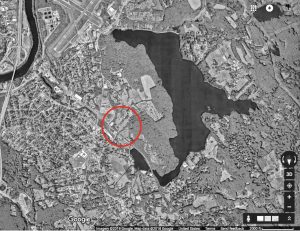

Pawtucket life in Gloucester clearly centered on the Annisquam River. The main village of Wonasquam (Wenesquawam/Wanaskwiwam) was on the Riverview peninsula, just north of Pole Hill, as described in the papers of John and Ebenezer Pool (1823), Daniel Gookin’s reports (1670s), John Dunton’s letter (1686), and other sources. Wonasquam, which had a depth of occupation dating from the Middle Archaic Period to the Contact Period, was excavated by the amateur archaeologist N. Carlton Phillips in the late 1930s. The village was centered around the heron pond off Wheeler Street. The pocket park known as Brown’s Field is a vestige of it that has remained undeveloped. Pole Hill was a spiritually significant place and served the villagers as an astronomical observatory.[21]

Wonasquam, Pole Hill, and Brown’s Field

Smaller satellite settlements were located on the Annisquam’s tributaries (Little River, Jones River, Mill River), and there were family compounds and camp sites on the islands, beaches, and coves all around the cape. During the Contact Period, Pawtucket were living where the Cape Ann Camp Ground is today, behind Wingaersheek Beach (the Matz site). The satellite settlement at Wingaersheek extended to Coffin’s Beach and the Jones River Saltmarsh. Others were on Little River in West Gloucester (called Agamenticus), for example at Presson’s Point and Kent’s Cove in West Parish, and on Lobster Cove in Annisquam. Settlement sites lie under Washington Street, Riverview Road, Concord Ave., Atlantic Street, Bray Street., Leonard Street, Sayward Street, Middle Street, and Centennial Ave., on Pearce Island and Rust Island, Thurston Point, Riggs Point and Langsford Street, and at Dykes Pond and Lily Pond, and under Stage Fort Park where Samuel de Champlain and later the Dorchester Company first met the Pawtucket living on Gloucester Harbor. In Rockport there were settlements or camps on Old Garden Road, Mill Brook, Penzance Road, Phillips Ave., Andrews Point, and South Street; in Essex on Southern Ave. and Chebacco Lake; and in Manchester-by-the-Sea on Old Essex Road and Old School Street at Sawmill Brook, with nearby Cedar Swamp and The Megaliths (formerly Agassiz Rock, a spiritually significant place).[22]

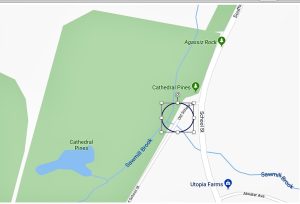

Pawtucket settlement in Manchester-by-the-Sea

An unnamed agricultural village with an estimated 40 inhabitants was located in Manchester MA at the junction of Sawmill Brook with Old School Street, adjacent to Cathedral Pines, Cedar Swamp, and the hill with The Megaliths (formerly called Agassiz Rock). Their planting grounds were just to south in an area the colonists called “The Plains”.

An unnamed agricultural village with an estimated 40 inhabitants was located in Manchester MA at the junction of Sawmill Brook with Old School Street, adjacent to Cathedral Pines, Cedar Swamp, and the hill with The Megaliths (formerly called Agassiz Rock). Their planting grounds were just to south in an area the colonists called “The Plains”.

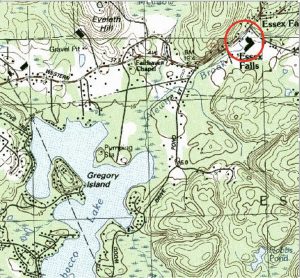

Pawtucket settlement Essex

Chebacco was the name of an area that extended beyond Essex from the Rowley River to the Annisquam River. There were a number of settlements in this area, including a settlement near the outflow of the Chebacco Lake, most likely on Alewife Brook at Essex Falls where it joins the Essex River. A Contact Period site at Essex Falls was excavated by Eugene Winter of the R. S. Peabody Museum in Andover. Families had camps all around the lake as well.

Chebacco was the name of an area that extended beyond Essex from the Rowley River to the Annisquam River. There were a number of settlements in this area, including a settlement near the outflow of the Chebacco Lake, most likely on Alewife Brook at Essex Falls where it joins the Essex River. A Contact Period site at Essex Falls was excavated by Eugene Winter of the R. S. Peabody Museum in Andover. Families had camps all around the lake as well.

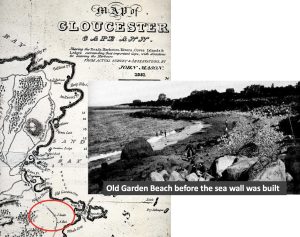

Pawtucket settlement in Rockport

An unnamed horticultural village was on a terrace above Old Garden Beach in Rockport. The name of the beach was inspired by the pre-existing Pawtucket planting grounds there. Satellite settlements extended from the Headlands to Whale Cove and Flat Point, along Mill Brook (aka Davison’s Run), and there was a significant Pawtucket presence in Pigeon Cove around Pool Hill.

Map of other main village sites

Some Other Village Sites in Essex County

“Agawam” was in the crook of Castle Neck and the Castle Neck River in Essex Bay in Ipswich (a site under a sand dune identified today as “Wigwam Hill”) (LeBaron 1874; Davis 1996).[23] There was a settlement in Essex at Essex Falls where the Essex River drains Chebacco Lake (Chebacco/Jebacho) (Choate 1890). Kwaskwaikikwen (Quascacunquen) was at Old Town on the Parker River in Newbury. An individual known to history as Great Tom had a farm at a site identified today as “Indian Hill” in West Newbury, near headwaters of the Artichoke River, a Merrimack River tributary, and “Old Will” Pumpasanoway had a homestead at Crane Pond Hill in West Newbury.

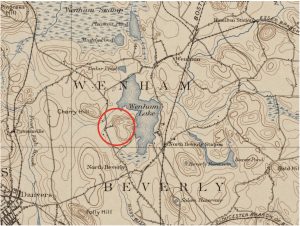

“Naumkeag” was on the Bass River in North Beverly near the outflow of Great Pond (Wenham Lake) (Hubbard 1680 [1815]). “Shenewemedy” was at the junction of Fish Brook with the Ipswich River in Topsfield (Webber and Nevins 1877), but may originally have been located farther east at the junction of another stream with the Ipswich River at the Topsfield Fairgrounds, which the colonists reportedly found planted with Indian corn. “Cochichewick” most likely was on the river of that name near the outflow of the lake by that name, on the southwest side of Weir Hill, just past Wolf Marsh (which the colonists drained) and Stevens Pond (created when the colonists dammed the river) (Abbott 1829). There was also Squompscut (Swampscott), Massabequash on the Forest River in Salem-Marblehead (Winslow 1624), Wahquamesecock between the Waters and Porter rivers in Danvers (Felt 1827 [1845]), and “Saugus” on the Saugus River at its outflow from Lake Quannapowitt in Wakefield, to name just a few.[24]

Village site of Agawam

The village of Agawam was centered at present-day Town Hill on the northern bank of the Ipswich River, with settlements in surrounding areas, for example, at Wigwam Hill on the Crane Estate, on the Castle Neck River, guarded by a fort, called Great Castle, on a spit of land off of Round Island, which is an extension of Choate Island in Essex Bay. People also lived on the eastern flank of Castle Hill, the southwestern slope of Hog (Choate) Island and other hillsides. The people’s gardens, cornfields, and burial grounds were along Argilla Road. Masconomet and his family lived for a time on Town Hill, which was originally called Sagamore Hill. He later moved to a hill in the part of Ipswich called “The Hamlet” (South Hamilton today), which became the new “Sagamore Hill” as the original Sagamore Hill’s name was changed to Town Hill. Families also had camps on Cross Island in Essex Bay, and satellite settlements lined the Ipswich and Rowley rivers. Rowley, for example, had a settlement on Ox Pasture Brook near its juncture with the Parker River, adjacent to Ox Pasture Hill. The exact locations of Agawam and Wonasquam are explored further in the next question.

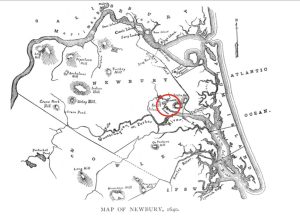

Village site of Kwaskwaikikwen

Quascacunquen was at the junction of Little River with the Parker River in Newbury, in the shadow of Old Town Hill. The people planted on the southwest flanks of that hill. Nearby Kent’s Island was a ceremonial gathering place. Other recorded smaller settlements were at Crane Pond Hill and Indian Hill in West Newbury, and all along the Merrimack in Newburyport and at junctions with the Merrimack tributaries.

Quascacunquen was at the junction of Little River with the Parker River in Newbury, in the shadow of Old Town Hill. The people planted on the southwest flanks of that hill. Nearby Kent’s Island was a ceremonial gathering place. Other recorded smaller settlements were at Crane Pond Hill and Indian Hill in West Newbury, and all along the Merrimack in Newburyport and at junctions with the Merrimack tributaries.

Village site of Cochichewicket

A principal village in North Andover was called Chochichewicket, located on the Cochichewick River, a tributary to the Merrimack, at the outflow of Lake Cochichewick, on the southwest side of Weir Hill, adjacent to a former swamp. The Indian deed to Andover includes a waiver allowing “Roger” to stay and occupy 6 acres of waterway and land in southern Andover with rights “to fish and to plant”. His existence in this place is retained today in the place name “Rogers Brook”.

A principal village in North Andover was called Chochichewicket, located on the Cochichewick River, a tributary to the Merrimack, at the outflow of Lake Cochichewick, on the southwest side of Weir Hill, adjacent to a former swamp. The Indian deed to Andover includes a waiver allowing “Roger” to stay and occupy 6 acres of waterway and land in southern Andover with rights “to fish and to plant”. His existence in this place is retained today in the place name “Rogers Brook”.

Village site of Nahumkeak

The Pawtucket village of Naumkeag, or Nahumkeak, was located at the outflow of the Bass River (the Wahquack) from Wenham Lake (Great Pond), adjacent to Cherry Hill and a swamp. They planted on “The Plains” just to the west and had satellite settlements and camps along the Miles River, Beaver Pond, and Frost fish Brook. The Dorchester Company survivors who became the “Old Planters” established Salem Village just to the south of this Pawtucket village.

The Pawtucket village of Naumkeag, or Nahumkeak, was located at the outflow of the Bass River (the Wahquack) from Wenham Lake (Great Pond), adjacent to Cherry Hill and a swamp. They planted on “The Plains” just to the west and had satellite settlements and camps along the Miles River, Beaver Pond, and Frost fish Brook. The Dorchester Company survivors who became the “Old Planters” established Salem Village just to the south of this Pawtucket village.

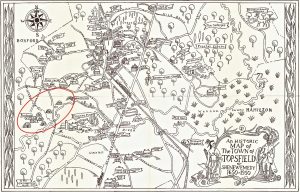

Village site of “Shenewemedy”

At the time of English settlement, the Pawtucket village of “Shenewemedy” in Topsfield was at the intersection of Fish Brook with the Ipswich River.

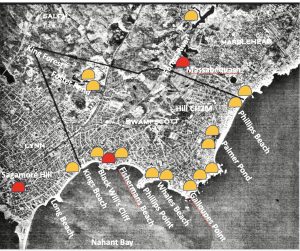

Camp sites in Squompscut

The Lynn-Swampscott shore was heavily populated in summers. Sagamore James, eldest son of Nanepashemet and Squaw Sachem, resided at Sagamore Hill in Lynn. Poquanum, or Black Will, of Nahant occupied a cliff on the Swampscott coast overlooking Nahant Bay; and Nanepashemet resided at Massabequash on the Forest River and summered in Marblehead.

In conclusion, despite little surviving physical evidence, the combined weight of geo-locational, ecological, documentary, linguistic, and ethnohistorical evidence for pre-Contact agricultural villages in Essex County is overwhelming. Samuel de Champlain and his shipmate Mark Lescarbot estimated in 1604 that the Pawtucket (whom they called the “Almouchiquois”) had been farming and fishing on the Essex county coast for at least 600 years, from around 1,000 CE (Common Era), based on their interviews with the sachems and sagamores they met on their explorations. And now I wonder: How did the Pawtucket on Cape Ann actually interact in their network of villages?

NEXT: Where exactly are Agawam and Wenesquawam?

Notes and References

[1] Lamson, D. F., 1895, History of the Town of Manchester, Essex County, Massachusetts 1645-1895, p. 1.

[2] The full quote, from John Joselyn (1674) is “Towns they have none, being always removing from one place to another for conveniency of food . . . I have seen half a hundred of their Wigwams together in a piece of ground and within a day or two, or a week they have all been dispersed.” Quoted in Chilton, ES, “”towns they have none”‘: Diverse subsistence and settlement strategies in native New England” (2002). NORTHEAST SUBSISTENCE-SETTLEMENT CHANGE: A,D, 700-1300. 126. Note, however, that by 1674 Indigenous communities had suffered depopulation and had been largely displaced by events leading up to King Philip’s War.

[3] The parenthetical source citations in this paragraph include the following:

Leavenworth, Peter S., 1999, “The Best Title That Indians Can Claime”: National Agency and Consent in the Transferal of Penacook-Pawtucket Land in the 17th Century, New England Quarterly 72 (2): 275-300.

McBride, Kevin A., 2002-2003, Transformation by Degree: Eighteenth Century Native American and Colonial Land Use. Cross Paths 5 (4).

Perley, Sidney, 1912, The Indian Land Titles of Essex County, Massachusetts, Essex Book and Print Club, Salem MA.

Wright, Harry Andrew, 1941, The Technique of Seventeenth Century Indian Land Purchases, Essex Institute Historical Collections 77: 185-197.

[4] This quote from John Josselyn is on p. 99 of his An Account of Two Voyages to New-England Made during the years 1638, 1663 (1674): http://archive.org/details/accountoftwovoya00joss.

[5] Moorehead’s maps appear in Moorehead, Warren K. and Benjamin L. Smith, Merrimack Archaeological Survey: A Preliminary Paper (1931), Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (Harvard University), Cambridge MA.

[6] The triangles on Moorehead’s maps represent settlement sites; X marks show the locations of shell middens, and crosses identify burial grounds.

[7] Coastal Algonquian trade with Europeans prior to exploration and later during settlement is documented in Kenneth Andrews’ 1984 book. Trade, Plunder, and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630 and Thomas Nixon’s 2011 book, The North American Fur Trade and its Effects on the Native American Population and the Environment in North America. See also articles by Bruce Bourke and Ruth Whitehead (1985), Tarrentines and the Introduction of European Trade Goods in the Gulf of Maine. Ethnohistory 32 (4): 327-341; and Dean Snow (1976), The Abenaki fur trade in the sixteenth century, The Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology. 6 (1): 3-11.

[8] For definitions of modes of subsistence and their socioeconomic correlates, as defined by cultural anthropologists, see: http://wikieducator.org/Cultural_Anthropology/Social_Institutions/Subsistence_Strategies. A perspective on the implications of a mixed economy for Native Americans of New England is given by Elizabeth Chilton (2002) in ‘Towns they have none’: Diverse subsistence and settlement strategies in Native New England, In J. Hart and C. Reith, eds. Northeast subsistence-settlement change: A.D.700 to A.D. 1700.

[9] The best sources of information about river drainage systems on the Atlantic coast are the websites of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (Our Waters, Wetlands, Watershed) and the U.S. Geological Survey (Interactive GIS Mapping Website for Major Drainage Basins in Massachusetts; National Geologic Map Database for Cape Ann).

[10] As noted by the ethnographer of the Pennacook, David Stewart-Smith (1994, 1999). For a perspective on the relationship between river drainage and settlement patterns, see James Bradley’s 2007 article, PaleoIndian Sites and Finds in the Lower Merrimac River Drainage (Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 68 (1): 12-20); the Climate Change Institute’s PaleoIndian Mobility and Aggregation Patterns; William Ritchie and Robert Funk’s Aboriginal settlement patterns in the Northeast (1973); Bruce Bourke’s 1973 article, Aboriginal Settlement and Subsistence on the Maine Coast (Man in the Northeast, No. 4: 3-20); and James Petersen and Ellen Cowie’s 2002 article, From hunter-gatherer camp to agricultural village: Late prehistoric indigenous subsistence and settlement (In Hart and Reith, Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change A.D. 700-1300).

[11] The websites of the U.S. Geological Survey, Environmental Protection Agency, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Climate Change Institute provide basic information on the historical geology of Essex County, such as the embayment of its rivers and formation of estuaries with salt marshes and barrier beaches. A technical example may be found in Hein et al. 2006 Holocene Sedimentary Evolution of the Merrimack Embayment, Western Gulf of Maine (Merrimack River Geology pdf). William Cronon, in his classic work Changes in the Land describes the significance of estuaries as a bioregion for both native and colonial habitation. For a local application, see Ed Bell’s 2009 paper, Cultural resources on the New England coast and continental shelf: Research, regulatory, and ethical considerations from a Massachusetts perspective, in Coastal Management 37:17-53.

[12] Bennett, M. K. 1955. The food economy of the New England Indians, 1605-1675. Journal of Political Economy 63(5): 369-397. Also Doughty, Christopher E. 2010. The development of agriculture in the Americas: An ecological perspective. Ecosphere 1: 21. Washington, DC: Ecological Society of America.

[13] For a perspective on Iroquois specialization in agriculture, see https://theiroquoisstory.weebly.com/iroquois-food-and-agriculture.html.

[14] That Native Americans favored estuarine environments because of the abundance and reliability of subsistence resources is well attested in the archaeological literature. See, for example Louis Brennan’s 1979 article, Coastal adaptation in prehistoric New England. American Antiquity 41 (1): 112-113, and an article by Elizabeth Chilton in 2002 (‘Towns they have none’: Diverse subsistence and settlement strategies in Native New England, in J. Hart and C. Reith, eds. Northeast subsistence-settlement change: A.D.700 to A.D. 1700). Differences in coastal and inland native settlement patterns in New England are also explained in Curtiss Hoffman’s 1989 article, Figure and ground: The late woodland village problem as seen from the uplands. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 50 (1) 24-28. Classic accounts of plant and animal species present in the estuaries of the Northeast appear in Champlain’s accounts and John Smith’s A Description of New England (1616), Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s Relation (1622); William Wood’s New England’s Prospect (1634); Thomas Lechford’s Plain Dealing (1642); Edward Johnson’s Wonder-Working Providence (1654); Ferdinando Gorges’ America Painted to the Life (1659); Samuel Maverick’s A Briefe Description of New England (1660); and John Josselyn’s New England’s Rarities Discovered in birds, beasts, fishes, serpents, and plants of that country (1674).

[15] I learned about the locational criteria for the siting of villages in coastal Massachusetts at a talk given by Kerry Lynch, University of Massachusetts Archaeological Services, “Identifying the Submerged Native American History of the Northeast: The Archaeology of Inundated Occupations”. She gave this talk on April 11, 2012 at the Weston Observatory in Weston, MA.

[16] Elizabeth Chilton (2010) explores the concept of mobile farming in Mobile farmers and sedentary models: Horticulture and cultural transitions in Late Woodland and contact period New England, in Susan Alt, ed., Ancient Complexities: New Perspectives in Precolumbian North America: 96-103. See also Robert Hasenstab (1999), Fishing, Farming, and Finding the Village Sites: Centering Late Woodland New England Algonquians, in The Archaeological Northeast: 139-153, and Barbara Luedtke (1988), Where are the late woodland villages in eastern Massachusetts? Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 49 (2) 58-65.

[17] See, for example, Lepionka and Gondola, Predictive models for locating inland and coastal villages in Northern Essex and Middlesex Counties, Massachusetts, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 83 (1-2): 77-88. Aside from Dunton’s letter of 1686 and the Pool Papers, direct reference to the Pawtucket village of Wonasquam in Gloucester by name appears in Bright (2002), pp. 41, 571; Williamson (Maine 1831), pp. 511-512; Gookin (1792), p. 177; and Schoolcraft (1855), pp. 221-224.

[18] From Lepionka and Gondola 2022.

[19] The original name of Gloucester’s Middle Street was Cornhill Street.

[20] Courtesy Southern Essex County Registry of Deeds. On these maps the turquoise lines represent canoe routes, and the green lines represent overland trails.

[21] The archaeoastronomy of Pole Hill is taken up in another context. See Lepionka, Mary Ellen and Mark Carlotto (2015), Evidence of a Native American Solar Observatory on Sunset Hill in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 76 (1): 27-42. Documentary evidence for Wonasquam in Gloucester includes direct references to this village in the following sources:

[22] See my 2020 article, Native Agricultural Villages in Essex County: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Evidence, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 81 (1-2): 65-90. On the map of map village sites in Essex County, the open circles denote settlements whose Algonquian names have been lost.

[23] Agawam (including Castle Neck) and other locations in Ipswich (e.g., Turkey Hill, Eagle Hill, Bull Brook, Indian Ridge, Great Neck) have long and very rich archaeological histories with major collections principally at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, the Ipswich Museum, and the Harvard Peabody Museum in Cambridge. The Trustees of Reservations owns the site of Agawam Village, which is on the Crane Reservation at Wigwam Hill, but for years their literature for visitors did not describe the rich Native history there, presumably for fear of looting.

[24] The parenthetical source citations in this section include the following:

Abbott, Abiel, 1829, History of Andover: From Its Settlement to 1829. Flagg and Gould, Andover MA.

Choate, Rufus, 1890, Indian Life at Chebacco, Echo, July 31, 1890, Essex MA.

Davis, Margo, 1996, Archaeological Potential of the Crane Reservations, Ipswich, Massachusetts: http://www.thetrustees.org/assets/documents/placestovisit/managementplans/NE_CastleHill_MP2007.pdf.

Dunton, John, 1686, Letters Written from New England, Prince Society Publications Issue 4, Ayer Publishing, North Stratford NH.

Felt, Joseph B., 1827, Annals of Salem, from Its First Settlement, Volume I. Shattuck Library: https://archive.org/details/annalsofsalemfro00jose

Hubbard, William, 1680, A General history of New England: from the discovery to 1680, Volume 5 of Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Hilliard & Metcalf, Boston.

LeBaron, J. Francis, 1874, Archaeological Atlas of Castle Neck, Ipswich, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem MA.

Pool, Ebenezer, 1823, Pool Papers, Vol. I. Typescript Mss. in the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA (original is in the basement of the Sandy Bay Historical Society, Rockport, MA).

Webber, Carl and Winfield S. Nevins, 1877, Old Naumkeag: An Historical Sketch of the City of Salem, and the Towns of Marblehead, Peabody, Danvers, Wenham, Manchester, Topsfield, and Middleton, A. A. Smith, Salem MA.

Winslow, Edward, 1624, Good Newes from New England: A true relation of things very remarkable at the Plantation of Plimoth in New England, 1996 reprint, Applewood Books, Carlisle MA