People of the Early Woodland Period first migrated into New England and the Atlantic coastal plain from the northern shores of the Great Lakes and the Ottawa and St. Lawrence valleys, beginning around 3,500 years ago. They likely replaced or absorbed or were absorbed by the Coastal Archaic populations that were already living here, which would account for the Late Archaic-Early Woodland sites containing mixes of technologies from both periods. Later larger waves of the Middle Woodland Period came from the southern shores of the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Susquehanna valleys around a thousand years ago. They are the ones who brought the maize that had been domesticated in northern Mexico much earlier, as early as 8,000 years ago, and carried up the Mississippi Valley. They also brought tool blocks in types of stone not found in New England (such as Minnesota pipestone, obsidian, Lake Michigan and Ohio flint, and Onandaga chert), as well as the practice of burying their dead in mounds. They spread along the river systems of the Northeast and their tributaries—the Hudson, Connecticut, Blackstone, Shawsheen, Concord, Ipswich, Parker, Merrimack, and others. These later Woodland people absorbed, joined, and/or replaced those who had gone before–for human history is full of population movement, periodic migration, invasion and succession, expansion and contraction, and none of us is where our ancestors were before us, nor theirs before them.[1]

Woodland population movement[2]

The Eastern Woodland Indians spanned the Northeast from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic and from the Canadian Maritimes to Chesapeake Bay. They also spanned the Southeast from the Mississippi to the Atlantic and from Chesapeake Bay to Florida. The peoples living in the Northeast and the Southeast shared similar technologies because they had adapted to similar environments—mixed deciduous forests with lakes and estuaries connected by rivers. In other ways, their histories and cultures diverged. Early Maritime Woodland people in New England made their living by hunting, trapping, fishing, fowling, clam digging, and gathering. They primarily hunted white-tailed deer, elk, moose, and small game. They used bows and arrows, snares, and spears and drove animals into fenced funnels leading to spring traps and kill sites. Bows and arrows called for microlithic projectile points and spokeshaves for smoothing and finishing arrow shafts. Ash was preferred for bows and dogwood for arrow shafts. On the coastal plain and in the estuaries of tidal rivers—among the richest ecosystems on Earth—a mixed economy with fish and shellfish and intensive horticulture, in addition to traditional hunting and gathering, enabled people to produce the surpluses needed to establish larger populations with more permanent settlements.[3]

Some Woodland Period sites in Essex County[4]

Woodland Period Technologies

Distinctive lithic styles of the Woodland Period include small stemmed points and triangular points, especially of quartz, chert, rhyolite, and felsite, diagnostic of the period. The people used locally and regionally available stones—the nearest sources of chert were in Peabody and Rowley, for example—but they also maintained an extensive east-west trading network, acquiring exotic stone from the Great Lakes and Southwest regions in exchange for gifts of the sea. Atlantic seashells have been found in Ohio burial mounds, for example. Late Woodland peoples east of the Appalachians in the Ottawa Valley (e.g., Algonkin), St. Lawrence (e.g., Huron/Wendat), upstate New York (e.g., Iroquois), and eastern Pennsylvania (e.g., Susquehannock) served as intermediaries in trade between people on the East Coast and the those west of the Appalachians. Late Woodland intermediaries in the coastal trade for furs, corn, and tobacco were the Montagnais, Abenaki, Narraganset, and Delaware.[5]

Woodland people mined, quarried, collected, or traded for quartz, jasper, serpentine, greenstone, hornblende, marble, slate, copper, and malachite to be ground or polished for projectile points, beads, effigies or figurines, pendants, breastplates, and pipes. Woodland lithics also included agricultural tools such as mortars and pestles, grinding stones and mullers, hoes, and hand tools for troweling, as well as tools for woodworking, weaving, chopping fibrous plants, opening clams, and processing meat and fish. In southern New England the presence of agricultural tools and preserved residues of domesticated plants identify Late Woodland sites.

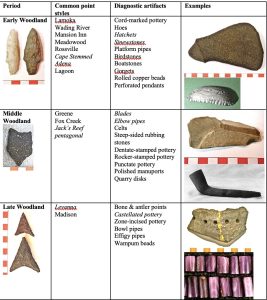

Technologies of the Early, Middle, and Late Woodland Periods[6]

Bone, antler, and wood were equally important as stone, for example, as handles for stone hand tools, such as knives. The people also used bone, antler, and wood in the process of pressure flaking for the production of stone tools; for fishing gear—compound hooks and fish spears; for hide processing—awls and eyed needles; for making shell beads—burins and punches; and for inscribing on bark or clay. Shell, easily carved, also had multiple uses, beginning with the production of beads and combs. On Coffin’s Beach and Cole’s Island in West Gloucester the people limed their corn hills of imported soil with broken shells, which both sweetened and stabilized the acidic and sandy soil. They hafted bone handles onto surf clam shells to make clam rakes and trowels for cultivating their gardens, and they fashioned the shiny interiors of shells—the nacre—into adornments and embellishments to be worn or sewn into clothing.

Examples of Late Woodland lithics from Cape Ann[7]

Pottery

The Woodland people used crushed shells, plant fibers, ground quartz, and crushed mica to temper brittle local marine clays in the production of pottery. Woodland Period sites on Cape Ann were reported as having pits for firing pots and huge quantities of potsherds. For example, in 1920s and 30s Frank Speck, Frederick Johnson, and N. Carleton Phillips removed several hundreds of potsherds from firing pits in three large pottery manufacturing areas on the Riverview peninsula in Gloucester alone. Other cultural deposits with ceramics have been found in Annisquam, West Gloucester, and Essex.[8] Extensive production of large, thick pottery vessels used in cooking with volumes of water is diagnostic of the Woodland Period.

The potters kneaded the clay and rolled it into ropes to be coiled up, joined, shaped, and smoothed. They then added rims to wet pots, ranging from simple to ornate, and often finished them by marking or decorating them in some way. Whacking the clay with cord-wrapped paddles left distinctive impressions both inside and outside a pot. Rims and necks of pots were given special attention. Decoration included fingernail or stick incisions of lines, curves, dots, zigzags, and chevrons, as well as impressions using carved stamps or woven fabrics pressed into the damp clay. Some pots were punctured in a few places just below the rim before firing them, making holes to aid in hanging them over a fire or inserting wooden pegs as handles to lift them on and off the hearth.

Eastern Woodland ceramics decorative styles[9]

Pots were air dried for several days and then wood-fired in the open—propped among stones in sand pits, packed all around with wood, and set ablaze. The clay baked an orangey red or yellow because of the presence of oxygen (pots fired in ovens or kilns in the absence of oxygen bake black). Open firing was at low temperatures, making the pots fragile. Those used for cooking with water had to be made extra thick to withstand thermal shock. The bottoms of pots were pointed or oval-shaped to rest between stones over a fire or to prop in sand in a storage pit. Preserved foodstuffs were cached in pots in underground storage chambers at various occupation sites rather than carried from site to site.[10]

In Essex County, Woodland peope and later the colonists dug extensive clay deposits in Danvers, Ipswich, Newbury, Boxford, Salisbury, Lynn, and Saugus. Gloucester also has local sources of clay. Other than Clay Pit Landing in the Jones River, Pavilion Beach, Cambridge Beach in Annisquam, and Pebble Beach in Lanesville also had accessible deposits of marine clays. The Woodland Indians also traded special kinds or qualities of clay, such as kaolin, a fine-grained white clay quarried locally in Newbury and Essex, also used in the making of white body paint. Clays were sometimes added to other ground paint stones as well, such as red and yellow ochres mined in Beverly, Georgetown, and Rowley, and graphite, for black paint, obtained in Middleton or through trade with Nipmuck people living in the Sturbridge area south of the Quabbin watershed.[11]

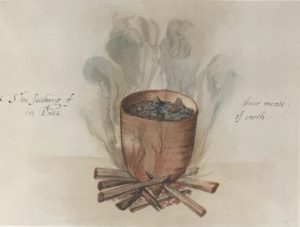

Bulk cooking with water[12]

Changes in the composition of ceramics, the type of temper used—such as plant fibers, ground quartz, macerated shell, crushed pottery, or sand—and changes in decorative styles identify different cultural traditions or times. For example, grit- or sand-tempered pottery replaced quartz and fiber-tempered pottery in the Late Woodland period, and pots became larger and thicker for cooking with large volumes of water, as in the boiling of stews with meat or fish and corn, squash, and beans.[13] In addition to making clay pots for boiling over a fire, clay was used in wigwam flooring, creating fire brakes for controlled burns, waterproofing, lining for cache pits, and encasing for open-fire baking. Changes in ceramic styles help in the relative dating of Woodland Period sites.[14]

Some Eastern Woodland ceramics[15]

Stone projectile points and clay potsherds are the stuff of archaeological finds, because they are readily preserved, even in New England’s acid soils. But even more significant in the daily lives of the Eastern Woodland people may have been their use of wood and plant fibers, items less well preserved and more rarely found. Wood submerged in water may last practically forever, as in the 5,000-year-old willow, alder, and sassafras fish weir found in 1939 under Boylston Street in Boston’s Back Bay. Ancient fibers are harder to come by, however, although bits of cordage and impressions of basket weave may be seen in clayey earth.

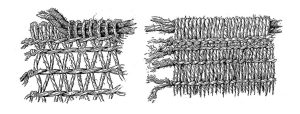

Fabric remains from Manchester-by-the-Sea[16]

Uses of Woods and Fibers

Wood had many uses. Women used hollowed tree trunks as containers to process tree sap for syrup and to pound corn. Men hollowed out oak tree trunks for dugout canoes and stripped and steam-shaped birch cambium for bark canoes. Individual trees were specially designated and preserved for purposes such as these. Woods and fibers were also essential for bows and arrows, cordage, and wigwam frames and coverings. The inner bark of trees and mast from the stems of marsh plants were used to make twine for weaving traps, snowshoes, fabric, nets, mats, baskets, and rope.

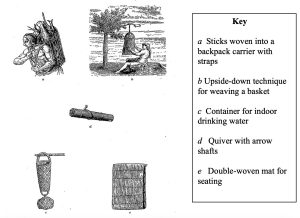

Champlain expedition’s drawings of products created from fibers

Examples of Late Woodland wood and fiber crafts[17]

Fibers joined the parts of compound tools and hafted handles to implements of all kinds so they could be wielded. As observed by Daniel Gookin (1674: 152), for example:

The tools they used in preparing the ground and in cultivation were usually wooden spades or hoes, the latter being made by fastening to a stick, as a handle, a shell, the shoulder blade of an animal, or a tortoise shell…. Their pots were made of clay, somewhat egg-shaped; their dishes, spoons, and ladles of wood; their water pails of birch bark, doubled up so as to make them four-cornered….

The axe or hatchet, called the tomhegun or tomahawk was made of granite or slate, and had a groove cut around it near the head–instead of an eye, and which held the handle. The handle was a mere withe, or sapling, so pliant as to be bent around the axe, in this groove, and was then fastened or tied with the roots of the spruce…..

Lashings made of plant fibers or tree roots were generally preferred to animal sinews, which were more labor intensive. Tendons from the legs and spine of large animals had to be cleaned, cured, stretched, staked, dried, and softened. Re-stiffened with bees’ wax, sinews made good thread for sewing hides together and for lacing and beading work, but their tendency to stretch when wet made them a poor choice for hafting most stone tools unless they were applied stretched and wet and then allowed to dry and shrink around the stone. Axes could also be hafted by inserting the stone into living wood, as Daniel Gookin marveled:[18]

They selected a small, straight hickory, oak, or other tough sapling of the proper size, and splitting it as it stood, thrust the stone axe through the cleft till the parts closed around the axe, in the groove made for that purpose. They there left it till such time as the sapling, in its growth, enclosed the axe firmly within its wood. The sapling was then cut at the proper length, and fashioned into shape according to the taste and skill of the owner.

Imagine having the patience to let living wood grow around the business part of your axe, like old trees embedding chain-link fences into their flesh on the perimeters of old schoolyards.”With this axe,” Gookin concludes, “the people felled their trees, cut their wood, chipped and formed stones into other axes, dug up bushes and roots, and formed the hills for the reception of their seed-corn and other vegetables.

A hoe or mattock or shovel could be made by hafting a wooden handle to the scapula of a large animal, such as a moose, rather than a stone blade.[19] Shoulder blades made good light-weight shovels for short-term use, such as shoveling heated rocks, coals, and ashes—and hafted moose antlers made good clamming forks.

Moose shovel and lashed axe[20]

Fiber crafts could carry water, snare deer, net fish, cradle infants, weave baskets, haft weapons, and fortify encampments. Prized plants for fibers included “Indian hemp”, or dogbane (Apocynum cannibinum).

Plants used for fibers[21]

On seeing “Indian hemp” (dogbane, Apocynum cannibinum), Champlain remarked, “They told me that they gathered this plant without being obliged to cultivate it, and indicated that it grew to the height of four or five feet.” Champlain observed hook and line fishing in his diary:[22]

…They catch with hooks made of a piece of wood, to which they attach a bone in the shape of a spear, and fasten it very securely. The whole has a fang-shape, and the line attached to it is made out of the bark of a tree. They gave me one of their hooks, which I took as a curiosity. In it the bone was fastened on by hemp….

William Wood observed that this Indian hemp made much stronger cordage for fishing nets and lines than what the English had.[23]

[Since] the English came they be furnished with English hookes and lines, before they made them of their owne hempe more curiously wrought, of stronger materials than ours, hooked with bone hookes….[They] make likewise very strong Sturgeon nets with which they catch Sturgeons of 12. 14, and 16. some 18. foote long in the day time….Their cordage is so even, soft, and smooth, that it lookes more like silke than hempe; their Sturgeon netts be not deepe, not above 30. or 40. foote long.

Hemp figured into the construction of every technology used in the daily life of people of the Woodland Period. Cordage was made by twisting fibers together by rolling them against the thigh to make and join strands. Women used spindle whorls as weights to enlist the aid of gravity in spinning bast fibers into thread. Women also used heart-shaped palm tools for weaving. They used the notched end to straighten unruly fibers and the pointed end to poke fibers into the weave.

Dried hemp stalks, bast fiber, and spindle whorl[24]. Women’s weaving tools[25]

Styles of weave[26]

Basketry

Baskets were ubiquitous in Eastern Woodland life. Different types of baskets, made of bark and fibers by both men and women, were used to store dried foods, serve as vegetable steamers, contain special herbs or sacred objects, and even carry water. Baskets could be made waterproof because of the tendency of wood and fibers to swell when wet–also useful to later colonial coopers making barrels with wooden staves. Rectangular lidded baskets made of folded birchbark also could carry water. Baskets made from strips from the inside bark of ash trees (the wood between the bark and the pith) were particularly strong and could be used as backpacks, quivers, crab traps, and clam baskets.

Plant fibers for basketry on the Northeast coast included sweetgrass, beach grass, eelgrass, and strips of inner bark of ash and willow. Aromatic sweetgrass was also used in incense, prayer aids, necklaces, smoking mixtures, tea, decorative trim for cradleboards, and medicine bundles. Small, coiled baskets could also be made from pine needles or sedge. [27] For coiled sweetgrass baskets, women collected the grass in June or July and soaked the sheaves in water so they could bend without breaking. They then wrapped the sheaves with twine or lashing into long rolls and built them up in coils, lashing each coil to the one below it and at the same time shaping the basket. The final shape of the basket held when the grass dried.

Plants for Basketry and coiled basket making [28][29]

They decorated their baskets, wooden things, clothing, and bodies with paint made from plant dyes as well as from ground minerals. For fabric, the cloth was first soaked and boiled in a fixative—salt water for berry dyes and grape vinegar for plant dyes.[30] For body paint and tattoos, they mixed vegetable dyes with ashes and seed oils, bear fat, or fat from seals or other marine mammals. They also dyed fabrics, yarns, porcupine quills, and squirrel tails for decorative needlework.

Some sources of Native vegetable dyes in Essex County

For decoration, Algonquian design motifs were based on important shapes or features in their environment, such as curving trail lines, hills or wigwam domes, berry or rock clusters, spots or dots, flower petals, sprays of foliage, and abstract forms such as contrasting diagonal lines. Women used these motifs in painting, ornamenting, beading, embroidering, and weaving with fibers. These design motifs and fiber arts were combined with disks of shell nacre, polished groundstone or minerals, leathers, furs, pounded copper pendants, shell and stone beads, pearls, quills, animal teeth, antler slices, and feathers in clothing, headdresses, and jewelry.

Design Motifs in Algonquian Art.

Examples of decorative arts[31]

Champlain’s drawings of Algonquian dress include light-weight basketry armor worn by Saco warriors on coast of southern Maine. According to Champlain’s key, these sktetches show warrior and trader or trapper dress on the left and casual and ceremonial wear on the right.

Champlain’s drawings of Algonquian Dress

Wigwams

William Wood wrote about the women gathering rushes in summer to make mats for their wigwams, which he describes as:[32]

[Very] strong and handsome, covered with close-wrought mats of their owne weaving, which deny entrance to any drop of raine, though it come both fierce and long, neither can the piercing North winde find a crannie, through which he can conveigh his cooling breath, they be warmer than our English houses.

Eastern Woodland people in New England used saplings and cordage to fashion the shelters we know familiarly as wigwams.[33] Middle and Late Woodland people lived in both informal and planned communities in wigwams on terraces or ridge lines above the flood plains of rivers, sometimes with demarcated tracts for communal planting and drying racks of meat and fish, and sometimes palisaded against possible enemy attack. Settlements were laid out according to the cardinal directions. In inland winter villages, wigwams were arranged in an open circle with doorways facing east, where the sun would rise at the vernal equinox, a time in late March when day (light) and night (darkness) last an equal number of hours, an augury of spring. In summer settlements along the shore, wigwams were more spread out and faced southwest, where the sun lingered longest on shortening days at the end of the growing season. Each wigwam had its own attached family corn patch and kitchen garden, sometimes fenced against animals, as seen on Champlain’s famous map of Le Beauport.[34]

In Maine, Canada, and the Merrimack Valley, Late Woodland houses were northern style, constructed of the same materials—saplings and bark—but pointed, shaped more like tepees. In New England and the Great Lakes region, wigwams were southern style, dome-shaped rather than pointed, and smaller, often only 8 to 10 feet in diameter. The frames were built by women with the assistance of men and boys, covered with shaped tree bark in winter and thatch or woven mats in summer, and secured with strips of ash pith or rope. A smoke hole over the apex vented the hearth, a stone-lined pit in the center.

Wigwams were for nuclear families as sleeping quarters, as many as ten people, but the structures could be joined together or larger ones built as needed to house larger extended families, like the longhouses of the other Woodland people to the west. In the southeast, Woodland houses were shaped more like quonset huts–quonset is an Algonquian word—a style similar to the longhouses of the Iroquoian peoples. A diversity of wigwam styles is found in New England archaeology. Whatever style was used, construction nevertheless reflected knowledge of structural engineering, materials science, and symmetry. Wigwams were knowledgeably engineered and constructed to manage instability, stress, capacity, and load, with the position and depth of postholes signifying the height and circumference of the structure. In archaeological sites, evidence of postholes is preserved in the earth as darker circular patches where the wood has decomposed in place, contrasting in color and texture from the surrounding soil.

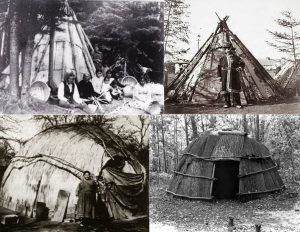

New England wigwam styles[35]

Francis Higginson, writing in 1629 in Salem Village (an area encompassing present-day Beverly, Salem, Peabody, and Danvers), provided this description of wigwams:[36]

Their Houses are verie little and homely, being made with small Poles pricked into the ground, and so bended and fastned at the tops, and on the sides they are matted with Boughes, and covered on the Roofe with Sedge and old Mats, and for their beds that they take their rest on, they have a Mat.

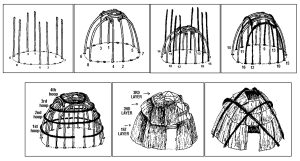

Wigwam construction began by scribing an even circle on the ground and marking locations for poles. Depending on the desired size, the diameter or radius for a wigwam could have been measured by the full length of a man with arms outstretched. The placement of poles involved positioning two poles on either side of the center point of each quadrant for each of the four cardinal directions, and then filling in the spaces with other poles. A 16-pole frame was standard, starting with pairs of saplings about 100 centimeters apart facing the four cardinal directions and then adding another pair of saplings in each of the intervals.

Both wigwams and whole villages were carefully laid out along north-south and east-west axes. Winter homes were larger and sturdier, but wigwams were intended as only temporary shelters to be abandoned, rebuilt, enlarged, downsized, or embellished as needed or desired.[37] The failure to build permanent architectural structures counted against them in the eyes of colonists, who did not understand how adaptive wigwams were for seasonal subsistence patterns and mobile farming. In addition to foodstuffs, materials for wigwam building and repairing—poles, bark, thatch, cordage—were cached in dispersed settlement areas for ready future access, another adaptation to a mobile mixed economy.

Wigwam construction process[38]

In 1674 Daniel Gookin recorded his observations of how wigwams were made:[39]

Their houses, or wigwams, are built with small poles fixed in the ground, bent and fastened together with barks of trees, oval or arborwise on the top. The best sort of their houses are covered very neatly, tight, and warm with the bark of trees, stripped from their bodies at such seasons when the sap is up; and made into great flakes with pressures of weighty timbers, when they are green; and so becoming dry, they will retain a form suitable for the use they prepare them for. The meaner sort of wigwams are covered with mats they make of a kind of bulrush, which are also indifferent tight and warm, but not so good as the former.

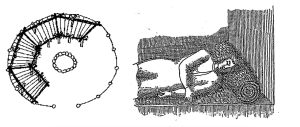

Inside the wigwam, before adding the shaped oak or chestnut bark skin, the people built sleeping platforms about 18 inches off the ground around part of the circumference. The platform provided seating with under-seat storage. At night the people spread cedar boughs or unrolled woven mats and furs on the platform to serve as a mattress and bedding. Heated rocks from the hearth could be rolled into troughs under the platform to serve as winter bedwarmers. According to Champlain:[40]

Their dwellings are separate from each other, according to the land which each one occupies. They are large, of a circular shape, and covered with thatch made of grasses or the husks of Indian corn. They are furnished only with a bed or two, raised a foot from the ground, made of a number of little pieces of wood pressed against each other, on which they arrange a reed mat, after the Spanish style, which is a kind of matting two or three fingers thick: on these they sleep….

In their wigwams, they make a kind of couch or mattresses, firm and strong, raised about a foot high from the earth; first covered with boards that they split out of trees; and upon the boards they spread mats generally, and sometimes bear skins and deer skins. These are large enough for three or four persons to lodge upon: and one may either draw nearer or keep at a more distance from the heat of the fire, as they please; for their mattresses are six or eight feet broad.[41]

Sleeping Platforms in Wigwams

William Wood’s 1634 sketch of a sleeping platform shows an Englishman reclining on a woven fiber bedroll. Wigwam embellishments and interiors were the province of women and girls, who covered the frames inside and out and wove the mats for bedding and seating at mealtimes and meetings. Diplomacy was conducted on large mats. Fibers from the stalks of nettles and milkweed were used to make warp string for weaving the mats. Women used the string to sew cattail leaves into insulation liners for winter wigwams. The people also shaped cattail leaves and corn husks into children’s toys and duck hunters’ decoys. The soft, absorbent fluff from burst cattails was used to insulate moccasins in winter and packed into cradleboards as easily replaced diapering material. Bast fibers inside cattails and the stalks of other plants were used to make strong twine, fishing line, and bowstrings. These plants still grow in Essex County, if less abundantly. Milkweed meadows have fallen victim to housing development, and invasive species such as phragmites are rapidly replacing the few remaining stands of cattails.

Late Woodland people made perfect wigwams without the use of formal mathematics or geometry or a written numerical system. For counting they used gestures and words referring to fingers and hands, using a base-5 system. In linguistics this is referred to as a quinary system. The word for six, for example, meant “first on the other hand” (one hand plus the baby finger on the other), seven meant “second on the other hand”, and so on. Counting was done from left to right on the left hand first (facing out), then left to right on the right hand. Gesturally, six could be expressed as a closed left-hand fist with a closed thumb on the right hand, or an open hand on the left with a raised baby finger on the right.[42]

The base-5 finger-hand (and then toe-foot) system thus was flexible or convertible in the same sense that 10 pennies, two nickels, and a dime all mean “ten cents”. Six could also be expressed in a word for “three on each side”, for example, and eight could be “four on each side”, but four could also be expressed as “two twice”; that is, gesturally, four could be the fourth and fifth (baby) fingers of the left hand (fingers “1” and “2”), closed (or bent down), with the hand pushed forward or pumped two times (the two, twice). Sixteen was three hands, or fists (5 + 5 + 5) plus one (or two hands and a foot plus one toe).

Counting went as high as 1,000, or “great 100”. In Abenaki, the word for 1,000 was “one box”, with its figurative rather than literal meaning derived from context. In picture writing and petroglyphs, boxes are thought to have represented multiples of 100 of whatever was being counted. Words for numbers often varied according to their classifiers. For example, there might be entirely different words with a similar numerical prefix for “3 people”, “3 things”, “3 times”, “3 places”, or “3 ways”. Times could be represented as sun risings or settings, lunar cycles or “moons”, or lifetimes.

Canoes

Thus, more than any other raw material, wood products, plant fibers, and tree resins were the mainstay of Eastern Woodland domestic technologies. Another prime example is the construction of canoes. According to William Wood (1629):[43]

[They] crosse these rivers with small Cannowes, which are made of whole pine trees, being about two foot & a half over and 20 foote long: in these likewise they goe a fowling, sometimes two leagues to sea.…

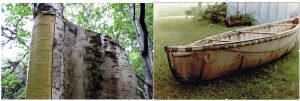

Harvesting and building with birchbark

Men also wrapped trunk-lengths of birch bark (preferably yellow or paper birch in one long piece) over wood frames (ash) and sealed the ends. Struts secured the shape at the widths. Rope and pine pitch held bark to frame and made the vessel watertight. Birchbark canoes were used mostly for lake and river travel, while dugout canoes in oak and pine were made for heavy-duty uses that did not require portages, such as inshore, estuary, and deep-sea fishing. Heavy reliance on all-purpose canoe travel led ethnologists to refer to the Eastern Woodland Indians as a “canoe culture”.

Birchbark canoes in the Penobscot Museum, Indian Island, Maine [44]

The Eastern Woodland Indians occupying New England and much of the Northeast before and during the Contact Period are known as the Eastern Algonquians, members of a language family. As with the Indo-European language family, the diverse members of the Algonquian language family shared a common ancestral language in the deep past. As a result they shared many aspects of a common culture, as well as common technological adaptations, because language and culture are deeply intertwined.[45] And this leads me to my next question: Who were the Algonquians, and how they make their living in Essex County?

Return to What people lived in Essex County, and when?

Notes and References

[1] My principal primary source for the information about Algonquian material culture is Daniel Gookin’s Historical collections of the Indians of New England (written in 1674 and first published in 1692. See http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/sc_pubs/13/). Other than Gookin, the best source on Pennacook/Pawtucket technologies and subsistence activities is Chandler Potter’s History of Manchester (NH), 1856, especially pp. 32-50, in which he relates the direct observations of Roger Williams (A Key into the Language of America, 1643) and John Josselyn (An Account of Two Voyages to New-England, 1634), in addition to Daniel Gookin. A convenient source for primary accounts is Ronald Karr, ed. (1999), Indian New England 1524-1674: a compendium of eyewitness accounts of Native American life. A classic local source is Charles Willoughby’s comprehensive Antiquities of the New England Indians (Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, 1935). Standard ethnological accounts of Native technologies based on primary sources include Volume 1 of the Smithsonian’s Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Frederick Hodge, ed. 1907), and Volume 15, Northeast, in the Smithsonian’s Handbook of North American Indians (Bruce Trigger, ed. 1978: http://anthropology.si.edu/handbook.htm).

[2] As noted in the section on the Maritime Archaic people, archaeologists do not all agree on the extent to which they developed woodland technologies in situ in New England, with or without outside influence, and the extent to which the new technologies were imported through the migration of people from the Mississippi, Ohio, Ottawa, and Susquehanna valleys from the west. Certainly, corn was introduced from the west. Whatever may have developed in situ, I am persuaded that the presence of burial mounds and Adena- and Hopewell-style projectile points in Early and Middle Woodland sites in New England (including the Susquehanna and Point Peninsula styles) reflects direct influence from carriers of those cultures.

[3] Because archaeologists specialize, general sources on the Woodland Period and Eastern Woodland Indians are rare, other than books for children. Online lecture notes for introductory college courses on the subject are useful. My preferred primary sources on Native life in the Late Woodland Period as reflected in Contact Period contexts include Thomas Hariot (1585), John White (1585), Samuel de Champlain (1604-1610 [Otis Vol. II 1878]), Edward Winslow (1624), William Wood (1634), Thomas Morton (1637), Roger Williams (1643), Edward Johnson (1654), John Josselyn (1674), and (Daniel Gookin (1674). Kathleen Bragdon’s book Native People of Southern New England 1500-1650 (1999a) is a good secondary source for the Late Woodland and Contact periods.

[4] These Cape Ann sites are known from both archaeological and documentary evidence. For example, Wingaersheek is known from an early English account, reported in John Babson’s history (1860) and in N. True’s 1868 analysis of Algonquian place names, and from the excavation of the Contact Period Matz site at Wingaersheek beach (Keller 1965). Sites in Riverview, Riverdale, and the Annisquam River Islands are known from John Dunton’s memoir (1686), Ebenezer Pool’s account (1823), site reports filed in the 1920s by Frank Speck and Frederick Johnson at the R. S. Peabody Museum in Andover, and excavations conducted in the 1930s by N. Carleton Phillips. A Pawtucket settlement above Old Garden Beach is the source of the Old Garden Cove place name on the earliest maps of Sandy Bay (Mason 1831), and a Late Woodland settlement is corroborated by horticultural artifacts collected there by Marshall Saville (1920) and donated to the Sandy Bay Historical Society. A similar pattern of discovery applies to the other sites: evidence of a Late Woodland native settlement at Lobster Cove, including the Annisquam Effigy (Willoughby 1935); preserved corn hills discovered behind dunes on Coffin’s Beach (Phillips 1940), an old newspaper account of Indians visiting their traditional homeland on Andrews Point, Champlain’s account of the Indians in Fishermen’s Field, Ipswich colonists’ accounts of Indians at Chebacco and Argilla Road, and so on.

[5] See Brothers among Nations: The pursuit of intercultural alliances in early America, 1580-1660 (Van Zandt, 2008). For more information on the commodities of Native American trade, see “Indigenous Trade: The Northeast.” American Eras. 1997. Encyclopedia.com. 19 Mar. 2015, at http://www.encyclopedia.com.

[6] Principal sources for the identification of artifacts in this chart and throughout this book are the Boudreau (2016) and the Fowler (1991), also William Ritchie’s 1970 Typology and Nomenclature for New York Projectile Points. Examples of technical reports on artifacts are Robert Goodby’s article on Jack’s Reef Points (2013) and William Hadlock’s articles on platform pipes (1947). See also Charles Walcott’s 1954 article: Locally available stones: First choice for artifact manufacture (Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 15). All the artifacts shown are from Rockport, Gloucester, Essex, Ipswich, or other communities in Essex County. The words in italics identify the items shown.

[7] Clockwise from top left: perforated paint stones, corn abrader, groved club head, projectile points, polished celt, high-sided deerhide scraper.

[8] In a talk at the Gloucester Rotary Club in 1940, N. Carleton Phillips presented 23 samples of the hundreds of pieces of pottery he took from sites in Riverview (Gloucester Daily Times, November 13, 1940, Cape Ann Rich in Indian Relics Rotarians Told).

[9] Champlain reported in Voyages II (p. 74), “When they eat Indian corn, they boil it in earthen pots, which they make in a way different from ours.” In Le grand voyage au pays des Hurons (1632), Garbiel Sagard, a French fiar with the Wendat (Wyandot, aka Huron) described the Eastern Woodland manner of manufacturing pottery, carried on exclusively by the women. There is a 1939 English translation, as Sagard’s long journey to the country of the Hurons, by George M. Wrong (The Champlain Society). The examples of decorative styles in the photo are from Ipswich, in the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA (M.E. Lepionka photos).

[10] The classic source on Algonquian pottery in New England is Willilam J. Howes (1943), Aboriginal New England Pottery, in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 5(1). A good contemporary source is Lucianne Lavin (1997), Diversity in Southern New England Ceramics, Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut 60: 83-95.

[11] Information about clay is given in Fullerton et al. (2003) USGS Map of Superficial Deposits and materials in Eastern and Central United States, at http://pubs.usgs.gov/imap/i-2789/i-2789_p.pdf. A more local source is Allen et al. (1960) Clays and Clay Minerals in New England and Eastern Canada in the Geological Society of America Bulletin 71(1).

[12] John White’s watercolor shows bulk cooking in a heavy duty clay pot in Virginia in 1585 (“the seething of their meat in pots of earth”). Gookin cites Williams and Josselyn on cooking in animal bladders versus pots and baking fish encased in clay, as well as the clambake; e.g., Josselyn p. 109. As an alternative to bringing liquid to a boil by placing clay pots directly on a fire, the same result was obtained by dropping fire-heated rocks into the liquid and swapping them our for hotter rocks as they cooled. As an alternative to steaming fish in a pot, they would completely encase a fish in wet clay and lay it on the fire. The fish—a salmon, mackerel, bluefish, or striped bass—was done when the clay was baked hard. Breaking and peeling off the clay effectively cleaned the fish, as the scales would stick to the clay. They served the top filet first, then removed the backbone–to save to dry and powder for use in flavoring soups, and then ate the bottom filet. Nothing was wasted. The clay was crushed for reuse as temper in ceramics.

[13] A traditional classification of ceramic styles is given in William Fowler’s 1960 Ceramic Development Stages with Some Contemporaneous Lithic Traits in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, 22(1). However, classifications of ceramic types and styles frequently undergo revision, as pottery in New England was very diverse and different styles often were contemporaneous in the same populations. The trend has been to pay more attention to the functionality and uses of ceramics in relation to subsistence activities rather than to formal classifications based on styles. See especially Elizabeth Chilton’s 1999 Ceramic Research in New England: Breaking the Typological Mold, in Levine et al., The Archaeological Northeast. See also Jonathen Lizee’s 1994 paper, Cross-Mending Northeastern Ceramic Typologies at http://archnet.asu.edu/archives/ceramic/exchange/exchange.html. See also my article on the subject, Ancient Pottery from Cape Ann, Essex, and Ipswich Massachusetts, in the 2018 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 79(2): 64-74.

[14] The use of clay for waterproofing and in cache pits is described in Howard Russell (1962), How aboriginal planters stored food, in Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 23 (3,4). Karine Tache described the use of clay in baking in her talk, Pots, People and Fish in the Early Woodland at the November 2, 2013 Eastern States Archaeological Federation 2013 Annual Meeting, South Portland, Maine.

[15] Pots with pointed bottoms were for propping on rocks in the hearth or in sand, while pots with flatter bottoms likely were used to store food in cache pits. Darker-colored pots were fired in more closed oven-like conditions, while pots lighter in color were fired in open air fire pits, exposed to more oxygen. The thickness of the walls and the type and amount of temper used–fibers, quartz, mica, grit–affected the strength, and therefore the use, of the pot.

[16] These rare examples of fabric remains from Manchester-by-the-Sea are in the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Their status as possible burial remains has not been determined, but it was customary in the 19th and early 20th centuries for human remains and grave goods from Indigenous burials to be sent to universities for forensic anaysis and museum collections. Multiple exhumations from Adams Hill in Annisquam, Choate Island in Essex Bay, and Indian Ridge in Ipswich were sent to Harvard, for example. The earliest colonial burial grounds in New England overlie or extend from Indian burial grounds.

[17] Clockwise from top left: canoe and snowshoes (Penobscot Museum, Indian Island, Maine), cradleboard, woven cattail mat, eel trap, woven basket, wooden spoons, decorated bark basket.

[18] The story of using live wood to haft a stone tool or weapon, originally from Roger Williams, is also quoted on p. 39 of the C.E. Potter.

[19] In the primary source document, moose was written moofe or moufe in 17th century orthography, confusing the word with mouse, also written as moufe. Later accounts repeatedly copy this reference as the “shoulder-blade of of a mouse”. However, the scapula of even a very large mouse would never have served as the business end of a garden hoe or fireplace shovel. In New-Englands Prospect William Wood (p. 107) saw moose and deer antlers hafted in a similar fashion to serve as clamming forks. For a perspective on the importance of Native technologies involving the use of wood and fibers, see William S. Fowler (1962), Woodworking: An important industry, in Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 23 (3, 4): 29-40.

[20] This remnant of a hafted moose-scapula shovel was used to scoop charcoal and hot rocks from the hearth. N. Carleton Phillips made the reproduction of the hafted axe in the picture, which he exhibited to Gloucester Rotarians in 1940 (See Lepionka 2013, Unpublished Papers on Cape Ann Prehistory).

[21] Dogbane (hemp), bulrushes, cattails, milkweed, and nettles—containing the fibers that women gathered and twisted to make S-warp string and fishing line—still grow on Cape Ann, if less abundantly. Milkweed meadows have fallen victim to housing development, and invasive species such as Phragmites are rapidly replacing the few remaining stands of cattails. Thomas Morton, William Josselyn, and John Winthrop are the principal primary sources on native plants in New England in the 17th century. Milkweed, cattail, dogbane, and other New England species used by the Eastern Woodland Indians are also described in Charles Pickering’s 1879 Chronological History of Plants. A comprehensive list of Cape Ann plants and shrubs, compiled by the Annisquam naturalist Elliott C. Rogers (Botanist’s Eye View of Dogtown Flora), appears in the August 27, 1954 of the Gloucester Daily Times.

[22] Champlain describes Indian Hemp in Chapter 3 of Volume 1 (1567-1635, the Slafter edition). See also Thomas Morton, p. 46.

[23] Wood, pp. 100-101; see also his description of basketry on pp. 107-108. Another description of Algonquian baskets is in William James De Forest, The History of the Indians of Connecticut (1853), p. 13.

[24] This “spinning stone” or spindle whorl is from Coles Island in West Gloucester, and likely was used in the production of fishing line and string for nets. It is in the private collection of Tom Ellis of West Gloucester.

[25] These palm tools for weaving came from Plum Cove in Gloucester, the Chadwick Collection from Cape Ann in Middleborough, and Tom Ellis’s collection from West Gloucester.

[26] These examples of weaving are from William Henry Holmes’ classic work, Prehistoric Textile Art of Eastern United States (1866), available as a Gutenberg e-book (#19921). For more on Woodland Period weaving see http://www.woodlandindianedu.com/textileandfiberarts.html.

[27] Of the plants favored for basketry, sweetgrass still grows abundantly on Cape Ann, while beach grass and eelgrass are endangered, mainly due to climate change. The botanist Ralph Dexter came to Cape Ann to study eelgrass in the 1930s and went on ethnological expeditions with Frank Speck from Speck’s summer base at Riverview. Dexter and Speck co-published scientific papers on marine plant and animal use by the Wampanoag, Micmac, and Malecite (see Grieger 2002).

[28] Prime plants for basket weaving in coastal New England included sweetgrass (Hierochloe), beachgrass (Ammophila), and eelgrass (Zostera).

[29] Information on making coiled grass baskets comes from Tara Prindle’s NativeTech web site. See http://www.nativetech.org/basketry/index.html.

[30] Information on natural vegetable dyes in New England comes from the NativeTech web site. See also Richards and Tyri, Dyes from American Native Plants (2005).

[31] These articles of clothing are in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian and were collected in New England during the Contact Period.

[32] William Wood, New England’s Prospect (1634), p. 106.

[33] Wampanoag people refer to them as wetus.

[34] Information on Algonquian villages comes from Champlain (Volume I, Chapter II, Summer 1604), William Bradford and Edward Winslow (1624), and Gookin (e.g., pp. 9-10). Other examples of settlements are in White’s Algonkian Watercolors are at http://pointersquest.blogspot.com/2009_12_01_archive.html. Champlain’s map of Le Beauport showing a summer settlement on Gloucester Harbor was presented in a previous section.

[35] Three of the historical photographs are from the Library of Congress archives, of Abenaki and Penobscot pointed bark wigwams and a large Ojibwe wigwam, dome-shaped and matted. The fourth (lower right) is a reproduction of a comparatively small dome-shaped wigwam of the Massachuset. The first English colonists copied this style of wigwam construction—elongating it and adding a rectangular doorway at one end and a stone chimney at the other—for their earliest housing, until 1640, when the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony declared that Englishmen should not be living in wigwams but should build proper English homes.

[36] Francis Higginson (1629) was writing from Salem Village in Naumkeag; see New England’s Plantation: A Short and True Description of the Commodities and Discommodities of that Country, reproduced without pagination at http://www.winthropsociety.com/doc_higgin.php.

[37] Gookin (pp. 9-10, 147-152), Wood (pp. 105-106), and others describe the differences between winter and summer wigwams and were either admiring or disparaging of them. All were astonished at how casually wigwams were erected and destroyed and how the Indians made no effort to construct permanent homes. Algonquian living arrangements merely reflected the realities of seasonal migration, but colonists saw the lack of permanent architecture, permanent wealth, and permanent residence as a sign of cultural inferiority.

[38] The diagrams of wigwam construction come from Tara Prindle’s 1994-2015 NativeTech web site at http://www.nativetech.org/wigwam/construction.html. NativeTech features many other pages on other Algonquian technologies as well.

[39] Gookin, pp. 9-10.

[40] Champlain (Volume I Chapter II—July 1603). Champlain also describes woven mats (and fleas) in Chapter XIV—September 1604—of the Gutenberg edition of the Otis translation). He writes, “They have a great many fleas in summer, even in the fields. One day as we went out walking, we were beset by so many of them that we were obliged to change our clothes.” According to Gookin, Dutch traders and French missionaries also complained of fleas. Josselyn notes that the Indians slept with their dogs. Whenever flea infestations became intolerable, the people just tore down their houses and erected new ones some distance away. Interestingly, Roger Conant mentions in a letter to John White that the wigwams in Fishermen’s Field were flea-infested, prompting the would-be settlers to attempt to construct their own for the winter of 1625 (see Frederick Conant’s 1877 biography of Roger Conant and Frances Rose-Troup’s 1930 biography of the Rev. John White).

[41] Champlain, pp. 124-125 of the Slafter edition. Other sources on sleeping arrangements are Roger Williams (p. 45), Thomas Morton (pp. 19-20), and Daniel Gookin (p. 152).

[42] My sources on the Algonquian counting system include Roger Williams (1643), Frederick Hodge (1906), Michael Closs (1986), and Rudes and Cosa (2003).

[43] Wood, p. 48. Gookin also describes canoe-making (pp. 152-153). Frank Speck built Algonquian birchbark canoes in Riverview, Gloucester, and paddled them in the Annisquam River. According to Speck’s papers in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, one of his correspondents on canoes and Algonquian languages was Edwin Tappan Adney of New Brunswick, Canada, whose book Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America has recently been reissued. Another good secondary source on the subject is William Haviland, Canoe Indians of Down East Maine (2012).

[44] These vintage birchbark canoes are in the Penobscot Museum on Indian Island in Maine. (M.E. Lepionka photo).

[45] For a perspective on tracing people’s origins using linguistic approaches, see Stuart Fiedel’s articles, Algonquian Origins: A Problem in Archaeological-Linguistic Correlation, in Archaeology of Eastern North America 15 (Fall 1987), and Are Ancestors of contact period ethnic groups recognizable in the archaeological record of the early Late Woodland? (2013), in Archaeology of Eastern North America 41.