The Quest for Norumbega

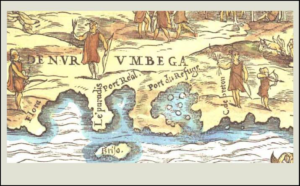

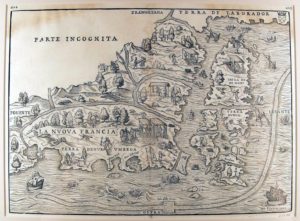

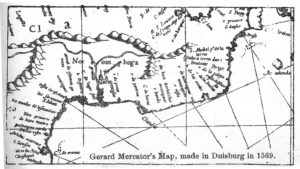

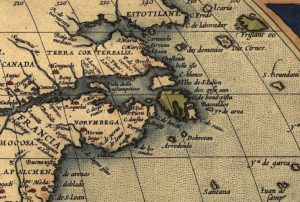

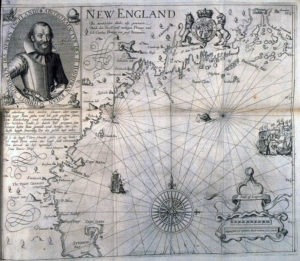

Fifteenth and sixteenth-century mapmakers did not have the benefit of the modern science of geodesy or global positioning systems based on satellite technologies. They did not even have the advantage of the sextant, a device invented in the late 17th century that used mirrors to measure the altitude of any object above the horizon line. Latitudes were well known, but longitude was a complex measurement and completely relative in the absence of a standard prime meridian. In addition to technical distortions, explorers’ interests, loyalties, and employers influenced what mapmakers portrayed on maps. Giovanni di Verrazano’s map of 1525, for example, reflected his desire to find silver in a city paradise the natives purportedly called Norumbega (or Norembega) and to discover a Northwest Passage to China through the Parte Incognita of the Americas. In 1542 Jacques Cartier, Jean Allefonsce, and other French explorers also described the fabulous “Indian kingdom” known as Norumbega. Maps claiming to show the location of Norumbega are as diverse as maps to El Dorado.14

1542 French Map with Norombega in Canada

Verrazano’s 1525 Map with Terra de Nurumbega in Southern New England

Mercator’s 1569 Map with Norombega on the Kennebec River

Ortelius’s 1570 Map with Norembega in Acadia

L’Escarbot’s 1606 Map with Norumbega on the Penobscot River

Like the cities of gold sought by the Spanish, Norumbega may have been a mythical place. It seems to have been somewhere in the homelands of the Abenaki, who might have been able to lead explorers to copper but not gold or silver. The “city” of Norumbega may have referred to the historically powerful Penobscot sachemship called Norridgewock at the junction of the Kennebec and Sandy rivers in Maine. Later American maps show Norembega on the Charles River. In the 1800s Dorchester, Charlestown, Watertown, Newton, and Cambridge all claimed to be the site of the fabled city. From 1897 until 1963 a beautiful amusement park operated in Newton-Auburndale called Norembega Park (and I was among the last to go dancing there to big band music in the famed Totem Pole Ballroom).15

The Totem Pole

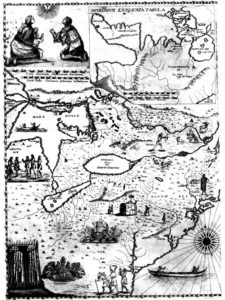

Other than silver, gold, the Northwest Passage, and Norumbega, old maps of the Northeast reveal early explorers’ hopes of finding copper on Maine’s coastal islands, sassafras on Cape Cod, peltry (furs) from Canada’s First Peoples, and Christian converts from wherever they could be found. Illustrated maps were used as advertisements for attracting investors in the fur trade, new missionaries, and sponsors for exploration.16

Bressani’s 1657 Map of Jesuit Missions and Converts

Explorers’ Perceptions of Indigenous Peoples

Early explorers recorded their observations and experiences with Indigenous Peoples, starting with Columbus and the Spanish missionaries. Initial impressions seem remarkably the same. Columbus wrote in his letter book:17

As I saw that they were very friendly to us, and perceived that they could be much more easily converted to our holy faith by gentle means than by force, I presented them with some red caps, and strings of beads to wear upon the neck, and many other trifles of small value, wherewith they were much delighted, and became wonderfully attached to us. Afterwards they came swimming to the boats, bringing parrots, balls of cotton thread, javelins, and many other things which they exchanged for articles we gave them, such as glass beads, and hawk’s bells [small jingle bells used in falconry]; which trade was carried on with the utmost good will. But they seemed on the whole to me, to be a very poor people. They all go completely naked, even the women, though I saw but one girl. All whom I saw were young, not above thirty years of age, well made, with fine shapes and faces; their hair short, and coarse like that of a horse’s tail, combed toward the forehead, except a small portion which they suffer to hang down behind, and never cut. Some paint themselves with black…; others with white, others with red….Some paint the face, and some the whole body; others only the eyes, and others the nose. Weapons they have none, nor are acquainted with them, for I showed them swords which they grasped by the blades, and cut themselves through ignorance. They have no iron, their javelins being without it, and nothing more than sticks, though some have fish-bones or other things at the ends. They are all of a good size and stature, and handsomely formed. I saw some with scars of wounds upon their bodies, and demanded by signs the [cause] of them; they answered me in the same way, that there came people from the other islands in the neighborhood who endeavored to make prisoners of them, and they defended themselves. I thought then, and still believe, that these were from the continent. It appears to me, that the people are ingenious, and would be good servants and I am of opinion that they would very readily become Christians, as they appear to have no religion. They very quickly learn such words as are spoken to them. If it please our Lord, I intend at my return to carry home six of them to your Highnesses, that they may learn our language.

Columbus Fleet Meets the Arawakan Taino, 1492

Verrazano’s description of Indigenous people on the Carolina coast, who were Algonquians, offers similar details:18

…Many people who were seen coming to the sea-side fled at our approach, but occasionally stopping, they looked back upon us with astonishment, and some were at length induced, by various friendly signs, to come to us.

These showed the greatest delight on beholding us, wondering at our dress, countenances and complexion. They then showed us by signs where we could more conveniently secure our boat, and offered us some of their provisions. That your Majesty may know all that we learned, while on shore, of their manners and customs of life, I will relate what we saw as briefly as possible. They go entirely naked, except that about the loins their wear skins of small animals like martens fastened by a girdle of plaited grass, to which they tie, all round the body, the tails of other animals hanging down to the knees; all other parts of the body and the head are naked. Some wear garlands similar to birds’ feathers…. The complexion of these people is black, not much different from that of the Ethiopians; their hair is black and thick, and not very long, it is worn tied back upon the head in the form of a little tail. In person they are of good proportions, of middle stature, a little above our own, broad across the breast, strong in the arms, and well formed in the legs and other parts of the body….

A hundred years after Columbus and Verrazano and before Champlain came to Le Beauport (roughly between 1540 and 1605), other explorers visited the coasts of Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. For example, in 1579 John Walker sailed with Simon Ferdinando for Sir Humphrey Gilbert to anchor in Penobscot Bay and met with Abenaki aboard his flagship. He is alleged to have taken 200 dried moose hides from an unattended storage site, suggesting that the Abenaki were already heavily involved in the fur trade by that time. Henry Hudson and Samuel Argall further explored the Penobscot River in 1609 and 1610 respectively.19

In 1583 Edward Hayes sailed to St. Johns with Humphrey Gilbert to claim Newfoundland for England. They discovered already well-established entrepreneurial French, Basque, Portuguese, and English fishing stations and sheep farms. Hayes’s account describes how they attempted to extend English sovereignty (e.g., you could get your ears cut off if you bad-mouthed Queen Elizabeth) and how on the return voyage Hayes’s ship the Golden Hind became the sole surviving vessel in a fleet of seven. Hayes wrote:20

We were in number in all about 260 men; among whom we had of every faculty good choice, as shipwrights, masons, carpenters, smiths, and such like, requisite to such an action; also mineral men and refiners. Besides, for solace of our people, and allurement of the savages, we were provided of music in good variety; not omitting the least toys, as morris-dancers, hobby-horse, and May-like conceits to delight the savage people, whom we intended to win by all fair means possible. And to that end we were indifferently furnished of all petty haberdashery wares to barter with those simple people.

In 1534 Cartier met the Beothuk of Labrador and Newfoundland, now said to be extinct. The Beothuk were non-agricultural, predated Algonquian occupation, did not speak an Algonquian language, and were seacoast-specialized. They were also noted for their ferocity and their extensive use of red ochre. Europeans were impressed with Beothuk stature and their ocean-going canoes, adapted for the sea with high gunwales, and with their ability to hunt marine mammals, including seals, porpoises, and whales. After a brief encounter, however, the Beothuk attacked to expel the Europeans, whom they saw, rightly, as invaders.21

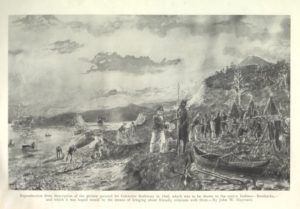

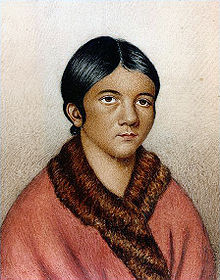

Cartier Fleet Makes Contact with Beothuk in Newfoundland

What Happened to the Beothuk?

Cartier described the Beothuk as “red men” because of the red ochre they used as a protective coating on their skin. It’s claimed that’s how the term “redskins” subsequently got applied to all Indigenous Peoples of North America. In his account of his voyage of 1534, Cartier describes how the Beothuk rubbed red ochre on everything—their bodies, hair, shelters, clothing, and implements. French contact was limited, however, because of Beothuk hostility and complete disinterest in the fur trade.22

Vikings may have had a similar experience with the Beothuk more than 500 years earlier. The skraelings (“false friends”, pronounced skray lingz), described in the Norse Sagas, attacked the Eriksons’ attempted settlements in Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia. Skraelings may have included the Beothuk as well as the Innu and the Thule, ancestors of the present-day Naskapi and Inuit peoples respectively.

Over the next three hundred years, as their cod fisheries, colonies, and slave trade grew, the Europeans and their Indigenous allies brought the surviving Beothuk of Newfoundland to near extinction. The English recorded the last-known individuals as the captive women Demasduit and Shanawdithit, their stories all the more tragic because they could not have been returned to their people. The fierce Beothuk reportedly sacrificially killed all individuals who had any, even unwilling, contact with their enemies.23

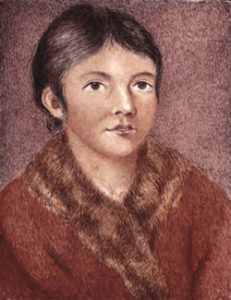

Demasduit (Mary March) was kidnapped by John Peyton Jr. in 1819 in an ambush that killed her husband and led to the death of her infant son. Lady Henrietta Hamilton painted a portrait of her before the Beothuk woman died of tuberculosis the following year. In 1823 Demasduit’s niece, Shanawdithit, and Shanawdithit’s sister and mother, all their kin gone, came out of hiding for protection, surrendering to an English trapper living nearby. Shanawdithit died of tuberculosis in 1829 as “the last” recorded Beothuk. In 1841 William Gosse made a posthumous painting of Shanawdithit (Nancy April), which clearly borrows from the earlier portrait.24

Demasduit and Shanawdithit

Although these women were memorialized as the last of their people, other Beothuk no doubt had survived by joining Mi’Kmaq settlements or marrying into other Abenaki groups during the 17th and 18th centuries. Maybe Beothuk warriors were among the Mi’Kmaq whom the Penobscot, Pawtucket, Pennacook, and Massachuset later feared as the dreaded Tarrantines. Cartier refers to helping the Almouchiquois (Algonquians) against their enemy “the Terentynes”.

Pring, Gosnold, and Weymouth

Martin Pring in the Speedwell; Robert Salterne in the Explorer; and Gabriel Archer, John Brereton and Bartholomew Gosnold in the Concord all wrote accounts of their New World encounters. Like other explorers before them, they sailed on several voyages in mix-and-match fleets under noble or royal or merchant sponsorship on missions of discovery, procurement of commodities, or colonization. Pring, for example, was in New England in 1602 looking for a site for a colony, again in 1603 looking for sassafras for Bristol merchants, and again in 1606 looking to establish fur trading posts on the Saco and Penobscot rivers.25

History tends to oversimplify and condense such voyages, conflating ships’ captains with the explorers and their supercargo: companions, navigators, mapmakers, patent holders, sponsors, or monarchs. Historical statements such as “Gosnold landed on the coast of Maine” elevates the individual man and the achievement of landfall, obscuring the fact that several ships with hundreds of men on several voyages with several landfalls were involved and that Gosnold was not acting alone or even necessarily on his own initiative. Perhaps this is a human thing—how heroes and legends are cut away from the solid mountain of facts of the past and are carved and polished into the stand-alone monuments we like to celebrate.

In 1602, Gosnold got travel directions from Native Americans at a place he called “Savage’s Rock”, which, contrary to local speculation, probably was not on Cape Ann. The landing site is believed to have been Cape Neddick at York Beach, Maine, or Cape Porpoise at Kennebunkport, based on the Concord’s nautical data. They reported reaching Savage’s Rock at a little over 43 degrees north latitude, and that when they left they reached Cape Cod after fourteen or fifteen hours of sailing on a fresh breeze. Even by conservative estimates, they apparently would have overshot Cape Cod in that time if they had left from Cape Ann. So, the desire to have Gosnold here must, like the Vikings, be denied, though it should not matter. The Pennacook Gosnold parlayed with in Maine no doubt fished here.26

Gosnold Fleet Meets Pennacook Near Agawam in 1602

The Indigenous people whom Gosnold, Brereton, and Archer encountered in Maine (and others encountered on the Piscataqua, Saco, Kennebec, and Penobscot rivers) undoubtedly were Pennacook or other Abenaki involved in trade with the French. With a piece of chalk Gosnold gave them, on the bedrock the Abenaki drew a map of the Massachusetts coast, including Cape Cod and the islands, which Gosnold reported to be completely accurate. A few years later, the Pawtucket at Le Beauport similarly drew an accurate map for Champlain, including the islands of Boston Harbor and the six Massachuset sachemships, as described previously. One wonders if the Gosnold and Champlain accounts about “Indians” drawing maps on rock could actually be a conflation of one event.27

From Brereton’s report:28

[On] Friday, the fourteenth of May [May 24, 1602, New Style], early in the morning, we made the land, being full of fair trees, the land somewhat low, certain hummocks or hills lying into the land, the shore full of white sand, but very stony or rocky. And standing fair alongst by the shore, about twelve of the clock the same day, we came to an anchor, where eight Indians, in a Basque shallop with mast and sail, an iron grapple, and a kettle of Copper, came boldly aboard us, one of them appareled with a waistcoat and breeches of black serge, made after our sea-fashion, hose and shoes on his feet; all the rest (saving one that had a pair of breeches of blue cloth) were naked….These people are of tall stature, broad and grim visage, of a black swart complexion, their eyebrows painted white; their weapons are bows and arrows. It seemed by some words and signs they made, that some Basques, or of Saint John de Luz [Basques of Spain or France], have fished or traded in this place, being in the latitude of 43 Degrees (p. 2)…. [We] saw many Indians, which are tall big boned men, all naked, saving they cover their privy parts with a black tewed [tanned] skin, much like a Blacksmiths apron, tied about the middle and between their legs behind: they gave us of their fish ready boiled…whereof we did eat…they gave us also of their Tobacco….( p. 4). These people, as they are exceeding courteous, gentle of disposition, and well conditioned, excelling all others that we have seen; so for shape of body and lovely favor, I think they excel all the people of America; of stature much higher than we; of complexion or color, much like a dark Olive; their eyebrows and hair black, which they wear long, tied up behind in knots, whereon they prick feathers of fowls, in fashion of a crownet: some of them are black thin bearded; they make beards of the hair of beasts: and one of them offered a beard of their making to one of our sailors, for this that grew on his face, which because it was of a red color, they judged it to be none of his own. They are quick eyed, and steadfast in the looks, fearless of others harms, as intending none themselves; some of the meaner sort given to filching, which the very name of Savages (not weighing their ignorance in good or evil) may easily excuse: their garments are of Deer skins, and some of them wear Furs round and close about their necks…. Their women (such as we saw) which were but three in all, were but low of stature, their eyebrows, hair, apparel, and manner of wearing, like to the men, fat, and well favored, and much delighted in our company; the men are dutiful towards them (p. 8).

Gosnold wrote in a letter to his father:29

We cannot gather, by anything we could observe in the people, or by any trial we had thereof ourselves, but that it is as healthful a climate as any can be. The inhabitants there, as I wrote before, being of tall stature, comely proportion, strong, active, and some of good years, and as it should seem very healthful, are sufficient proof of the healthfulness of the place.

Gosnold and his gentlemen adventurers wrote glowing accounts of good relations with the Algonquian peoples they encountered. Unlike the voyagers searching for treasure or a Northwest Passage, they were en route to try to establish a plantation on Cape Cod. Others were less respectful. In his 1603 voyage, Martin Pring kidnapped some Abenaki on the Saco and Penobscot rivers to bring home to his sponsors. In his 1606 voyage, sailing for Sir Ferdinando Gorges, he reported that villages along the Piscataqua (Portsmouth, NH) had been abandoned. George Waymouth (Weymouth), sailing for Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1605 to find a site for a plantation on the southern coast of Maine, had also kidnapped Abenaki to bring home. On subsequent voyages Pring and other explorers carried a captive with them to serve as an interpreter and guide. Champlain, too, was a beneficiary of this practice.30

Looking for sassafras to treat a growing number of syphilis cases back home, Pring explored the New England coast in 1603 and made landfall at Plymouth Harbor. As described to Richard Hakluyt in an account preserved by Samuel Purchas:31

During our abode on the shore, the people of the Countrey came to our men sometimes ten, twentie, fortie, or threescore, and at one time one hundred and twentie at once. We used them kindly, and gave them divers sorts of our meanest Merchandise. They did eat Pease and Beanes with our men. Their owne victuals were most of fish….These people in colour are inclined to a swart, tawnie, or Chestnut colour, not by nature but accidentally, and doe weare their haire brayded in foure parts, and trussed up about their heads with a small knot behind: in which haire of theirs they sticke many feathers and toyes for braverie and pleasure. They cover their privities only with a piece of leather drawne betwixt their twists and fastened to their Girdles behind and before: whereunto they hang their bags of Tobacco. They seeme to bee somewhat jealous of their women, for we saw not past two of them, who weare Aprons of Leather skins before them downe to the knees, and a Beares skinne like an Irish Mantle over one shoulder. The men are of stature somewhat taller than our ordinary people, strong, swift, well proportioned, and given to treacherie, as in the end we perceived….

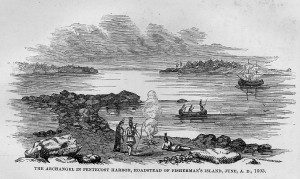

James Rosier wrote an account of his 1605 voyage on the Archangell with George Weymouth to Monhegan Island and the coast of Maine, which they called “the northern part of Virginia”. They were looking for a site for a fishing plantation and opportunities to trade for furs. According to Rosier’s description of their first contact with Native Americans:32

On May 30…about five a clocke in the afternoone, we in the shippe espied three Canoas [canoes] comming towards us, which went to the island adjoining, where they went a shore, and very quickly had made a fire, about which they stood beholding our ship: to whom we made signes with our hands and hats, weffing unto them to come unto vs, because we had not seene any of the people yet. They sent one Canoa with three men, one of which, when they came neere unto us, spake in his language very lowd and very boldly: seeming as though he would know why we were there, and by pointing with his oare towards the sea, we conjectured he meant we should be gone. But when we shewed them knives and their use, by cutting of stickes and other trifles, as combs and glasses, they came close aboard our ship, as desirous to entertaine our friendship. To these we gave such things as we perceived they liked, when wee shewed them the use: bracelets, rings, peacocke feathers, which they stucke in their haire, and Tabacco pipes. After their departure to their company on the shore, presently came foure other in another Canoa: to whom we gave as to the former, using them with as much kindnes as we could….The shape of their body is very proportionable, they are wel countenanced, not very tal nor big, but in stature like to us: they paint their bodies with blacke, their faces, some with red, some with blacke, and some with blew [blue]…. Their clothing is Beavers skins, or Deares skins, cast over them like a mantle, and hanging downe to their knees, made fast together upon the shoulder with leather; some of them had sleeves, most had none; some had buskins [boots] of such leather tewed: they have besides a peece of Beauers skin betweene their legs, made fast about their waste, to cover their privities….They suffer no haire to grow on their faces, but on their head very long and very blacke, which those that have wives, binde up behinde with a leather string, in a long round knot. They seemed all very civill and merrie: shewing tokens of much thankefulnesse, for those things we gave them. We found them then (as after) a people of exceeding good invention, quicke understanding and readie capacitie….

Then the next day:

[We] saw foure of their women, who stood behind them, as desirous to see us, but not willing to be seene; for before, whensoever we came on shore, they retired into the woods, whether it were in regard of their owne naturall modestie, being covered only as the men with the foresaid Beavers skins, or by the commanding jealousy of their husbands, which we rather suspected, because it is an inclination much noted to be in Salvages; wherefore we would by no meanes seeme to take any speciall notice of them. They were very well fauoured in proportion of countenance, though coloured blacke, low of stature, and fat, bare headed as the men, wearing their haire long: they had two little male children of a yeere and a half old, as we judged, very fat and of good countenances, which they love tenderly, all naked, except their legs, which were covered with thin leather buskins tewed, fastened with strops to a girdle about their waste, which they girde very straight, and is decked round about with little round peeces of red Copper; to these I gave chaines and bracelets, glasses, and other trifles, which the Salvages seemed to accept in great kindnesse.

Rosier goes on to describe how they then tricked and captured the five Abenaki at Pemaquid for Weymouth to bring back to England to his sponsors. Afterwards, Rosier observes:33

First, although at the time when we surprised them, they made their best resistance, not knowing our purpose, nor what we were, nor how we meant to use them; yet after perceiving by their kinde usage we intended them no harme, they have never since seemed discontented with us, but very tractable, loving, & willing by their best meanes to satisfie us in any thing we demand of them, by words or signes for their understanding: neither have they at any time beene at the least discord among themselves; insomuch as we have not seene them angry but merry; and so kinde, as if you give any thing to one of them, he will distribute part to every one of the rest.

The Archangell in Penobscot Bay in 1605

Popham and Capt. John Smith

Others followed, such as George Popham and Ralegh Gilbert, who sailed in two ships (Gift of God and Mary and John) with 120 people, including Skidwares, one of Weymouth’s Pemaquid captives. According to the chronicler, Skidwares promptly escaped upon repatriation to remain with his chief, Nahanada (or Dahanada), another captive who had previously been repatriated. In any case, Popham, sailing for the Virginia Company, carried a native captive as a guide. Encouraged by Pring’s findings the year before, Popham’s company was instructed to found a fishing colony, fur trading post, and a fort on the Kennebec River. This was in 1607, the same year that Jamestown was founded in Virginia. Popham Colony, also known as Sagadahoc, like Roanoke, was, however, short lived.34

1606 Newport, Smith, and the Jamestown Fleet Meet Powhatan in Virginia

Popham’s company built Fort St. George on the Kennebec but abandoned it after a year, mainly because of problems with sponsorship and authorization back home. A first-hand account describes the Popham fleet’s contact with Indigenous people at Pemaquid to the north:35

About midnight Captain Gilbert caused his ship’s boat to be manned with 14 persons and the Indian called Skidwares (brought into England by Captain Waymouth) and rowed to the westward, from their ship to the River of Pemaquid which they found to be 4 leagues distant from their ship where she rode. The Indian brought them to the savage’s houses, where they found 100 men, women, and children and their chief commander or sagamo, amongst them named Nahanada, who had been brought likewise into England by Captain Waymouth and returned thither by Captain Hanam setting forth for these parts, and some part of Canada the year before. At their first coming the Indians betook them to their arms, their bows and arrows, but after Nahanada had talked to Skidwares and perceived that they were Englishmen, he caused them to lay aside their bows and arrows, and he himself came unto them and embraced them and made them much welcome, and after 2 hours interchangeably thus spent, they returned aboard again. Captain Popham manned his shallop and Captain Gilbert his ship’s boat with 50 persons in both and departed for the River of Pemaquid, carrying with them Skidwares. Being arrived in the mouth of the river there came forth Nahanada with all his company of Indians with their bows and arrows in their hands, they being before his dwelling houses would not willingly have all our people come on shore, being fearful of us. To give them satisfaction the captains with some 8 or 10 of the chiefest landed, but after a little parley together they suffered all to come ashore using them in all kind sort after their manner. Nevertheless after one hour they all suddenly withdrew themselves into the woods, nor was Skidwares desirous to return with us any more aboard. Our people loath to offer any violence unto him by drawing him by force, suffered him to stay behind, promising to return unto them the day following, but he did not.

The writer of the account seems insensitive to the idea that the Abenaki sagamore and his warriors may have felt they had good reason to avoid further risk of abduction!

As an English observer, Popham noted strong French influence among the Eastern Abenaki and the Mi’Kmaq, their fierce leader Messamoet, and the Western Abenaki fear of them and other Tarrantines, such as those led by the dreaded Membertou of Nova Scotia. Henry Hudson, sailing for England to Penobscot Bay in 1609, also remarked on French hegemony on trade in Maine and the Maritimes. By Hudson’s account:36

The seventeenth, all was mystie, so that we could not get into the harbor. At ten of the clocke two boats came off to us, with sixe of the savages of the countrey, seeming glad of our coming. We gave them trifles, and they eate and dranke with us; and told us that there were gold, silver and copper mynes hard by us; and that the Frenchmen doe trade with them; which is very likely, for one of them spake some words of French. So wee rode still all day and all night, the weather continuing mystie.

Captain John Smith seems to have had ambiguous or mixed reactions to the Indigenous Peoples he encountered. His accounts express both admiration and contempt. He claimed friendship with an Abenaki sachem in Maine but advertised New England to merchant investors as a place well stocked with natives as a ready supply of forced labor, who were otherwise easily vanquished. Between 1607 and 1609, his militancy in helping to establish the Jamestown Colony caused enduring enmity between the English and the Algonquian people living there (the Pocahontas story notwithstanding).37

Smith mapped New England in 1614 when in the employ of the Plymouth Company to explore the coast for a possible fishing colony. Smith named Cape Ann Tragabigzanda and the Three Turks’ Heads (presumably the Thatcher, Straitsmouth, and Milk islands), based on his previous adventures in the Ottoman Empire. He was captured as a mercenary in the Austrian army, enslaved, and bought by a Turkish nobleman. The nobleman gave Smith to his mistress, a Greek girl. Her name means “Girl of Trebizond” and she was not a Turkish princess, nor Smith’s mistress, although she apparently showed him kindness. Smith eventually managed to escape by decapitating three Turks, hence the Turks’ Head islands. James I of England, allowed his son, the future Charles I, to rename Tragabigzanda Capa Anna (soon shortened to Cape Ann on most maps) in honor of his mother, Queen Anne of Denmark.38

John Smith and Detail from his 1616 Map of New England

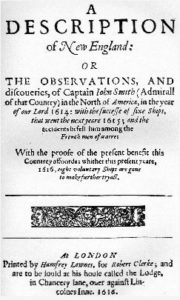

In A Description of New England (1616), Smith credits the discovery of New England to Sir Francis Drake (who, however, only saw the coast from Virginia south to the Caribbean). Smith also credits the previous voyages of Gosnold, Weymouth, Popham, and Hudson. These explorers, including Smith did not set foot on Cape Ann or the Essex County coast, however, and I have not been able to confirm any actual landings here prior to 1623 other than Champlain’s.39

According to Smith’s A Description of New England (1616):40

As you pass the Coast still Westward, Accominticus [Agamenticus, e.g., Rye and York, ME, explored by Bartholemew Gosnold in 1602] and Passataquack [Piscataqua River at Portsmouth, NH, explored by Martin Pring in 1603] are two convenient harbors for small barks; and a good Countrie, within their craggie cliffs. Angoam [Ipswich-Essex] is next; This place might content a right curious judgement: but there are many sands at the entrance of the harbor: and the worst is, it is inbayed too farre from the deepe Sea. Heere are many rising hilles, and on their tops and descents many corne fields, and delightfull groves. On the East, is an Ile of two or three leagues in length [Plum Island]; the one halfe, plaine morish grasse fit for pasture, with many faire high groves of mulberrie trees gardens: and there is also Okes, Pines, and other woods to make this place an excellent habitation, being a good and safe harbor. Naimkeck [Naumkeag, probably incorporating Cape Ann] though it be more rockie ground (for Angoam is sandie) not much inferior; neither for the harbor [Gloucester Harbor], nor any thing I could perceive, but the multitude of people. From hence doth stretch into the Sea the faire headland Tragabigzanda [Rockport], front with three Iles called the three Turks heads: to the North of this doth enter a great bay [?Sandy Bay or Ipswich Bay], where wee founde some habitations and corne fields: they report a great River [?the Merrimack], and at least thirtie habitations do possesse the Countrie. But because the French had got their trade, I had no leasure to discover it. The Iles of Mattahunts [Nahant] are on the West side of this Bay [Salem Sound to Nahant Bay], where are many Iles, and questionlesse good harbors: and then the Countrie of the Massachusets, which is the Paradise of all these parts: for here are many Iles all planted with corne; groves, mulberries, salvage [savage] gardens, and good harbors; the Coast is for the most part, high clayie sandie cliffs. The Sea Coast as you pass, shewes you all along large corne fields, and great troupes of well proportioned people: but the French having remained here neere sixe weekes, left nothing for us to take occasion to examine the inhabitants relations, viz. if there be neer three thousand people upon these Iles; and that the River doth pearce many daies journeys the intralles of that Countrey.

Smith’s use of local Algonquian place names in his account include Angoam, Aggawom (Agawam), and Naimineck (Naumkeag). These names do not appear in any of his predecessors’ accounts, and Smith reports explicitly that he did not go ashore to investigate on the coast of Massachusetts. Thus, they had to be names that Smith learned from his Abenaki host on his visit to Maine in 1614, when he stayed ashore on the Kennebec River long enough to plant and grow a garden. His informant must have been Dohannida (whose name Weymouth’s Rosier wrote as Nahanada and Popham’s chronicler as Tahaneda), the Abenaki sagamore or sachem whom Weymouth kidnapped at Pemaquid and brought to England in 1605 and whom Thomas Hanam returned to Maine in 1606. Smith claims to have befriended Dohannida during his stay in Maine, and the sagamore certainly would have been familiar with the place names of Algonquian territories and sagamoreships to his south.41

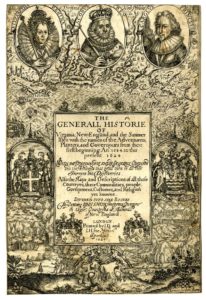

Interestingly, Angoam (or Aggowam), Naimkeck, and other names in Smith’s account are not shown on his 1614 map of New England. Also, one version of this map shows English settlements that had not yet been founded or named by 1616 when the map was first published, such as Salem, Ipswich, and Plimoth. The explanation may be that the map was edited for new editions or others of his works, such as his Generall Historie of Virginia, New England and the Summer Isles, published in 1624. Smith‘s writings apparently were enormously influential; after 1616, most voyagers, including the Mayflower fleet, used his map for navigation.42

Smith’s A Description of New England, 1616 and Generall Historie,1624

1624 Version of Smith’s Map

Smith’s “Dry Salvages”

Smith’s names for Cape Ann sites include the Dry Salvages (the last syllables rhyme with wages), islets off Straitsmouth. The meaning is unclear except that part of the rock outcrop is above the tide line and therefore dry, while another part (Little Salvages) is submerged at high tide. Smith wrote salvages for “savages”, from the French sauvage. Since he tended to see islands as heads or caps, with his mordant sense of humor perhaps he meant the heads of Algonquian swimmers, some wet or drowned and some dry. He bragged about shooting Indians in the water as they swam. In any case, the Dry Salvages were the inspiration for a poem by T. S. Eliot, who learned to sail in Gloucester during his youth. At risk of digression, here is an excerpt from “The Dry Salvages,” the 3rd Poem of Eliot’s Quartets, 1941:43

The river is within us, the sea is all about us;

The sea is the land’s edge also, the granite

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation:

The starfish, the hermit crab, the whale’s backbone;

The pools where it offers to our curiosity

The more delicate algae and the sea anemone.

It tosses up our losses, the torn seine,

The shattered lobsterpot, the broken oar

And the gear of foreign dead men.

The sea has many voices,

Many gods and many voices.

The salt is on the briar rose,

The fog is in the fir trees.

The sea howl

And the sea yelp, are different voices

Often together heard; the whine in the rigging,

The menace and caress of wave that breaks on water,

The distant rote in the granite teeth,

And the wailing warning from the approaching headland

Are all sea voices, and the heaving groaner

Rounded homewards, and the seagull:

And under the oppression of the silent fog

The tolling bell

Measures time not our time, rung by the unhurried

Ground swell, a time

Older than the time of chronometers, older

Than time counted by anxious worried women

Lying awake, calculating the future,

Trying to unweave, unwind, unravel

And piece together the past and the future,

Between midnight and dawn, when the past is all deception,

The future futureless, before the morning watch

When time stops and time is never ending;

And the ground swell, that is and was from the beginning,

Clangs the bell.

Aground on the Dry Salvages

Studying history, it does seem sometimes that “the past is all deception” and time does not really pass, but endlessly repeats.

So, this is all who came here, to answer this chapter’s question. What they all saw in the Algonquians and other Indigenous Peoples, to put it bluntly, was primitive people of imposing stature and physique and some admirable qualities who nevertheless were racially, morally, and technologically inferior and therefore easily exploitable for goods and services or as commodities themselves. And now we must ask, what about those people? Especially: What were the Pawtucket like? How were they organized and led? How did they respond to European settlement?

Next: How Were the Pawtucket Organized and Led?

Notes and References

- That Vikings were very likely the first European discoverers of North America is well established. Claims about Vikings on Cape Ann, however, are not, although they are repeated in The Gloucester Massachusetts Historical Time-Line 1000-1999 compiled by Mary Ray and edited by Sarah Dunlap, published locally in 2000. The claims are referenced to a 19th century local publicist and amateur historian, Robert Pringle, and to a secondary source that cites Cape Cod as the Viking landing site in New England, not Cape Ann. Historians of Cape Ann writing prior to 1892 do not mention Vikings here. The translations of the Icelandic Sagas that I consulted for this chapter include the 3rd edition of B. F. DeCosta’s 1901 The Pre-Columbian Discovery of America by the Northmen: Translations from the Icelandic Sagas, and the Rasmus B. Anderson translation of The Younger Edda (also Snorre’s Edda, The Prose Edda) by Snorre Snorri Sturluson, written in 1220. See http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/18947. A classic secondary (although not necessarily authoritative) source is Samuel Eliot Morison’s The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages.

- Pringle’s Souvenir History of Gloucester Mass 1623-1892, or History of the Town and City of Gloucester, Cape Ann, Massachusetts contains unverified information on Vikings and other subjects. For more information on interpreting the meanings of Old Norse and Old Icelandic words and on determining the location of places described in the language of the Vikings, see http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/saga.htm and http://www.mnh.si.edu/vikings/voyage/subset/vinland/environment.html. Read about the confirmed Viking UNESCO World Heritage Site in Newfoundland, L’Anse aux Meadows, at http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/4. For a review of all the candidates for Thorvald’s (Leif’s bother’s) burial place, see Graeme Davis’s 2009 book, Vikings in America.

- See, for example, Abraham Ortelius’s 1570 Map of the Americas on the Wikipedia Commons: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NorthEastAmericaOrtelius1570.jpg#file. Note that on the Viking map, Vinland is the pointed north-facing cape, shown as an extension of Greenland (Gronlandia). It certainly is not Cape Ann, and if it is Cape Cod, then the explorers encountered the Skraelings somewhere along Massachusetts Bay and Cape Ann is somewhere en route to Marchland. However, a glance at the long and rugged coastline of the Maritime Provinces and the Gulf of Maine shows a host of other candidates for capes of all kinds fitting Viking descriptions. Ortelius’s map, meanwhile, includes Iceland, Greenland, Baffin Island, and portions of Labrador and Newfoundland, along with some fictional islands. It shows no Scandinavian explorations or settlements below 55 degrees north latitude.

- Krossanes (more properly Krossarnes) means “Cross Point” and refers to the point of land between two fjords where their waters cross as they meet the sea. Sites on the New England coast do not meet this criterion. Hampton, NH, had “Thorvald’s grave” encased to protect it from souvenir-seeking tourists, who would hack off pieces of the rock. The scratches on the stone, interpreted as Norse runes, were more likely made by Algonquians. The Hampton NH claim is debunked on several grounds, for example, in David Craig’s article, Thorwald’s Grave: Fact or Legend? in New Hampshire Profiles 23 (1), 1974. Alleged runestones in New England also have not been substantiated. “Runes” such as some that appear on Dighton Rock in Massachusetts are Native American petroglyphs, while others, such as the Kensington Stone in Minnesota, have been proven to be frauds. Likewise, claims that Algonquians were incapable of building Celt-like megalithic structures or stone structures employing lintels are demonstrably false. Read a critical review of other Viking site claims in Viking America: the First Millennium (2001) by Geraldine Barnes. In contrast, a popularization of the “mystery” of Vikings on Cape Cod is perpetuated in Robert Cahill’s New England’s Viking and Indian Wars (1986). Petroglyphs on the Hamden NH “headstone” and on Deighton Rock resemble Indigenous inscriptions on other rockfaces and boulders in the Northeast.

- Rasmus Anderson, son of Norwegian immigrants, popularized the idea of a Leif Erikson Day commemorating Vikings in America in his influential 1877 book, America Not Discovered by Columbus. Another great enthusiast was Bostonian Eben Norton Horsford. On October 29, 1887, at Faneuil Hall Horsford gave an address, “The Discovery of America by Northmen”, at the dedication of a statue of Leif Erikson. For more information about the Chicago’s World Fair and the ship The Viking, see The Book of the Fair: World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in the Paul V. Galvin Library Digital History Collection at http://columbus.iit.edu/bookfair/ch17.html.

- The Scandinavian Fraternity of America (1915-1992) was a consolidation of previously founded organizations during the heyday of ethnic/immigrant fraternal associations in America, including the Scandinavian-American Fraternity (1893-1918) and others established in the 1870s.

- The story of Thorvald’s death and burial is told in the Groenlendiga Saga (Greenlander’s Saga) from the Flateyjarbók (Flat-Island Book), written about 1387. Contrary to Robert Pringle’s imagination, the Thorvald Hotel on Bass Rocks in Gloucester almost certainly did not mark the spot. In Einar Haugen’s 1942 translation (Voyages to Vinland: The First American Saga), Thorvald and a crew of 40 men set out in 1004 to further explore Vinland. The first summer they sail west from Leif’s camp in Vinland and discover “a lovely, wooded country” in which “the woods ran almost down to the sea, with a white, sandy beach. The sea was full of islands and great shallows.” Then, in the second summer they sail eastward from Leif’s camp and “along the coast to the north. As they were rounding “a certain cape”, a stiff storm fell upon them and drove them on shore, so that their keel was broken and they had to stay there a long time while they repaired the ship. Then Thorvald said to his men, ‘I wish we might raise up the keel on this cape and call the cape Keelness (Kjalarnes), and so they did. Then they sailed along the coast to the east, into some nearby fjord mouths, and headed for a jutting cape that rose high out of the sea and was all covered with woods. Here they anchored the ship and laid down a gangplank to the shore. Thorvald went ashore with all his company. Then he said, ‘This is beautiful, and here I should like to build me a home.’ After a time they went back to the ship. Then they caught sight of three little mounds on the sand farther in on the cape. When they got closer to them, they saw three skin-covered boats, with three men under each. They split up their force and seized all the men but one, who escaped in his boat. They killed all eight of them, and then returned to the cape. …” The men sleep after the killing spree and then on a premonition run to their ship. They discover they are under attack from “a host of boats…heading towards them from the inner end of the fjord.” A battle ensues and Thorvald is wounded in the armpit by an arrow. He says to his men, “This will be the last of me. Now I advise you to make ready for your return as quickly as possible. But me you shall take back to that cape which I found so inviting. It looks as if I spoke the truth without knowing it when I said that I might live there some day! Bury me there with a cross at my head and another at my feet, and ever after you shall call it Crossness (Krossarnes)”. And on this thread hangs the tale of a Viking grave in Gloucester. The reference to crosses may have been added to this saga at a later time. Thorvald’s was the first generation of Erikisens to fully embrace Christianity.

- As the Saga continues, in his attempt to retrieve his brother Thorvald’s body, Thorstein can’t locate Vinland. Thorfinn Karlsnefni, referenced on page 1 of the Gloucester Historical Time-Line, was not Thorstein’s, Leif’s, and Thorvald’s brother, as stated, but was the husband of Thorstein’s widow. He established trade with the skraelings as far south as Keelness, which was nevertheless well north of Cape Ann, and he is not known to have explored the coast as far as Virginia.

- Between 1867 and 1920, the top half of Plymouth Rock was enshrined under this Victorian canopy designed by Hammett Billings. In 1920 the famous architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White designed the present-day site with the bottom half of the boulder at sea level, washed by the tide. Read the real story of Plymouth Rock at the History Channel: http://www.history.com/news/the-real-story-behind-plymouth-rock.

- The explorers John and Sebastian Cabot, father and son, were among the famous merchant adventurers from Bristol, England. Both appear in a 1930 group portrait by Ernest Board (“Some Who Have Made Bristol Famous”) along with Martin Pring and Ferdinando Gorges. See P. L. Firstbook, The Voyage of the Matthew: John Cabot and the Discovery of America (1997) and Evan T. Jones, Alwyn Ruddock: John Cabot and the Discovery of America. Institute of Historical Research Volume 81, Issue 212 (May 2008): 224-254 (first published online: 5 APR 2007). Diogo Ribeiro’s map is reproduced on page 22 of Moses Sweetser’s 1882 book, The White Mountains: A Handbook for Travellers (see http://archive.org/details/whitemountainsa01sweegoog). A classic primary source for early voyages is Samuel Purchas’s 1625 Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and lande Travells by Englishmen and others. A convenient collection of primary source accounts from Hakluyt is in Burrage’s 1906 Original narratives of early English and French voyages 1534-1608, reprinted in 1930 as Early English and French voyages, chiefly from Haklyyt, 1534-1608. A classic secondary source is Synge’s 1939. A Book of Discovery: the History of the World’s Exploration, from the earliest times to the finding of the south pole (see http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/23107).

- Jaime O’Leary describes Basque whaling ports in Labrador in the 17th Century (see http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/basque.html). John Brereton’s 1602 account of Bartholomew Gosnold’s voyage of discovery to New England, A brief and true relation of the discovery of the North Virginia, edited by Karle Schlieff, may be read at http://ancientlights.org/gosnold.html. Read The Voyage of Martin Pring, 1603 at www.americanjourneys.org/aj-040/ and Alfred Dennis’s 1903 interpretation of Pring’s first voyage at http://www.archive.org/details/captainmartinpriOOdenniala. Juan de la Cosa’s circa 1500 Mappa Mundi, is described at http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/cosa_cart.html. For Champlain references, please see Chapter 3 of this book.

- Edward Hayes’ account of the Voyage of Sir Humfrey Gilbert, Knight, 1585 is in Henry S. Burrage’s 1908, Early English and French Voyages, Chiefly from Haklyut, 1534-1608: 177-222.

- Jacques Cartier’s 1543 “dauphin’s map” of North America shows Breton fishing posts on the coast of the Gulf of Maine as far as the Kennebec River.

- For early explorers’ maps see Terra Incognita. Early Accounts, the DeBry Collection of “Great and Small Voyages” at http://library.wustl.edu/units/spec/exhibits/terra/index.html. See also the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection (Maps of North American discovery and expansion) at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/. For a summary of Verazzano’s voyage along the North American coast in 1534 see William Hobbs article in Isis 41 (3/4, December 1950): 268-277. Sources for Norumbega include Emerson Baker et al., American beginnings: Exploration, culture, and cartography in the land of Norumbega (1994); Sigmund Diamond, April 1951. Norumbega: New England Xanadu. In The American Neptune Vol. 11: 95–107. An alternative history is offered in H. G. Brack’s 2006 Norumbega Reconsidered: Mawooshen and the Wawenoc Diaspora: The Indigenous Communities of the Central Maine Coast in Protohistory 1535-1620 (Davistown Museum Publication Series Volume 4). Marc Lescarbot’s 1609 map of Acadia is in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University in Providence, RI. Lescarbot was on one of Sieur de Poutrincourt’s voyages of discovery, sponsored by Sieur de Monts (Pierre Dugua du Mons), a French Huguenot, who also sponsored Samuel de Champlain. Marc Lescarbot’s map of New France shows the Locations of the Souriquois (Mi’Kmaq), Etechemins (Eastern Abenaki), and Armouchiquois (Western Abenaki) and some of the places Champlain named, such as Chouacoet (Saco) and Malebarre (Nauset Harbor in Easton, MA). The Norumbega place name appears along the Penobscot (rather than the Kennebec) River. For Jean Alfonse (Allefonsce) and others, see the Hakluyt. The detail of Norombega on the Kennebec is from Gerardus Mercator’s 1569 world map, Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata, which has copies in Paris, Breslau, Basel, and Rotterdam and can be readily viewed online. A source on Norridgewock is J. W. Hanson, History of the Old Towns Norridgewock and Canaan, Starks, Skowhegan, and Bloomfield… (1849) at http://www.archive.org/details/historyofoldtown00hans.

- The idea that Norumbega was on the Charles River in Cambridge or Watertown was promoted by Eben Norton Horsford in 1886 and 1889 in letters to the president of the American Geographical Society (“John Cabot’s Landfall in 1497 and the site of Norumbega” and “The discovery of the ancient city of Norumbega”). Cartographer Andy Woodruff considers this idea and presents Horsford’s and others’ maps at http://andywoodruff.com/blog/norumbega-new-englands-lost-city-of-riches-and-vikings/. An article on Norumbega Park and the Totem Pole appears in a 1910 article by Charles Rockwood, “At the Gateway of Boston Harbor”, in The New England Magazine (42).

- Francesco-Giuseppe Bressani’s 1657 map, Novae Franciae Accurata Delineatio is in the National Archives of Canada. Francesco Bressani (1612-1672), an Italian-born Jesuit priest, requested to be posted to New France as a missionary. He survived being kidnapped, tortured, and traded by Iroquois. His map illustrations and accounts were used to promote investment in missionary work in North America.

- The quote from Columbus’s letter book comes from Christopher Columbus Log Excerpts, 1492 A.D. in The Franciscan Archive: www.franciscan-archive.org. The 1594 engraving of Columbus meeting the Taino is by Theordore de Brys, also the depictions in this chapter of Gosnold meeting the Pennacook and Newport meeting the Powhatan in what would become Jamestown.

- The quote from Verrazano’s account is in H. C. Murphy’s 1916 translation of Verrazano’s Voyage along the North American Coast in 1524.

- See, for example, B. F. DeCosta’s 1890. Ancient Norumbega, or the voyages of Simon Ferdinando and John Walker to the Penobscot River, 1579-1580.

- The quote from Edward Hayes’ account and other relevant excerpts are from George Parker Winship’s Sailors narratives of voyages along the New England coast, 1524-1624 (1905). See also Gillian Cell’s English enterprise in Newfoundland 1577-1660 (1969).

- See the 1906 edition by James Phinney Baxter of Jean Alfonce’s account of Cartier’s voyages: A Memoir of Jacques Cartier: Sieur de Limoilou, His Voyages to the St. Lawrence, a Bibliography and a Facsimile of the Manuscript of 1534. Note that Cartier’s chronicler Jean Alfonce, also spelled Allefonsce, was also known as Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge, and he included the exploits of Cartier’s colleague in exploration, Jean François de sieur de La Roque Roberval. The image of Cartier meeting the Beothuk (the Red Men) is a 1915 copy by James P. Howley of an 1808 painting commissioned by the governor of Newfoundland as a kind of public relations outreach to the remaining Beothuk.

- See Note 21. Also see pages 55-70 in Frank Speck’s Beothuk and Micmac (1922).

- A definitive work is Ingeborg Marshall’s 1998 History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

- Read more about Demasduit and Shanawdithit in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- See The Voyage of Martin Pring, 1603 and Brereton’s account of Gosnold’s discovery, referenced in Note 12.

- The story of Gosnold getting directions from the Abenakis at Savage’s Rock is told in A chronological history of New-England: in the form of annals, being a summary and exact account of the most material transactions and occurrences relating to this country, in the order of time wherein they happened, from the discovery of Capt. Gosnold, in 1602, to the arrival of Governor Belcher, in 1730…by Thomas Prince and Nathan Hale (1826).

- Compare this chalk on bedrock story with the six pebbles story in Chapter 3.

- This quote comes from Brereton’s account.

- The quote from Gosnold’s letter to his father is in “Master Bartholomew Gosnold’s Letter to his Father, touching his first voyage to Virginia, 1602,” Old South Leaflets 5 (120) and may be read at Virtual Jamestown: http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/vcdh/jamestown. Gosnold’s emphasis on the healthfulness of the place may be a reflection of the Bubonic plague and typhoid epidemics in Europe at the time.

- The practice of kidnapping Indians to be displayed in Europe and returned as translators and guides is described in more detail in Chapter 14. See George Prince’s 1857 account, “The voyage of Capt. Geo. Weymouth to the coast of Maine in 1605” in Maine Historical Society Collections VI: 291-306. See also Henry Burrage’s 1887 Rosier’s relation of Weymouth’s voyage to the coast of Maine, 1605, published by the Gorges Society. This practice of abduction was established early. In 1534, for example, Cartier took Donnacona (chieftain at what would become Quebec City) and several others to France and returned with those who survived on his second voyage to North America. Donnacona, although treated well, died soon after being taken to France a second time.

- Richard Hakluyt’s account is in Samuel Purchas. Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes (1625). The Hakluyt detail is from a larger engraving entitled “England’s Famous Discoverers” in the National Maritime Museum, London.Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616) was a famous writer of exaggerated stories of travel and adventure. These stories were used as propaganda for English exploration and empire building during the Elizabethan era.

- The quote is from James Rosier’ account, who was with Weymouth on the Archangel. See A True Relation of Captaine George Weymouth his Voyage. Made this Present Yeere 1605, pages 125-127 in the 1843 reprint by the Massachusetts Historical Society. The quote also appears in Burrage’s Early English and French voyages chiefly from Hakluyt 1534-1608 (1930).

- See Rosier’s account in Note 32.

- For the story of George Popham’s colony at Sagadahoc, see John Wingate Thornton’s August 29, 1862, speech at Fort Popham: Colonial Schemes of Popham and Gorges (Maine Historical Society). See also James Davies’ account. He was the navigator of Raleigh Gilbert’s vessel in Popham’s fleet. His Relation of a voyage to Sagadahoc, 1607-1608 was reprinted by the Hakluyt Society in 1849 and the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1880. The roles of Popham’s native guides, including Skidwares and Nahanada (who figures later as Captain John Smith’s informant at Pemaquid known as Dohannida) are taken up again in this chapter.

- This quote about Popham at Pemaquid is from A History of Pemaquid with sketches of Monhegan, Popham, Castine by Arlita Parker (1925).

- Messamoet and Membertou are in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. See, for example, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/membertou_1E.html. The quote from Henry Hudson’s account is taken from the Hakluyt and also appears in the Burrage.

- Smith’s views on Native Americans, including their proposed use as forced labor and suppression during the founding of Jamestown, are abundantly evident in his 1608 account, A True Relation of Such Occurrences and Accidents of Note as Hath Hapned in Virginia Since the First Planting of that Colony, which is now resident in the South part thereof, till the last returne from thence. Written by Captaine Smith one of the said Collony, to a worshipfull friend of his in England (1608). See http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/J1007.html. See also William Strachey’s 1612 account, The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania, published by the Hakluyt Society (Volume 133) in 1953.

- See Smith’s Map of New England [in 1605], published in 1614, at http://www.plimoth.org/education/teachers/smithMap.pdf, and compare this with his map of New England published ten years later in 1624 in Volume II of The generall historie of Virginia, New England & the Summer Isles: together with The true travels, adventures and observations, and A sea grammar.

- Smith credits earlier discoverers of New England in his 1608 account, cited in Note 37. See also his 1616 account, A Description of New England: Or the observations, and discoueries of Captain John Smith (Admirall of the Country) in the north or America, in the year of our Lord 1614: With the success of sixe ships, that went the next yeare 1615; and the accidents befell him among the French men of warre: With the proofe of the present benefit this country affords: Whither this present yeare, 1616, eight voluntary ships are gone to make further tryall. This was published in 1837 in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd series. 6: 103-140.

- This quote is from Smith’s Description of New England, cited in Note 39.

- Smith has little to say about Dohannida (Nahanada), except that befriending the chieftain gave him credit among the natives and some power over them. Smith’s summer in Maine with Dohannida is described in William Baker’s A maritime history of Bath, Maine and the Kennebec River region. (Marine Research Society of Bath, 1973). It seems likely that during that time Smith learned from Dohannida the Algonquian place names for coastal villages on the Gulf of Maine, including Cape Ann, that appeared on his 1616 and 1624 maps of New England.

- See Note 38. Smith’s 1624 map also includes the first colonies established by the Pilgrims. The most complete map appears in his 1630 account, The True Travels, Adventures and Observations of Captain John Smith in Europe, Asia, Africa and America, published by The Winthrop Society. Smith died in 1631.

- The Dry Salvages is the third poem of T. S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets”, first published in February 1941 in the New English Weekly.