The Maritime or Coastal Archaics of the Northeast made their living by hunting marine mammals, fishing, and shellfish gathering. They depended on the sea and lived in rocks and temporary camps along the shore over a 6,500-year period, the longest span of occupation here. The great majority of artifacts from archaeological sites here are from the Archaic Period.

“Red Paint People”

The earliest Archaics in the Northeast were the so-called Red Paint People, or people of the Moorehead Tradition or Moorehead Phase (after Warren K. Moorehead, the archaeologist who described their burial traditions in 1922, following their discovery by Charles Willoughby in 1892). Today referred to as Marine Archaics, these people lived during the Early Archaic period (between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago) and got their name from their extensive use of red ochre in every aspect of their culture. They used red ochre in their elaborate burials, for example, discovered in coves and islands on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Gulf of Maine. The red ochre—hydrated iron oxide (FeH3O) or hematite (Fe2O3) obtained from clay—was powdered and mixed with oil from fish or marine mammals and used to line burial pits, cover the bones, and paint grave goods. In Maine their distinctive burials are referred to as the Maine Cemetery Complex.[1] Out of respect for Indigenous Peoples today, whose remote ancestors’ graves were over centuries looted for museum exhibits and trophies for private collectors, I have not included photos of ochre-painted human remains.

Burials were located on sandy ridges or terraces above the high tide line or on riverbanks—for example, on the St. Lawrence River, the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers in Maine, and the Merrimack in New Hampshire. Bodies were buried in the ground and later ceremonially disinterred. Grave goods were put into the burial pit, which was then coated with red ochre. Then the defleshed skeletal remains of the deceased, painted red, were reinterred in a flexed (fetal) position. More grave goods were placed on top of the bones—choice weapons, ornaments, and tools—and the whole assemblage was covered all over again with red ochre. Later, during the Middle Archaic period, their burial practices changed. Layers of charcoal and the presence of calcined (burned) bone and fire-cracked stone implements in burial pits indicate that bodies were cremated, including those of small mammals or birds placed on top of the remains as grave goods.[2] Cremation burials have also been found on islands in Ipswich Bay and Essex Bay.[3]

Archaic Period Technologies

The Marine Archaics occupied the islands and river mouths of coastal northern New England, the Canadian Maritimes, and Newfoundland, where they hunted marine mammals and birds and fished from year-round seaside base camps. Their tool assemblages show they were highly specialized in their adaptation to the seacoast and marine resources. Their material culture included fishing plummets, net weights, flaked stone knives, ivory harpoons and fish hooks, bannerstones (symmetrical stones with holes bored through them to add weight to spear throwers), animal effigies (figures carved in stone), and long swords or rods of ground slate.[4] They had ocean-going canoes and were deep-sea hunters of swordfish, grampus (a North Atlantic porpoise), walrus, and whales in addition to land-based seals and caribou. The “Red Paint People” were not, and are not, “mysterious” as popular media suggest. Their mystification began in the late 1860s with early archaeologists, and it has taken more than a hundred years to correct public misperception—if, indeed, that is the case.[5] Science and Romance often rub noses.

Maritime Archaic aquatic hunting gear from Riverview, Gloucester (Courtesy Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, M.E. Lepionka photo)

In Massachusetts Early Archaic sites with red ochre and characteristic mortuary practices and tool types include Morrill Point on the Merrimack River in Salisbury and Wapanucket on Lake Assawompsett in Middleborough.[7] In the 1920s, a short-channeled gouge that appears to have been painted with red ochre was excavated from the grounds of the Rockport Golf Club. Artifacts from the Middle and Late Archaic periods (8,000 to 3,500 years ago) are more abundant in Cape Ann collections, including those of Marshall Saville and N. Carleton Phillips.[8]

Replica of an ochred short-channeled gouge from the grounds of the Rockport Golf Club (Courtesy Sandy Bay Historical Society, Rockport)

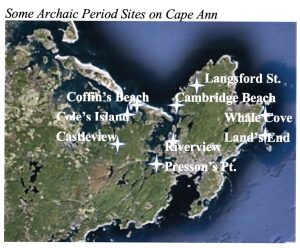

Some Archaic Period Sites on Cape Ann[9]

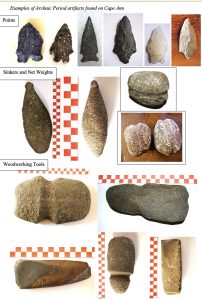

Examples of Archaic Period artifacts found on Cape Ann[10]

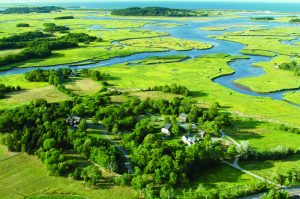

Middle and Late Archaic remains on Cape Ann show how people adapted to life on the drowned river mouths we call estuaries and on the salt marshes, sand dunes, and barrier beaches that began to form only around 5,000 years ago.[11] People of the Middle Archaic were the first to exploit the resources of Cape Ann’s rich estuarine biomes. Their discovery of shellfish (especially oysters, mussels, and clams) as a food resource transformed their way of life, because shellfish provide year-round easy access to localized high-quality animal protein. The oldest layers of shell middens (piles of refuse from the consumption of shellfish) dotting our estuaries (especially at the mouths of the Annisquam, Essex, Ipswich, and Rowley rivers ) contain oyster and mussel shells dating to that time. Wheeler’s Point on the Annisquam River in Gloucester, Clam House Landing on the Essex River, and the seaward side of Hog (Choate) Island in Essex Bay, for example, are land forms created in part by the compacted deposition of shell refuse over thousands of years of occupation beginning in the Late Archaic Period. Hickory tress have grown up through the midden at Hog Island and cedar trees through the one at Clam House Landing, bringing up shells among their roots. [12]

Essex Bay Estuary viewed from the Allyn Cox Reservation and shell midden at Clam House Landing (Courtesy Essex County Greenbelt Association)

The Cape Ann Archaics did not specialize in hunting swordfish, as some others did, but were deep-sea fishers, evidenced by the bones of anglerfish in one of their sites. We also find bones of extinct or near extinct species of animals and birds, such as the flightless great auk, passenger pigeons, the sea mink—a kind of saltwater adapted weasel, Eastern grey wolf dogs, and Eastern elk, later replaced by the bones of whitetail (Virginia) deer.[13] Bones of the great auk, sea mink, other extinct species, and deep-sea Atlantic anglerfish, also called Football Fish, have been found in Middle Archaic sites on Cape Ann and vicinity. Plummets (sinkers) and grooved net weights have been found in caches on Cape Ann’s northeastern beaches and headlands, for example at Gap Head, Flat Point, Lands End, and Penzance Road in Rockport, opposite off-shore islands. Those islands historically had dense rookeries of great auk and other sea birds, and bird netting undoubtedly occurred there along with net fishing in the channels and intertidal zones. Tools for processing fish and meat are common in Archaic sites, such as semi-lunar knives (also known as ulus or mezzalunas), often carved from slate and used for defleshing bone or scaling fish.

Species exploited by Essex County Coastal Archaics:

Sea Mink (Creative Commons) Great Auk (John Gould, Public Domain)

Axes, Atlatls, and Dugouts

In addition to fishing gear the Cape Ann Archaics had woodworking tools, especially polished gouges, celts, and axes. Woodworking tools had a concentration in Pigeon Cove and Andrews Woods, for example, which at that time had a dense forest of spruce, fir, rock maple, sycamore, hickory, aspen, black birch, and basswood.[14] Gouges were used to turn trees into dugout canoes. The Archaics also invented spear-throwers, or atlatls, and added bannerstones to them–weights carved from soapstone. The atlatl is a simple machine that uses leverage with an artificial extension of the arm, which increases rotational force or angular velocity. Using an atlatl, a person can throw a spear or dart farther, faster, more accurately, and more powerfully than by hand alone.[15] The atlatl was ideal for spearing deer feeding on salt marsh grasses from a distance. The spear-thrower was a technological breakthrough for the people of the Middle Archaic, much as the Clovis point had been a technological breakthrough for the Paleoindians. An illustration of atlatl throwing by Donald Monkman, from Pettipas 1996[16] appears in a previous section.

Some atlatl bannerstones (weights) in local collections (M.E. Lepionka photos)

People of the Archaic Period relied more on local stone for their tools. They prized easily carved and dense local soapstone (steatite, talc), for example, and found many uses for it other than sinkers and atlatl weights. They used soapstone to carve dishes, bowls and other vessels, and figurines. The people quarried or traded for soapstone from along the banks of the Merrimack River and sites in Andover, Newburyport, and Georgetown, for example on the Skug River and in the Harold Parker State Forest. A rich belt of talc extends all along the coastal plain of the Appalachian Mountains, and the distribution of soapstone vessels, figurines, and gorgets is around this belt.[17] Also, locally available slate–metamorphosed mud–fractures easily and was easily worked and reworked into both sharp-edged implements and smooth-edged ornaments. Rounded slate panels, for example, were perforated, strung, and worn as gorgets across the throat or chest as adornment or micro armor. Regional sources of slate included ancient quarries in Quincy and Milton, and people also obtained slate from quarries in Vermont and Maine.[18]

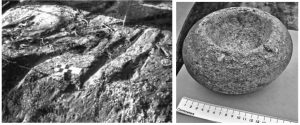

Indigenous soapstone quarry on the Skug River and a soapstone mortar[19]

Quarried slate preforms and slate gorget[20]

Quarried slate preforms and slate gorget[20]

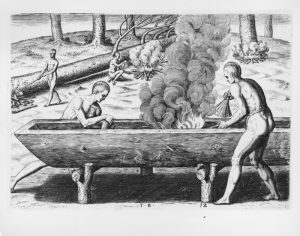

Here is Champlain’s 1606 description of the method of making dugout canoes:

The canoes of those who live there are made of a single piece, and are very liable to turn over if one is not skilful in managing them. We had not before seen any of this kind. They are made in the following manner. After cutting down, at a cost of much labor and time, the largest and tallest tree they can find, by means of stone hatchets (for they have no others except some few which they received from the Savages on the coasts in exchange for furs), they remove the bark, and round off the tree except on one side, where they apply fire gradually along its entire length; and sometimes they put red-hot pebble-stones on top. When the fire is too fierce, they extinguish it with a little water, not entirely, but so that the edge of the boat may not be burnt. It being hollowed out as much as they wish, they scrape it all over with stones….

John White illustration of making a dugout canoe Archaic Period dugout replica

Champlain describes canoes in Chapter 2 of Volume 1 (1603) and in Chapter 7 of Volume 2 (July 16,1604), in Voyages of Samuel de Champlain of Brouage, The deBry etching of men making dugouts is from the latter. Roger Williams (1643, p. 109) reports that a man working alone typically could make a dugout canoe in 12 days. Half-channel gouges were found in Pigeon Cove, Rockport, and there are many other examples from Cape Ann, Essex, and Ipswich. They are the type of gouge Indigenous people would have used with fire to hollow out logs and tree knots for dugout canoes, mortars, and bowls.

Dugouts were not as common north of Massachusetts Bay, and none have been discovered yet in the estuaries here. However, colonists were known to reserve large oak trees for use as dugouts to serve as foundations for hayricks to transport salt marsh hay (Plane 1991, p. 12). Howard Chapelle also describes colonial adaptations of Native boats in his chapter, Colonial and Early American Boats, in American Small Sailing Craft: Their Design, Development, and Construction (1951).

Stone tools used to gouge out dugout canoes have been found on Cape Ann. Men weakened selected trees using controlled fire all around the base before felling the tree. Fire was more effective than stone as a tool for processing trees, and remains of base-burned trees taken for dugouts may still be found in old growth forests in New England. The remains of dugout canoes have been found in ponds and river bottoms in Massachusetts, for example in Lakeville, Taunton, Weymouth, and North Reading, but to date none have been discovered on Cape Ann. Written records (e.g., Gage 1837 History of Rowley) suggest that colonists in Ipswich, Rowley, and Essex repurposed Native dugouts and made their own for use as salt marsh hayricks.

Essex County as a Stone Age Paradise

With all its rocks, Cape Ann must have seemed a paradise for Stone Age people. They used the granite and basalt for toolmaking and pried out the crystals and minerals for ornaments, trade goods, and shamans’ magic. Both Late Archaic and Woodland Period people mined seams of quartz and pried out nuggets from the granite pegmatites, syenites, felsites, gabbros, and basalts that make up Essex County. Rocks, minerals, and ores recovered in archaeological sites around here include citrine quartz, fayalite or blue quartz, smoky quartz, garnet, opal, zircon, fluorite, danalite, olivine, amethyst, halite, galena, calcite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, magnetite, kaolinite, hematite, mica, and others.[21]

The rocks in Folly Cove may constitute a felsite debris field–the remains of a manufacturing site where indigenous people worked stone cores, flakes, points, and blades, leaving debitage long churned and buried in the tides. Caches of stone preforms (blocks of stone people collected and shaped for further reduction into tools elsewhere at a later time) have been found along Langsford St., suggesting that Lane’s Cove was another indigenous quarrying or manufacturing site on Cape Ann. Gabbro outcrops in Lane’s Cove show signs of having been mined for crystals of olivine.

Folly Cove felsite manufactory and Lane’s Cove source of olivine (M.E. Lepionka photos)

People made stone tools in stages: quarrying or mining the rock—hammering stone wedges to widen natural cracks, and then using hammer and chisel to shape the stone to carry away or store for future reduction. At a manufacturing site they then applied percussion flaking or pressure flaking to the preform to reduce it to its intended form. The piece was finished and put into use and subsequently refinished, until repurposed for another use and ultimately discarded as useless. Authentic artifacts are identified in part by their use wear.[22]

Granite preform from Essex Falls, intended for an axe[23]

Cape Ann’s granites intruded on Cambrian bedrock during the Ordovician and Silurian geologic eras, beginning around 450 million years ago. Granite is intrusive igneous rock, classified by its density and mineral content and the size of its mineral grains. Intrusive igneous rocks with very large grains of feldspar, quartz, mica, biotite, or other minerals are called pegmatites, and Cape Ann is famous for them. Fine-grained or micrographic granite was the opposite, prized in historical times as building stone, which led to the development of our historic granite quarrying industry, such as the gray granite quarried in the 19th century at Halibut Point.[24] Granites can appear to be gray, red, orange, pink, yellow, or white depending on mineral composition and are also classified by the amount of quartz they contain. Granite at Stage Fort Park and the western tip of Rocky Neck contains more than 25 percent quartz, for example, and is classified as pegmatite. In contrast, micrographic granite at the top of the harbor and the eastern tip of Rocky Neck contains less than 5 percent quartz.[25]

Dikes (intrusive bands of igneous rock) of different age and content cut through the granite. They mark fault lines in the crust here and are so numerous they are referred to as a swarm. Porphyritic basalt and felsite dikes are dense, dark volcanic seams with large-grained crystals of minerals. They occur on Dolliver’s Neck, for example, at Cathedral Rocks in Pigeon Cove, and at the head of Folly Cove. Ten Pound Island has diabase dikes (fine-textured feldspar), and a rhyolite dike (extrusive light-colored fine-grained rock) runs into Wonson Cove. Geologists refer to our complex and diverse collection of rocks as the Cape Ann Plutonic Suite.[26] Indigenous people here pried crystals from pegmatites and quarried basalt, prized for making celts (polished stone adzes), and rhyolite dikes for projectile points, most famously from an Indigenous rhyolite mine in Marblehead.

Pegmatite containing blue quartz and a basalt dike on Cape Ann[27]

Examples of artifacts made in basalt and a core of Marblehead Rhyolite[28]

Cape Ann’s rocks are different from other localities in Massachusetts because Cape Ann was not part of the formation of the North American continent in the deep past. It was an island off Avalonia that bumped into and got stuck onto the continent’s edge as a result of a more recent transformation of the Atlantic Ocean involving volcanic fault lines. Cape Ann has many such fault lines, including major ones that run through Gloucester’s Western and Inner harbors, and is seismically active.[29] On November 18, 1755, an “Intensity VIII” earthquake heavily damaged Cape Ann, toppled chimneys and steeples in Boston, and changed the flow of groundwater in several communities, causing local droughts. The 1755 earthquake was felt as far away as Nova Scotia, New York, Maryland, and a ship at sea 320 km east of Cape Ann. The epicenter was just off Gloucester Harbor.[30]

Woodcut Showing Effects of the Cape Ann Earthquake of 1755 on Boston

Cape Ann’s rocks are difficult to work, requiring a hammer and peck method, like marble, as opposed to easily flaked chert, flint, and obsidian, which do not occur here. People of the Archaic Period on Cape Ann were expert stoneworkers with technical knowledge of lithics and landscapes that few people possess today. In the Late Archaic Period (5,000 – 3,500 years ago) they made full-grooved granite axes, basalt celts, and small projectile points in local stone such as felsite and rhyolite for use with atlatl darts or bows and arrows. They also made pots from local marine clays in which they cooked fish and shellfish. The first use of fish weirs–fences constructed across river outlets to trap migratory fish–date to this period. Changes in projectile point and pottery styles, and the introduction of the bow and arrow mark the end of the period or a transition to the next archaeological period, called the Woodland period.

Late, Terminal, or Transitional Archaics?

The difference between “Terminal Archaic” and “Transitional Archaic” refers to the debate as to whether Late Archaic people developed Woodland Period technologies on their own in situ (Transitional Archaic) or whether Woodland Period technologies were introduced by new populations migrating into New England (Terminal Archaic). As with most such debates, both scenarios likely were involved. The Archaics were making pottery, trapping migratory fish, and turning trees into dugout canoes prior to the arrival of the so-called Eastern Woodland Indians, for example, while the Woodland people were decorating their pottery in distinctive styles and for different uses, making fish nets, and constructing birch-bark canoes. Many archaeological sites have a combination of these technologies suggesting a period of cultural reintegration after Woodland people migrated into the area around 3,500 years ago and met the people who were already living here.

The bow and arrow seems to have been a technological breakthrough introduced by new migrants into the region, marking the beginning of the Woodland Period, providing even greater range and accuracy than the atlatl. Its use, along with increased shellfish consumption, contributed to increases in population size and stability.[31] Changes in projectile point and pottery styles mark a transition between the Archaic and Woodland periods in Indigenous history.

Diagnostic Changes in Projectile Points and Tool Types[32]

The Coffin Stream Assemblage and Shattuck Farm

Important “Terminal” or “Transitional” Archaic finds relevant to the indigenous history of Cape Ann include a collection of artifacts from the Coffin Street site in West Newbury and the Shattuck Farm site in Andover. In West Newbury, Late Archaic and Early Woodland people occupied a site on the Artichoke River near Indian Hill continuously for more than 3,000 years. Evidence for this comes from a famous collection of artifacts known as the Coffin Stream Assemblage, gathered by several generations of one family over an 80-year period as they worked their market garden in a plot along a tributary of the Merrimack River at the end of Coffin Street in West Newbury where they lived.[33]

Artifacts from the Coffin Stream Assemblage

The Shattuck Farm site in Andover and the nearby area around Lake Cochichewick show continuous occupation over a 5,000-year time span from the Late Archaic to the Contact Period. The Shattuck site, now completely destroyed for industrial development, was a series of alluvial terraces on the Merrimack River near a waterfall and wetlands, an ideal location for fishing, hunting, gathering, and for river transportation. The area would have been productive in nearly every season of the year.[34]

The Shattuck Farm Site: A Late Archaic-Early Woodland Encampment[35]

The different styles and sizes of dwellings at the Shattuck Farm site suggest that diverse bands of people came together seasonally. They hunted and fished together and no doubt reaffirmed their kinship ties, chose marriage partners, shared information and goods, and performed community ceremonies. Bands were staying together for longer periods in stable resource areas that allowed the development of three-season mixed economies. Animals and plants were more diverse and plentiful because of climate change, herds stayed within a territory rather than migrating long distances, and fish and shellfish became more important as subsistence resources. Early Woodland people also lived like this. While Archaic people abruptly disappear at some sites, other sites contain both Late Archaic and Early Woodland tool types. This diversity and mixing of technologies of different peoples suggests cultural contact and acculturation. But where were the Woodland people coming from, why, and how were they different?

Return to What people lived in Essex County and when?

Notes and References

[1] Warren K. Moorehead’s classic works describing the so-called Red Paint People include The Stone Age in North America (1910), The Red-Paint People of Maine, in American Anthropologist 15 (1) (1913), and A Report on the Archaeology of Maine (1922). His work with Benjamin Smith for the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology resulted in the 1931 Merrimack Archaeological Survey. See Benjamin Smith (1948), An analysis of the Maine Cemetery Complex, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 9, and Nicholas Smith (1955), The Survival of the Red Paint Complex in Maine, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 17.

[2] Details on Red Paint burials may be found in M. Renouf and Trevor Bell, Across the tickle: The Gould Site, Port au Choix-3 and the Maritime Archaic mortuary landscape (2011), in The cultural landscapes of Port au Choix: Precontact Hunter-Gatherers of Northwestern Newfoundland, and in Brian Robinson, Archaic Period burial patterns in northeastern North America, in The Review of Archaeology 17 (1) (1996). For a perspective on changing patterns of inhumation and cremation, see Dena Dincauze’s 1968 paper, Cremation cemeteries in eastern Massachusetts, in Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 59 (1).

[3] Sites with burned bones on islands in the Essex and Ipswich bays, reported as evidence of cannibalism among early inhabitants, such as on Perkins Island (for example, in Waters 1905 Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony), were actually the remains of cremation burials, suggesting that Early Archaics lived as least as far south as Cape Ann.

[4] Archaic Period artifact identifications are based on Jeff Boudreau’s A New England Typology of Native American Projectile Points (2008) and William Fowler’s A Handbook of Indian Artifacts from Southern New England (1991).

[5] The romanticizing and mystification of the “red paint people” has been perpetuated in recent times by Walter Smith in the Abbe Museum’s The Lost Red Paint People of Maine (1930) and more recently in T. W. Timrick and William Goetzmann’s Mystery of the Red Paint People: The discovery of a prehistoric North American sea culture (1987), an archaeological docudrama by Bullfrog Films that also aired on NOVA the same year.

[7] The Morrill site is described in Brian Robinson’s 1996 paper, A Reginal analysis of the Moorehead Burial Traditions: 8500-3700 B.P. in Archaeology of Eastern North America 24: 95-148. See also his 1985 paper, The Nelson Island and Seabrook Marsh Sites: Late Archaic, Marine-Oriented People on the Central New England Coast, Occasional Publications in Northeastern Anthropology 9: 1-104. For Wapanucket, see Maurice Robbins, 1959, Wapanucket: An archaic village in Middleboro Massachusetts (Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Middleborough MA).

[8] My articles referring to the maritime archaics in Essex County include the following:

2013 Unpublished papers on Cape Ann Prehistory, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (2): 45-92.

2017a Algonquian Shellfish Industries on Cape Ann, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (1): 28-40.

2017b Speck in Riverview, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (2): 60-70.

2018a Maritime Archaics in Essex Bay: The Saville and Ellis Collections, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 79 (1): 65-74.

2018b Ancient Pottery from Cape Ann, Essex, and Ipswich, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 79 (2): 65-74.

[9] These are Middle Archaic and Late Archaic sites on Cape Ann. Clark’s Pond on Great Neck in Ipswich was an Archaic Period site excavated by Ripley Bullen in 1948 and 1949. See Bullen’s article, Excavations in Northeastern Massachusetts: The Clark’s Pond Shell Heap, in Papers of the Robert S. Peabody Foundation, I (1949). The artifacts Bullen recovered are very similar to those found on Cape Ann and the islands of Essex Bay in the collections of Marshall Saville, S. Foster Damon, Frank Speck, Frederick Johnson, N. Carleton Phillips, Tom Ellis, and others at sites including the ones shown on the map. See also Mark Greenly’s 2003-2004 reappreciation of Bullen’s site: The Clark’s Pond Shell Heap Site in Ipswich, Massachusetts: Revisiting Great Neck and Plum Island Sound, in New Hampshire Archaeologist 43-44 (1).

[10] These Archaic Period artifacts are from the collections of Marshall Saville at the Sandy Bay Historical Society, N. Carleton Phillips at the Cape Ann Museum, Tom Ellis, and the Ipswich Museum.

[11] For information on the Essex County Great Marsh, see https://www.mass.gov/service-details/great-marsh-acec.

[12] Cape Ann and other coastal New England settlement areas are dated mainly by shell midden analysis in terms of the composition of the refuse piles and diagnostic indicators such as mollusks’ biological adaptations to climate change; the statistical analysis, age, and DNA of discarded animal and bird bones; the mechanical and chemical analysis of potsherds, tool fragments, caches, and fire pits in or near the middens; and the study of proximate human burials. A classic general source is Bruce Trigger’s Native Shell Mounds of North America (1986). See also Jordan Kerber’s 1985 article, Digging for clams: Shell midden analysis in New England (North American Archaeologist 6 (2) and Dena Dincauze’s definitive synthesis (1997), Deconstructing Shell Middens in New England (The Review of Archaeology 17 (1)). Local excavations of shell heaps began after the Civil War with F. W. Putnam’s 1867 and 1869 works, On Indian remains in Essex County (Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Vol. 5) and On shellheaps in Essex County (Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol. 1). Putnam went on to become the curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University from 1874 to 1909. More contemporary work began in the 1940s with Ripley Bullen’s excavations of middens on Great Neck, Ipswich. See Bullen’s 1949 Excavations in Northeastern Massachusetts: The Clark’s Pond Shell Heap (Papers of the Robert S. Peabody Foundation, I) and, with J. F. Burtt, his 1947 The Neck Creek Shell Heap, Ipswich, in Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 9 (1). In 2003-2004 a reanalysis of Bullen’s sites was done by Mark Greenly in The Clark’s Pond Shell Heap Site in Ipswich, Massachusetts: Revisiting Great Neck and Plum Island Sound (New Hampshire Archaeologist 43-44 (1)). Other famous shell middens in the annals of archaeology are Damariscotta on the Maine Coast (Sanger and Sanger 1986), the Wheeler’s Site on the Merrimack River (Barber 1982), and others.

[13] The list of extinct species in the Holocene include mammals and birds that were hunted to near extinction by Maritime Archaics and Early Woodland people on the Atlantic coast prior to 1400 that were finished off by Europeans. In addition to the sea mink and great auk, they include the Labrador duck, Eastern cougar, Eastern elk, heath hen, and passenger pigeon.

[14] For sources on old growth forests in Essex County, see my article, “Very Fine Cypresses” (quoting Samuel de Champlain) at https://enduringgloucester.com/2018/05/24/very-fine-cypresses/.

[15] Two feet (0.61 meters) is an optimal length for an atlatl, which can be as simple as a stick with a small fork at one end. The dart or spear is 3 to 6 feet in length, notched to rest firmly against the atlatl’s fork. There were several styles. For instructions for making and using an atlatl and understanding the math, see Janis Cotcher, Atlatl Lessons for Grades 4-12, Centrale des Maths, University of Regina, at: http://centraledesmaths.uregina.ca/rr/database/rr.09.07/cotcher/atlatl/index.html.

[16] Pettipas, Leo, 1996, Aboriginal Migrations – A History of Movements in Southern Manitoba, Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature.

[17] Talc was mined in Newburyport, for example, which is on the band of talc on Appalachian coastal plain (Mindat.org).

[18] See Ken Sassaman, A Southeastern Perspective on Soapstone Vessel Technology in the Northeast. In Levine et al., The Archaeological Northeast (1999), and Suzanne Wall, Aboriginal soapstone workshops at the Skug River II site, Essex County, MA. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 64 (2) (2003). Jasper and soapstone are interesting examples of the influence of source stone for lithic production on people’s movements and associations. See, for example, Richard Boisvert, The Mount Jasper Lithic Source, Berlin, New Hampshire. Archaeology of Eastern North America 20 (1992), and Barbara Luedtke, The Pennsylvania connection: Jasper at Massachusetts sites. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 48 (2) (1987). For a broader perspective see Suzanne Wall’s article with G. N. Eby and Eugene Winter, Geoarchaeological traverse: soapstone, clay and bog iron in Andover, Middleton, Danvers and Saugus, MA, in L. Hanson (ed.) Guidebook to Field Trips from Boston, MA to Saco Bay, ME. (2004).

[19] Wall, Suzanne, 2003, Aboriginal soapstone workshops at the Skug River II site, Essex County, MA, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 64 (2): 30-36. The soapstone mortar is in the Phillips Collection at the Cape Ann Museum.

[20] The gorget, probably worn as a pendant, is Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.

[21] My information on rocks and minerals of Cape Ann also comes from W. H. Dennen’s Rocks of Cape Ann (2001) and Peter Gleba’s Massachusetts Fossil and Mineral Localities (1978), in addition to the Shaler and the Sears; see also James Skehan’s Roadside Geology of Massachusetts (2001) and the Bedrock Geologic Map of the Gloucester and Rockport Quadrangles, Essex County, Massachusetts by W. H. Dennen (1992): http://www.geo.umass.edu/stategeologist/Products/Bedrock_Geology/Gloucester_Rockport/gloucester_rockport.pdf

The best places to look for the minerals mentioned in this chapter are at granite quarries and motions (prospect pits); along Rte. 128 road cuts, especially in the Cherry Hill area; and Briar Neck, Bay View, Davis Neck, Lanesville, Andrews Point, Halibut Point, and Eastern Point.

[22] Examples of local and regional felsite, rhyolite, and quartz projectile points (along with points in imported stone from adjacent regions) may be seen in Jeff Boudreau’s A New England Typology of Native American Projectile Points (2008). A good example of Native American mining of rhyolite for tool production is provided in Richard Boisvert’s article, Mount Jasper Lithic Source in Berlin, New Hampshire, Archaeology Eastern North America 20: 151-166 (1992), also at http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr/documents/aena92mtjasper.pdf. The practice of stone knapping has informed archaeologists about manufacturing techniques, criteria for selecting stone, and other questions of academic interest. However, stone knapping is also a commercial enterprise for craftspeople able to replicate and sell lithic tools without necessarily having training or interest in archaeology. Fabricated stone tools are sold to schools and museums through science supply houses for educational purposes and exhibits, but some are also sold inappropriately online or by antique dealers as authentic Native American artifacts. As with all antiques, the proven provenience and provenance of a piece is essential to know before overpaying for a replica or forgery. For a perspective on relations between stone knappers and archaeologists, see John Whitakker’s 2013 book, American flintknappers: Stone Age art in the age of computers.

[23] From the Eugene Winter Essex Falls Collection at the Peabody Institute of Archaeology, Phillips Academy, Andover MA.

[24] See Charles H. Warren and Hugh E. McKinstry, The Granites and Pegmatites of Cape Ann, Massachusetts, Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 59 (1924). Native Americans mined mica, quartz, feldspar, and kaolin from pegmatites, which were trading assets and sources of wealth. For a perspective on the continuing value of mining minerals from pegmatites, see Granitic Pegmatites: Storehouses of Industrial Minerals, by Alexander S. Glover, William Z. Rogers and James E. Barton in Elements (2012): 269-273: also at http://academics.concord.edu/sckuehn/Geo375/Pegmatites/3glover_Industrial_Minerals.pdf. Barbara Erkilla’s Hammers on Stone (1980) and Paul St. Germain’s Cape Ann Granite (2015) are good sources for the history of granite quarrying on Cape Ann.

[25] For data on quartz content in Cape Ann granite and other data, see the report of the Office of the Massahusetts State Geologist (University of Massachusetts), at http://www.geo.umass.edu/stategeologist/Products/Bedrock_Geology/Gloucester_Rockport/gloucester_rockport.pdf.

[26] An excellent academic source is John Brady and John Cheney’s curriculum (2000-2001), The Cape Ann Plutonic Suite: A Field Trip for Petrology Classes, available at http://www.science.smith.edu/~jbrady/Papers/BradyCheney_B5b.pdf.

[27] The pegmatite at Andrews Point in Rockport is a John Ratti photo; see http://halibutpointnotes.blogspot.com/2014/10/gems-and-geology.html. The basalt dike photo at Cathedral Rocks in Pigeon Cove is by M.E. Lepionka.

[28] The sitting bear is in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem MA. The pestle and celt are in the Saville Collection of the Sandy Bay Historical Society in Rockport (M. E. Lepionka photos). Photo of a core of Marblehead Rhyolite is courtesy of Christine Lewis.

[29] See D. B. Beers’ 1872 Atlas of Essex County, Massachusetts at http://wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=141, and Andrew Alden’s 2010 Massachusetts Geologic Map at http://geology.about.com/od/maps/ig/stategeomaps/MAgeomap.htm. Cape Ann’s fault lines are explained in The Environmental History and Current Characteristics of Gloucester Harbor by Anthony Wilbur and Farah Courtney (2001), Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management: http://www.mass.gov/czm/glouc_harb_rpt_ch1.pdf,ll and in Review of Depth to Bedrock in Gloucester Inner Harbor (2000), Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management Office, Dredged Material Management Plan Phase 2C Program: http://www.mass.gov/czm/dredgereports/2000/dmmp-00-01.pdf. Cape Ann’s seismicity and the woodcut of the Level VIII earthquake of 1755 are presented in Seismicity of the United States, 1568-1989 by Carl W. Stover and Jerry L. Coffman, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1527 (1993).

[30] The woodcut is from a 1755 Boston newspaper. See the USGS web site on Historic Earthquakes at http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/states/events/1755_11_18.php. The original woodcut is in the Jan Kozak Collection at the National Information Serivce Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

[31] Sources on Middle and Late Archaic people in New England include Dianna L. Doucette, Reflections of the Middle Archaic: A view from Annasnappet Pond, in Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 66 (1) (2005); Dena Dincauze, An archaic sequence for southern New England, in American Antiquity 36 (2) (1971), The late archaic period in southern New England, in Arctic Anthropology 21 (2) (1975), and The Neville Site: 8,000 years at Amoskeag, Manchester, New Hampshire, in Peabody Museum Monograph No. 4 (1975); Brian Robinson and Charles Bolian, A Preliminary Report on the Rocks Road Site (Seabrook Station): Late Archaic to Contact Period occupation in Seabrook, New Hampshire, in The New Hampshire Archaeologist 28 (1)(1987); and Eugene Winter, Additional Information on Late Archaic Caches in Essex County, MA (2007). The Massachusetts Archaeological Society 68 (1)(2007).

[32] This diagram is based on the Boudreau typology published by the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. The first column identifies the archaeological periods. the second column lists charactertic point styles in New England, and the name in italics identifies the one shown in the illustration. The third column notes when certain types of tools first appeared, with the understanding that material culture tends to be cumulative, such that items, once introduced, may carry over from one period to the next. The fourth column identifies the types of stone preferred in each period (or found in greater quantity), again with the understanding that all available lithic materials were employed at any given time. Note, too, that classifications vary regionally and temporally as well as popularly among archaeologists.

[33] An example of a terminal/transitional Archaic site is the Wheeler Site near the mouth of the Merrimack River in Massachusetts. See R. Barber, The Wheeler’s Site: A specialized shellfish processing station on the Merrimack River, Peabody Museum Monograph 7 (1982). For information on the Coffin Stream Assemblage, visit or see the web site of the Davistown Museum in Liberty, Maine: http://www.davistownmuseum.org/infoCoffinStream.html.

Artifacts from the Coffin Stream Assemblage, housed in the Davistown Museum in Liberty, Maine, resemble others found in Essex County, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine.

[34] State archaeologist Thomas Mahlstedt identified and surveyed the Shattuck Farm site in 1981 for the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). Barbara Luedtke wrote about her archaeological research there for the MHC in Camp at the bend in the river: Prehistory at the Shattuck Farm site (Occasional publications in archaeology and history No. 1). See also the MHC Guide to Prehistoric Site Files and Artifact Classification System at http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpub/pubidx.htm.

[35] This illustration, courtesy of the Peabody Institute of Archaeology at Phillips Academy in Andover MA, is based on an archaeological reconstruction of the habitation pattern, structures, and features of the Terminal Archaic-Early Woodland encampment at the Shattuck Farm site in Andover.