The mastodon hunters

It appears that Paleoindians first arrived in the Northeast with their Clovis tool kits around 15,000 or 16,000 years ago from the north and west by following the migrations of Late Pleistocene herd mammals, such as mastodons and steppe bison, across the Canadian shield into the Great Plains.[1] Other megafauna of the Pleistocene tundra included mammoths, giant beavers, giant armadillos, wooly rhinos, musk oxen, aurochs (ancestors of cattle), saber-tooth cats, giant ground sloths, camels, horses, dire wolves, and the ancestors of reindeer, caribou, wapiti (elk), and other kinds of deer.[2] Paleoindians also followed the migrations of marine mammals (especially seals and walruses) up and down newly exposed shorelines, as well as migrating cervids (kinds of deer) moving down the margins of glacial lakes and outflow plains to the sea. For example, north-south migration routes of the ancestors of caribou (caribou is an Algonquian word) followed the melt-lines of the receding ice sheet and the glacial lakes left in its wake. Paleoindians with Clovis tools also traveled to the mid-Atlantic up the coast from the southeast and shores of the Gulf of Mexico.[3]

Artist representation of Paleoindian mastodon hunters[4] and mastodon teeth from sea bed off Plum Island

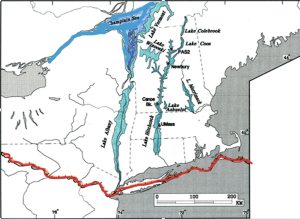

Glacial retreat and glacial lakes as the last ice age was ending[5]

Migration into New England

The uneven retreat of the glacier created new environments swollen with fresh water from the icemelt. Large strings of lakes formed in the river valleys. Paleoindians followed caribou down the Merrimack Valley and Plum Island to choke points on ancient New England shorelines. As they traveled the north-south migration routes, they carried their tools with them wherever they went and visited distant quarries to replenish their tool kits using high quality stone: Ramah chert in Newfoundland; Munsungun chert in Maine, “jasper” (banded and spherulitic rhyolite) in Vermont and New Hampshire, eastern Pennsylvania, and Machiasport, Maine; Mt. Kineo felsite in Maine; and Onandaga and Normanskill cherts in upstate New York.[6] Bands relied on their prey herd for everything—food, clothing, bone and ivory tools, and even shelter, using antlers and rib cages as frames for the rock-bound hide-covered pits in which they sheltered. They were dug into permafrost and lined with rocks on land exposed after ice sheet retreat[7] Remains of Paleoindian pit houses have been found on the former shores of glacial lakes. The people gathered seasonally at sites where mass kills were possible, taking the animals when they forded waterways at chokepoints; or became trapped on peninsulas, offshore islands or barrier beaches; or were swimming in the water and therefore unable to stampede to get away. Paleoindian caribou hunters used the same kill site methods that First Peoples of Canada traditionally use today.[8]

Pit house, Nunavut Canada (Creative Commons)

Caribou Migration in Alaska (National Park Service photo)

The Bull Brook site

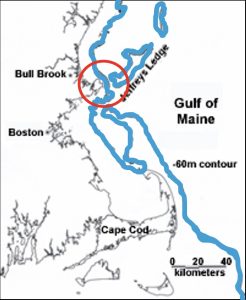

One such kill site was on Bull Brook in Ipswich, to date still the largest Paleoindian site in all of North America. It was occupied repeatedly over a long period around 11,500 years ago. Bull Brook was a salvage excavation begun by amateur archaeologists in the 1950s and continued in the 1970s. They found 36 house-sized activity areas arranged in a ring-shaped pattern covering an area of 170 x 135 meters. More than 8,000 artifacts and myriad deposits of caribou bones were found at Bull Brook, which featured more than 40 concentrations of stone artifacts at butchering sites. Archaeologists hypothesize that Bull Brook was occupied seasonally by the same bands of people over hundreds of years.[9] Bull Brook is located near a caribou migration chokepoint between the island of Jeffrey’s Ledge and the mainland on the ancient shoreline of Ipswich. Jeffrey’s Ledge, now submerged, was dry land, making the bottleneck a prime location for a cooperative kill site. The map below shows this chokepoint, with the blue line indicating how the shoreline would have looked 11,500 years ago.

Bull Brook map[10]

Professional re-analyses in the 1990s and 2000s concluded that Bull Brook was a seasonal settlement of 6 to 8 bands of people who came together annually over 300 years or more, probably for the cooperative herding and hunting of caribou. Archeologists can estimate band size and organization and population size from habitation patterns. Anthropologists define a band as an extended family or kin group numbering 20 to 40 people, so the annual gathering at Bull Brook likely involved 120 to as many as 320 individuals. At the annual cooperative hunt, the people processed meat and hides and likely feasted, introduced new family members, remembered those who had died, chose marriage partners, shared information, traded stones and tools and crafts, and celebrated their survival. Then, dividing the spoils of the hunt, they split up into their separate bands and moved off to forage for their livelihoods the rest of the year.[11]

The largest collection of Bull Brook artifacts is stored in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. Bull Brook is now just a gravel pit on private property, but its artifacts and other Paleoindian finds from Essex County may be seen at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University in Cambridge, the Peabody Archaeological Institute at Phillips Academy in South Andover, and the Massachusetts Archaeological Society’s Robbins Museum in Middleborough.

Other evidence of Paleoindians in Essex County

There is some evidence of Paleoindians on Cape Ann, and there would be much more if our shores had not been inundated by 60 to 100 meters (197 to 328 feet) of sea since the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet around 8,000 years ago.[12] Individual specimens of Paleoindian spear points and polyhedral (pyramidal) cores have been found in Annisquam, Magnolia Beach, Ipswich, Andover, Peabody, Newbury, and Plum Island. Evidence is more abundant for other parts of New England.

Paleoindian spear points from Annisquam (Gloucester), Bull Brook (Ipswich), Great Neck (Ipswich), and Plum Island (Newbury)[13] (Used with permission.)

Changes in the land at the end of the Pleistocene

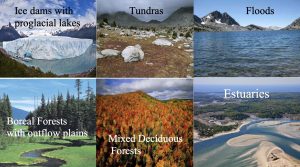

The Paleoindians and their prey disappeared as rapidly as they spread, as a consequence of catastrophic climate change and predation of megafauna exceeding carrying capacity. We know this from studies in both historical geography and paleontology. Historical geography traces changes in land and sea environments caused by both natural and human agencies. These changes affect human history by causing changes in terrains, species distribution, exploitable living areas, food resources, and access to resources such as water and vegetation. Deglaciation permitted the occupation of New England, for example. But after just a few thousand years Paleoindian times ended as the Pleistocene ended. The climate warmed rapidly, glaciers melted and glacial lakes drained, then refilled and drained again, causing catastrophic flooding and raising the sea level to such an extent that ocean currents changed, causing the climate to cool again and the land to refreeze. Warming then resumed and continues to this day. At the same time as sea level rose, the land also rose as it was relieved of the weight of the glacier, and the land dried and became forested. Boreal (evergreen) forests and grasslands rapidly replaced the tundra, and tundra-adapted plants and animals rapidly became extinct along with people who specialized in hunting them.[14] Evidence from Pleistocene archaeology and paleontology suggest that the rate of predation of megafaunal species through specialized hunting, especially mammoths and mastodons, exceeded their rates of reproduction, contributing to their eventual extinction.

Scope of Environmental changes at the beginning of the Holocene

The climatic change from tundra to boreal forest led to greater diversity and abundance of plants and supported a greater number of more territorial animals rather than migrating ones.The new environments at the end of the Pleistocene and beginning of the Holocene favored diverse small game, fowl, fish, and shellfish. Diverse, abundant, and localized food resources supported more people and permitted more localized human settlement. So, as the world changed, people adapted their technologies and cultures to thrive in it as best they could. And it is ever thus. Environmental change and human adaptation are deeply interrelated throughout human history. Even on Cape Ann. Even now. Despite its continuing post-glacier rebound, Cape Ann and the East Coast generally are vulnerable to sea level rise. The highest points, Mt. Ann and Thompson Mountain in West Gloucester, are only 256 Ft. (78.03 meters) and 154 feet (46.94 meters) above sea level respectively. Gloucester as a whole has an average elevation of only 10 feet above sea level. If the sea level rose 6 meters, those “mountains” in West Gloucester, along with parts of Dogtown, would be all that remained. They would be islands in the sea off Massachusetts.[15]

Evidence of sea level rise on Cape Ann can be seen today in higher high tide levels, increased storm damage; drowned mouths of rivers and streams, and remains of drowned ancient forests on the beaches, for example, near Brier Neck and behind Little Good Harbor. Sand dunes, barrier beaches, salt marshes, wetland spawning grounds, and shellfish beds may be at most immediate risk of damage from sea level rise, along with fresh water habitats such as Niles Pond, which is separated from the sea only by a narrow berm of land that residents have maintained over the generations.

Catastrophic climate change

The melting of ice sheets at the end of the Pleistocene produced vast wetland environments throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Icemelt also created an enormous freshwater lake right in the middle of Canada—Lake Agassiz, which no longer exists–named for a Swiss geologist, Louis Agassiz.[16] The lake gradually drained out around 12,800 to 13,000 years ago, then refilled, and then around 8,400 to 8,200 years ago emptied again in a great flood. A glacier moves on a thin sheet of icemelt caused by its great weight and friction as it moves downhill, obeying the laws of gravity. Glaciers trap water, even whole lakes, inside them. The water is held in by the hard ice on the glacier’s leading edge. These outside edges act as a dam. If the dam fails, all the water explodes out and floods the land. Catastrophic floods like this occurred all over the Northern Hemisphere just as people were beginning to build the ancient Old World civilizations. A Great Flood figures nearly universally in Eurasian and North American origin stories and folktales.[17]

Lake Agassiz

Lake Agassiz’s outflows carved the Missouri-Mississippi, Ohio, St. Lawrence, Hudson, Delaware, and Connecticut River valleys. The first time Lake Agassiz drained out into the Arctic Ocean, Hudson Bay, North Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico, it raised the sea level by one meter in a single year and 35 meters (115 feet) in all. So much cold fresh water entered the sea that the ocean currents changed. The warm Gulf Stream changed course, causing a new mini-ice age in the North Atlantic, called the Younger Dryas. The Younger Dryas lasted a thousand years and ended around 11,500 years ago, just as quickly as it started. These rapid environmental cycles of warming, flooding, loss of vegetation to fire and flood, and sudden cooling contributed to the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna.[18] We see a significant change in the archaeological record. Deposits above the lacustrine layer (glacial lake sediments) are strikingly different from the deposits below it. The bones of mammoths, mastodons, dire wolves, American lions, horses, camels, and many other large mammals are not found in layers above the ancient lakebeds, and the fluted points called Clovis that the Paleoindians made are not found there either.

Some scientists define global warming at the end of the Pleistocene as an extinction event. A thin layer of carbonized organic material (a “Black Mat”) with rare trace minerals overlies Clovis sites, begging the question of what caused the global warming in the first place. The Black Mat may represent more than just the natural decomposition of drowned wetland environments[19]. It has been postulated that around 11,500 or 12,000 years ago a comet or meteorite exploded in the atmosphere over Canada, or struck, melting the remaining ice sheet, liquefying the ice dams holding water within it. Water evaporated or drained away leaving extensive wildfires, die-offs of vegetation, and drought, accounting for all the carbon found, along with the layer of rare minerals laid down by the explosion or impact. The recent discovery of an asteroid strike in Greenland’s Hiawatha Glacier dating to the same period supports this theory.[20]

It’s sometimes hard to grasp the sweep of time. Things seem to have happened so long ago, yet so recently, and they often seem to have happened more than once. I find it helps to think of time in terms of the equivalent in human generations. For example, 20,000 years—the time between now and the peak time of the last glacier over Cape Ann—is about the same as 800 generations in the human family, the “huddled masses”. In the last 10,000 years since the end of Paleoindian times in New England, 400 generations have passed—so many, so few, in such a long, short, time. It’s just me with my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren a mere 100 times over, making 10,000 years seem like a drop in the bucket. History is endlessly deceptive in this way, amazing us with what happened only just yesterday so very long ago. In the end, however we shave it, we don’t really grasp time. Our self-importance, both individually and as a species, prevents us, perhaps, from appreciating just how fleeting and insignificant we really are in the grand scheme of things.

In most sites the archaeological record shows a gap of up to a thousand years between Paleoindian occupations at the end of the Pleistocene and the sites of people of the Archaic Period who followed them. It is not clear if the Archaic people, who repopulated and transformed the Northeast, were new migrants or descendants of small cohorts of Paleoindian survivors.[21] In any case, Cape Ann and other places in Essex County have extensive evidence of Archaic Period occupation. Who were the Archaic Period people, what made them different, and how did they live here?

Back to “What People Lived In Essex County, and When?”

Notes and References

[1] Lothrop, Jonathan C., Darrin L. Lowery, Arthur E. Spiess and Christopher J. Ellis. 2016. Early Human Settlement of Northeastern North America. PaleoAmerica 2 (3): 192-251. A perspective on the role of Clovis technology in understanding the peopling of the Americas is given in an online article from Archaeology Magazine by Nikhil Swaminathan: Destination: The Americas (August 10, 2014), at http://www.archaeology.org/issues/145-1409/features/2367-peopling-the-americas-paradigms. The presence of mastodons on Cape Ann is attested in John Sears’ The physical geography, geology, mineralogy and paleontology of Essex County, Massachusetts and in Peter Gleba’s Massachusetts Fossil and Mineral Localities. Read about the mastodon bones and teeth dredged from Stellwagen Bank on the web site of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, http://stellwagen.noaa.gov/about/geologic.html, which reprints Robert Oldale’s article: Geologic origins of Stellwagen Bank, from The Cape Naturalist,1993-94.

[2] See, for example, Joyce, D. J, 2013. Pre-Clovis megafauna butchery sites in the Western Great Lakes Region. In K. E. Graff, C. V. Ketron and M. R. Waters, eds. Paleoamerican Odyssey. College Station, Texas, Center for the Study of the First Americans, pp. 467-83; also Brook, Barry W. and David M.J.S. Bowman. 2002. Explaining the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions, Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences 99 (23): http://www.pnas.org/content/99/23/14624.full.

[3] See David Anderson’s chapter on Paleoindian Interaction Networks in the Eastern Woodlands in Native American Interactions: Multiscalar Analysis and Interpretations in the Eastern Woodlands (1995) by Michael Nassaney and Kenneth Sassaman, eds. Also Ellis, Christopher J. 2004. Understanding “Clovis” Fluted Point Variability in the Northeast: A Perspective from the Debert Site, Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 28 (2): 205-253. For more on Paleoindian mobility over great distances for source stone, see Burke, Adrian, (1988), Paleoindian ranges in northeastern North America based on lithic raw materials sourcing: 116, in ResearchGate.

[4] The painting is by Velizar Simeonovski for a 2012 exhibit (Mammoths and Mastodons: Titans of the Ice Age) at the Field Museum of the Museum of Science in Boston.

[5] The red line indicates the farthest advance of ice during the last glacial period. The retreating glacier left huge pro-glacial lakes. Lake Champlain was still part of the North Atlantic Ocean. The Merrimack River originally emptied at Salem Sound; then, because of elevation of the land after glacial retreat, it emptied first at Ipswich, and today at Newburyport. The original map is from Antevs, Ernst V., 1922,The recession of the last ice sheet in New England. American Geographical Society Research Series No. 11, American Geographical Society, NY. Antevs’ map and the map of post-Pleistocene lakes in New England are both reproduced on the website of Tufts University’s North American Glacial Varve Project, History of Glacial Varve Chronology: Eastern North America, which also has an excellent bibliography on the subject, at http://eos.tufts.edu/varves/History/history2.asp. Over Essex County the Laurentide Ice Sheet was at least 2,290 feet thick (or 804,672 meters, just under half a mile) at its thickest point. A source for the depth of ice over Cape Ann is Margaret Martin, Glaciation of the Massachusetts Coast (2008). Sources on submerged prehistoric sites on Cape Ann include Possible Shipwreck and Aboriginal Sites on Submerged Land (in) Gloucester Massachusetts (1998) by Warren C. Riess: http://www.mass.gov/czm/dredgereports/1998/dmmp-98-02.pdf; Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf (2012) by the U.S. Department of the Interior; and Maritime Cultural Resources of Massachusetts Bay: The Present State of Identification and Documentation (1990) by the Massachusetts Bay Marine Studies Consortium. The Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) has on file several archaeological surveys of possible underwater archaeological sites on Cape Ann, for example, Alan Leveillee’s 1988 Intensive archaeological survey of the proposed Essex Bay Development Area, Gloucester, MA (MHC 829). See also Archaeological Potential of the Atlantic Continental Shelf (1966) by K. O. Emery and R. L. Edwards in American Antiquity 31(5), and Ed Bell’s article in Coastal Management 17 (2009): Cultural resources on the New England coast and continental shelf: Research, regulatory, and ethical considerations from a Massachusetts perspective. Sources for the effects of glacial action on Cape Ann include, in addition to Margaret Martin’s work, Nathan Shaler’s The Geology of Cape Ann, Massachusetts (U.S. Geological Survey Annual Report 9, 1890); John Sears’ The physical geography, geology, mineralogy and paleontology of Essex County, Massachusetts (1905); Raymo and Raymo’s Written in Stone: A Geological History of the Northeastern United States (2001); and the Interpreter’s Notes—Geology Rocks! (2007) at Halibut Point State Park: http://halibutpoint.wordpress.com/2007/07/01/interpreters-notes-geology-rocks/. The information on glacial till comes from the United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service (1984): Soil Survey of Essex County, Massachusetts, Southern Part, available at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MANUSCRIPTS/massachusetts/MA606/0/Essex.pdf .

[6] For example, see Lowery, Darrin L. 2017. Ramah Chert A Lithic Odyssey 2017 Chesapeake Bay Region Pdf. Loring, Stephen. 2002. “And They Took Away the Stones from Ramah”: Lithic Raw Material Sourcing and Eastern Arctic Archaeology: Loring2002.pdf. Also in Honoring Our Elders: A History of Eastern Arctic Archaeology, William Fitzhugh, Stephen Loring and Daniel Odess, eds. Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 2: 163-185 (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC).

[7] Sub-arctic house floors of Dorset and Thule peoples resemble paleoindian pit houses. See, e.g.: https://people.wku.edu/darlene.applegate/newworld/webnotes/unit_2/arctic_cultures.html.

[8] Principal sources include Reindeer and caribou hunters: An archaeological study by Arthur Speiss (1979), Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (2009) by Olive Dickason, and papers presented at the 2013 Eastern States Archaeological Federation Annual Meeting in South Portland, Maine, by Luc Litwinionek and Lynn Peterson (Optimal foraging, least cost pathways and Early Paleoindian colonization of the far northeastern United States) and by John Crock et al. (Reconstructing Paleoindian Settlement, Travel and the Cognitive Landscape within the Champlain Valley of Vermont).

[9] Read about the original discovery and excavation of Bull Brook by amateur archaeologists William Eldridge and Joseph Vaccaro in the July 1952 issue of the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 13 (4): 39-43 (The “Bull Brook” Site, Ipswich, Mass.). Professional archaeologist Douglas Byers followed up in 1954 (Bull Brook—A Fluted Point Site in Ipswich, Massachusetts) in American Antiquity 19 (4). The diagram and map of Bull Brook are based on figures given on the web site of the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine (2009): Contribution 11: Archaeology at the Bull Brook Site. In Paleoindian Mobility and Aggregation Patterns: http://climatechange.umaine.edu/.

[10] Base map is Courtesy of the Climate Change Institute: http://www2.umaine.edu/climatechange/Research/Contrib/html/11.html.

[11] Reinterpretations of Bull Brook began around 1980. See John Grimes, A New Look at Bull Brook, Anthropology 3 (1979), and Grimes et al. (1984): Bull Brook II, in Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 12. The most recent interpretation of Bull Brook as a caribou kill site at a chokepoint on the Agawam coast was put forth by Brian Robinson et al. (2009), Paleoindian aggregation and social context at Bull Brook, in American Antiquity 74 (3). Brian Robinson most recently gave a talk with Jennifer Ort (November 2013) on Paleoindian Aggregation Patterns in Northeastern North America: Analysis of the Bull Brook Site, Ipswich, Massachusetts, at the Eastern States Archaeological Federation Annual Meeting in South Portland, Maine. Robinson is the leading expert on Bull Brook today and on the artifacts from Bull Brook that are in storage at the Peabody Essex Museum. I had the privilege of examining this collection in fall 2014.

[12] Donnelly, Jeff. 2001. Sea Level Rise (in Massachusetts). Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute: http://www.geo.brown.edu/georesearch/esh/QE/Research/CoastStd/SeaLevel.htm. See also Possible Shipwreck and Aboriginal Sites on Submerged Land (in) Gloucester Massachusetts (Riess 1998), and a 1990 report of the Massachusetts Bay Marine Studies Consortium, Cultural Resources Committee, Maritime Cultural Resources of Massachusetts Bay: The Present State of Identification and Documentation. Examples of environmental impacts of sea level rise are found in Holocene Sedimentary Evolution of the Merrimack Embayment, Western Gulf of Maine (2006) by C. Hein et al., available online (Merrimack River Geology pdf) and in Dean Snow, 1972, Rising sea level and prehistoric cultural ecology in northern New England. American Antiquity 37 (2): 211-222.

[13] The Annisquam point is courtesy of the Annisquam Historical Society, photo by M. E. Lepionka. The Bull Brook point is in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum; and the Great Neck and Plum Island points are courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Parker River Wildlife Association.

[14] Climate change is summarized in Christopher Scotese’s Climate History Paleomap (2002) at http://www.scotese.com/climate.htm. For environmental impacts of sea level rise, see Dean Snow’s article (1972), Rising sea level and prehistoric cultural ecology in northern New England, in American Antiquity 37 (2).

[15] Sources on submerged prehistoric sites on Cape Ann include Possible Shipwreck and Aboriginal Sites on Submerged Land (in) Gloucester Massachusetts (1998) by Warren C. Riess, and Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf (2012) by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The Massachusetts Historical Commission has on file several archaeological surveys of possible underwater archaeological sites on Cape Ann, for example, Alan Leveillee’s 1988 Intensive archaeological survey of the proposed Essex Bay Development Area, Gloucester, MA (MHC 829). See the article, Archaeological Potential of the Atlantic Continental Shelf (1966) by K. O. Emery and R. L. Edwards in American Antiquity 31(5), and especially Ed Bell’s article in Coastal Management 17 (2009): Cultural resources on the New England coast and continental shelf: Research, regulatory, and ethical considerations from a Massachusetts perspective. Projections of impacts of sea level rise on Cape Ann in the future appear on the web site of the Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, for example, Coastal Shore Protection Structures and Techniques and Map of Anticipated Response to Sea Level Rise in Coastal Massachusetts (2006): http://chl.erdc.usace.army.mil/chl.aspx?p=s&a=Articles;199 . Also the USGS has interesting data on Cape Ann’s mitigating crustal rise (postglaciation rebound) in relation to sea level rise. See also Archaeological Potential of the Atlantic Continental Shelf (1966) by K. O. Emery and R. L. Edwards in American Antiquity 31(5), and Ed Bell’s article in Coastal Management 17 (2009): Cultural resources on the New England coast and continental shelf: Research, regulatory, and ethical considerations from a Massachusetts perspective.

The presence of mastodons on Cape Ann is attested in John Sears’ The physical geography, geology, mineralogy and paleontology of Essex County, Massachusetts and in Peter Gleba’s Massachusetts Fossil and Mineral Localities. Read about the mastodon bones and teeth dredged from Stellwagen Bank on the web site of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, http://stellwagen.noaa.gov/about/geologic.html, which reprints Robert Oldale’s article: Geologic origins of Stellwagen Bank, from The Cape Naturalist,1993-94.

[16] The widely reproduced map showing the outflows of Lake Agassiz comes from an article by D. B. Murton et al. at Sheffield University in the UK: Identification of Younger Dryas outburst flood pathway from Lake Agassiz to the Arctic Ocean, in the April 2010 issue of Nature. For more information on the Younger Dryas and other abrupt climatic changes of the Holocene, see NOAA’s Paleoclimatology page on the National Climatic Data Center web site: http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/abrupt/data4.html.

[17] For an appreciation of the near universality of flood and mud myths and legends, passed down in diverse cultures since the end of the Younger Dryas, see Mark Isaak’s web site, Flood Stories from around the World, at http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/flood-myths.html.

[18] The case for extinction theories based on human over-hunting is well presented in an article by Barry Brook and David Bowman, Explaining the Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction, in Proceedings of National Academy of Science 99 (23): http://www.pnas.org/content/99/23/14624.full. The case for extinction theories based on climate change is given in A Requiem for a North American Overkill, Journal of Archaeological Science 30 (2003): http://faculty.washington.edu/grayson/jas30req.pdf. I agree with moderates who include both models along with the Black Mat Theory and new data from paleo-epidemiology about disease factors. There is no reason that all these things could not have been factors in the massive changes that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene.

[19] The Black Mat theory is explained in R. B. Firestone et al., Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2007): 104 (41): http://www.pnas.org/content/104/41/16016.abstract.

[20] Kuaer, Kurt H., et al. 14 Nov. 2018. A large impact crater beneath Hiawatha Glacier in northwest Greenland. Science Advances 14 Nov 2018: Vol. 4, no. 11, eaar8173. Also Voosen, Paul. 14 Nov. 2018. Massive crater under Greenland’s ice points to climate-altering impact in the time of humans: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/11/massive-crater-under-greenland-s-ice-points-climate-altering-impact-time-humans.

[21] See, for example, Anderson, David G., M. Ashley, M. Smallwood, and D. Shane Miller. 2015. Pleistocene human settlement in the southeastern United States: Current evidence and future directions. PaleoAmerica 1 (1): 7-51. Bousman, C.F., et al. 2002. The Palaeoindian-Archaic transition in North America: New evidence from Texas. Antiquity 76: 980-990.