The loss of Indigenous history on Cape Ann has been caused partly by casual collectors, looters, commercial and residential developers, and even by archaeologists themselves. Collectors and looters, focusing solely on objects, often have removed evidence from physical contexts that might have led to real discoveries in reconstructing the history of intact sites. Also, without documentation, both provenance (tracing possession of a find) and provenience (identifying the location of a site) are lost. The purpose of archaeology as a historical method–to reconstruct past events from unwritten evidence–is thwarted. Additionally, comparatively little archaeology has been done here. Beginning in colonial times potential sites have been overlain by municipal, private residential, and industrial development. The most likely site of the Pawtucket village of “Wenesquawam” (Wonasquam, Wanaskwiwam), for example, is now under a mid-20th century housing development between Riverview Road and Corliss St. in Gloucester. An unmarked small public park called Brown’s Field on Wheeler Street abutting a small spring-fed pond is all that remains of it.

Little modern archaeology has been done here.

Archaeology on Cape Ann is complicated by environmental factors as well. Sites tend to have been repeatedly covered up and exposed and re-covered by glacial action, dune migration, flooding, wind erosion, and wave action. These actions mix up the stratigraphy or layers of cultural and geological deposits, making site discovery and interpretation difficult. In addition, as a result of mega-environmental changes, many ancient sites are now underwater in coves and at river outlets, under ponds created by the damming of rivers and diversion of streams, and under protected barrier beaches and dunes, salt marshes, and wetlands. Today, the best chances for rediscovering Cape Ann’s pre-Contact past is on city properties, public lands, protected areas along waterways, drained wetlands, conservation lands, and sea floors.

Historical factors in the sciences also play a role. On most archaeological maps of New England, Cape Ann is blank, largely through a lack of professional interest in the area. Many sites in coastal New England have low densities of artifacts because they were occupied only seasonally. As a consequence, archaeologists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came to regard New England as uninteresting, offering little more than shell heaps and burials.[1] The shell heaps and burials were promptly dug up, with grave goods going to museum exhibits and bones and skulls to physical anthropologists for forensic study.[2] On Cape Ann and vicinity, for example, Indigenous burials, first reported in 1837,[3] were removed from Adams Hill and Norwood Heights in Annisquam, land bordering the Seaside Cemetery in Lanesville, land along School street overlooking Manchester Harbor, the crest of Choate (Hog) Island in Essex Bay, and land along Argilla Road in Ipswich.

Archaeologists preferred to build their careers on expeditions to exotic sites in the Ohio or Mexican valleys with richer material cultures and monumental architectures. For a hundred years, largely through convention, anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians tended to deny the status of “civilization” to Indigenous Peoples of North America because they lacked the ziggurats, monumental sculpture, astronomical calendars, writing systems, extensive social stratification, and accumulations of permanent wealth such as gold, etc., of the aboriginal people of Mexico and Central and South America. Only recently has interest developed in the importance of New England to understanding the history of human migration, patterns of settlement in the Americas, and Indigenous life during the early Contact and Colonial periods.

Erasure narratives have misled us.

But the most important reason we know so little about Native history here is a continuing denial of Indigenous existence. Many local histories, such as John Babson’s 1860 history of Gloucester, do not even mention “Indians”. Loss of early town records to catastrophic fires is sometimes given as a reason that indigenous people have been largely left out of historical accounts, but the real reason lies in a process known as “Erasure”. Erasure refers to the intentional falsification, redaction, or loss of records of the past. It happens all the time in the politics of the archives and in every generation—such that the work of the historian is never done. Erasure may be defined as the modification or distortion of the historical record to downplay or highlight selected events, or remove facts that people are not proud of, are prejudiced against, or wish to conceal as politically incorrect or illegal. The claim that “the Indians” had no civilization and mysteriously disappeared prior to English settlement is a prime example.[4]

Most New England town histories and centennial addresses of town fathers dismiss the subject of “Indians” except in reference to deeds, accusations of mischief, uprisings or fears thereof, wars, laws, and court cases. Obadiah Bruen’s 1650 record of the founding of Gloucester and John Wingate Thornton’s 1854 history of the founding of Gloucester do not mention “Indians”, for example.[5] Based on such omissions, we have been told there were no Indigenous people on Cape Ann when the English came. They had become extinct through disease and warfare or had abandoned the area. In any case, the argument goes, they were mere wanderers with no permanent settlements.

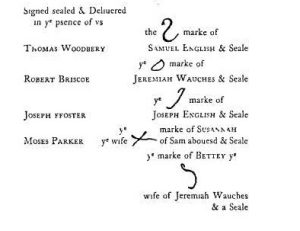

“History” begins with the quitclaim deeds to Native homelands on which the colonists’ established their plantations, including the deed to Beverly, Gloucester inclusive of Rockport and Essex, and other towns in Essex County, signed by the grandchildren of the Pawtucket sagamore, Masconomet (Masquenominet).[6]

Erasure Narratives

- They are extinct and only a few stones and graves show they ever existed.

- Nothing is known of them as they kept no records of their past.

- They belonged to the wilderness and never lived in any one place.

- We had friendly intentions, but they had already died out from disease.

- They had already killed each other off through internecine warfare.

The narratives of erasure appear in D. F. Lamson’s 1895 history of Manchester-by-the-Sea, which dismisses indigenous people in this single opening paragraph:

The history of America begins with the advent of Europeans in the New World. The Red Men in small and scattered bands roamed the stately forests and interminable prairies, hunted the bison and the deer, fished the lakes and streams, gathered around the council-fire and danced the war-dance; but they planted no states, founded no cities, established no manufactures, engaged in no commerce, cultivated no arts, built up no civilizations. They left their names upon mountains and rivers…but they made no other impress upon the continent which from time immemorial had been their dwelling place. The record of their past vanishes like one of their own forays into the wilderness. Their shell heaps and their graves are the only remains left to show that they once called these lands their own. They made no history.[7]

The implied contrast is clear:

| “INDIANS” OF NEW ENGLAND | THE ENGLISH IN NEW ENGLAND |

| Made no history. | Made history. |

| Were mere wanderers. | Established permanent settlements. |

| Disappeared naturally into the Wilderness. | Tamed the Wilderness. |

| Were unable to become civilized. | Planted Western civilization. |

| Were unable to become modern. | Practiced modernity. |

| Had no future. | Had a bright future. |

| Were the last of their kind in a doomed world. | Were the first of their kind in a New World. |

The Disappeared

John J. Currier’s 1896 History of Ould Newbury and John R. Pringle’s 1895 History of Gloucester say essentially the same thing. According to Pringle, the “disappearance” of the Indians from Cape Ann was a big mystery. He suggests Indians deserted the area rather than being driven out or otherwise discouraged from living here.[8]

When the first settlers came…in 1623, to set up a fishing stage in what is now Gloucester, there were few traces of savages, and but little evidence of Indian occupation. Whether pestilence or other causes led to their final desertion is a matter of speculation. The only evidences of their occupancy were found on the northerly side of the Cape, where great heaps of clam shells attested their former presence. The town was thus spared from the terrors of Indian warfare, so common an experience with the early settlers in other sections.[9]

James R. Pringle is at the bottom center of this brochure page identifying producers of Gloucester’s 250th anniversary celebration in 1892. Pringle designed historical floats for the occasion, including one commemorating the signing of the Indian deed to Gloucester.

The “pestilence” argument, based on accounts of indigenous populations being decimated by epidemics of virgin soil diseases (i.e., introduced diseases for which people lacked immunity), was uninformed of the fact that by the end of seventeenth century Indigenous populations were recovering through acquired immunity.[10]

The leptospirosis epidemic of 1600-1620 and the smallpox epidemic that reached Essex County in 1633 are taken up in greater detail in another context. While devastating, these events in no way led to the extinction of coastal Indigenous Peoples in southern New England. The extinction narrative was based on the dramatic fatalities on the South Shore recorded by John Winthrop, William Bradford, and other observers, which were later assumed to apply to all Native communities everywhere. By the end of the nineteenth century Currier, Babson, Pringle, and others were simply repeating earlier claims of disappearance or omitting Indigenous history altogether.

Dissenting views, such as Joseph Felt’s, were discarded. In his 1845 History of Salem Felt asserts that earlier histories must be incorrect in claiming that the Indians were extinct prior to the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, because there are so many accounts of them. He questions why there is no word on what happened to them, and notes that collectors found “Indian Town” full of bones, and up to 1725 Indians visited Salem every summer and camped on Gallows Hill. End of story. (Gallows Hill is where Salem hanged its witches, and there is no record of how it became a pilgrimage destination for the Pawtucket.) Joseph Felt was regarded as an “Indian lover” in his time, and even today archivists with inherited views will still suggest that he be taken with a grain of salt.[11] Tourist brochures in Salem today guide visitors to a reproduction of a colonial Pioneer Village (complete with a wigwam suggesting erroneously–Plimoth Plantation likewise–that colonists and Indians lived together), but there is no mention of any “Indian Town”.

In his 1905 History of Ipswich, Thomas Waters says that Indian history is a great mystery, but while it cannot be known, it should not be ignored:

The long, simple, uneventful ages of the wilderness period that ended when the white man came, must ever remain too dim, shadowy and ghost-like to be subjected to the historian’s rigid method. But a fine sense of justice to the unnumbered generations of Indian men and women, that preceded our own ancestors in ownership, as truly men and women as ourselves, however rude or cruel, compels us not to ignore their unrecorded history, but to construct it as best we can.[12]

However, Waters goes on to claim that Indians practiced cannibalism on Treadwell (Perkins) Island (in the Ipswich River in South Hamilton). Residents had actually discovered a bundle of bones in a stone chamber, a type of burial from the Early Woodland period known as an ossuary. In most other respects Waters’ account closely resembles Pringle’s.

The phenomenon of Erasure is by no means unique to Cape Ann but has been observed in other New England communities.

Abenaki in coastal Maine:

The widespread acceptance of permanent Indian emigration from these areas in both historical literature and popular myth resulted from what appeared to be compelling evidence. However, there is overwhelming evidence that many Abenakis remained in western Maine until the end of the century, and some descendants still inhabit the area today. Their “disappearance” from history resulted more from the ethnocentric views of colonial observers and the misunderstandings of early historians than from an absence of Indian inhabitants.[13]

Massachuset and Wampanoag in Boston Bay and the South Shore:

As they successfully dispossessed and displaced Indians, the heirs of English colonialism seized the power to define the rules governing the social order, and they constructed New England Indians as peculiar and marginal. Local historians underscored the “disappearance” of the Indian population by singling out individuals…as representing he “last survivor” of their “tribe”.[14]

Nipmuc in Worcester County:

[T]he disappearance model became an official story, erasing Massachusetts Indians from local history. Far from disappeared, however, Natives of central Massachusetts in the nineteenth century were farmers, plumbers, washerwomen, mariners, chair caners, Indian herb doctors, barbers, shoemakers, domestic servants, baggage masters, itinerant entertainers, day laborers, railroad engineers, mill operatives, specialty bakers, broom and basket makers, housewives, stage coach drivers, and church deacons.[15]

Firsting and Lasting

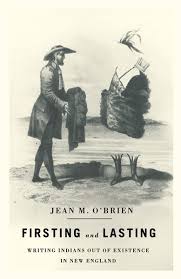

Jean O’Brien coined the phrase “firsting and lasting” for historical texts that focus on “firsts” achieved by the English and that either celebrate or lament “the last” of the Indians. The subtitle of her book is Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. Her book cover shows Poquanum, known as Black Will, selling Nahant to Thomas Dexter for a suit of clothes in 1628. In the image, the Indian has become invisible, leaving only the clothes.[16]

Jean O’Brien coined the phrase “firsting and lasting” for historical texts that focus on “firsts” achieved by the English and that either celebrate or lament “the last” of the Indians. The subtitle of her book is Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. Her book cover shows Poquanum, known as Black Will, selling Nahant to Thomas Dexter for a suit of clothes in 1628. In the image, the Indian has become invisible, leaving only the clothes.[16]

In fairness, there are reasons that early colonists may have gotten the impression that the Indians had “disappeared”. Coastal indigenous people in New England were organized as extended families or bands—voluntary associations that frequently changed in membership and size. Bands practiced seasonal migration to subsistence resource sites and simply constructed wigwams wherever needed, such that wigwams at any specific location could have been found unoccupied at certain times. Some families went inland to winter villages to focus on trapping and to cash in on spring fish runs before returning to their coastal wigwams in summer. Also, villages may have seemed abandoned when the people were only on trading or warfare expeditions or on religious or kinship pilgrimages. Pilgrimage to honor ancestors and spiritual places was an Algonquian tradition. Empty wigwams also may have been found during planting season, because agricultural settlements often were relocated to provide fresh soil for corn, a heavy nitrogen feeder that quickly depletes soil. The people did not carry wigwams from place to place but simply constructed them wherever they were and occupied them as needed.

Finally, Algonquians throughout the Northeast had a tradition of temporarily abandoning any site where any sickness, violence, unpleasantness, or unluckiness occurred. Traditionally, such events were attributable to harmful spirits inhabiting or attacking a place, which could be reoccupied only when the shaman said it was safe to do so. During the colonial period, such “bad-spirit” events arose through contact with the colonists. Even when avoiding spiritually harmful or dangerous places, however, Indigenous people were here throughout the colonial period. They periodically had to make themselves scarce, or invisible, but always came back whenever it was safe to do so. Some sought to assimilate; others came back seasonally during peaceable times, and some still visit traditional homelands and sacred sites here today.

In the process of being “disappeared”, Indigenous people were redefined as “other” and by the mid-1800s were presumed to no longer exist east of the Mississippi. Their otherness included the stereotypes of the “hostile Indian” and the putative “last Indian” and these are the memes our town histories preserved, to be retold ever since. In 1892, for example, William Cogswell spoke at a banquet on the occasion of the 250th Anniversary of the Town of Gloucester. He referred to the Indians as obstacles to the nation’s manifest destiny—the belief that United States expansion throughout the Americas was preordained and inevitable. Cogswell said:

This celebration means more than commercial prosperity and supremacy. It means, with the disadvantages of a hard climate, a sterile soil, and the hostile Indian, the overcoming of these obstacles, the breaking away from colonial dependence on Great Britain, and the successful establishment of a new country, then unconquered and unexplored, which today extends from ocean to ocean….[17]

And so on. It’s America’s Story. William Cogswell’s ancestor had been granted 300 acres in Essex in 1636, where he built the original version of the house museum that stands there today. Modern-day archaeological excavations have revealed a long and rich Indigenous history on that property, but brochures for Cogswell’s Grant refer only to colonial history.[18]

Skeletons in the Closet

Erasure was grounded in Anglo-European ethnocentrism and chauvinism. There had to be “founding fathers” with superior accomplishments and firsts to be proud of in the transfer of Western civilization to a new land. Prejudice against Indians paralleled the need for foundation myths and firsts. Prejudice arose from judgments of technological, economic, cultural, and moral inferiority: Native people did not fence their farmsteads, keep domestic animals, manure their fields, or practice metallurgy. They were not Christians, did not live in towns, did not read and write, and were “naked”.[19] Gradually, the “other” became racialized, with prejudice and discrimination based on judgments of racial inferiority, cloaked in the early twentieth-century’s infatuation with scientific racism and eugenics.

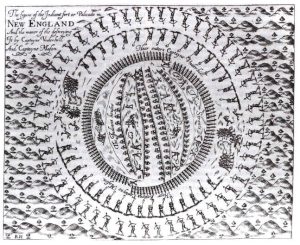

Accounts of colonists attempting to help the wandering aborigines enter the modern age of seventeenth-century Europe gave way to accounts of how they had to subdue or eradicate what was left of the Indians. The first seal of Massachusetts features a “naked” Indian with a caption bubble that reads, “Come over and help us”. The downward pointing arrow is a symbol of defeat, and the pine trees represent the source of colonial wealth from their first chief export from New England.[20]

Coming to New England to help Indigenous people at first included aggressive campaigns of Christianization, assimilation, protection in special “Praying Indian” towns on the frontiers, and, for a time, equal protection under English law. As replacing the Indians came to be seen as a natural, even divinely ordained, process, however, the idea of “helping” them radically changed. Thus, Erasure occurred also because there were skeletons in the closet, facts that if known might make us not so proud of our colonial ancestors. The truth is that after the first generation or two the colonists made the Native people unwelcome in their own land, discouraged them in every way possible, enslaved them, and dispossessed them of their livelihoods and lives.[21]

Taming the Wilderness

The view that the extinction of Indians was a natural consequence was linked with a “Wilderness” narrative, expressed even into the 20th century. Spencer Trotter writing in 1909 about forests in the Northeast, for example, asserted that Indians could not possibly aspire to civilization or modernity because of their dependence on wilderness.

[The] failure to advance culturally and increase numerically through intelligent use of the soil is the underlying fact in all backward peoples, and their backwardness is, in large measure, the result of environment…[with] overwhelming forests, unfertile tracts and fringe-lands. A non-agricultural people can not wrest a civilization of the wilderness.[22]

The Anglo-European construction of “Wilderness” was based on the belief that civilization is antithetical to it. Trotter even claimed that because Indians could not live apart from the wilderness it was natural that they should disappear as the forests were cut down, just like any other forest fauna.

The indigenous fauna increases in a land of aboriginal hunting folk of low culture, but decreases swiftly and surely in contact with civilized men. Aboriginal man is part of the fauna of a region. As a species he has struck a balance with other indigenous species of animals and as such is a ‘natural race’. Like the lower animals, the native man also vanishes from the region of settlement.[23]

By equating Indians with “lower animals”, the wilderness narrative dehumanized Indigenous people, and in all historical contexts, dehumanizing the “other” is the first step in man’s inhumanity to man. Ironically and in contrast, Algonquians viewed deer and other animals as their relatives! They had no received mandate for dominating the natural world or claiming superiority over other life forms. The wilderness narrative was the other side of the divine providence argument, expressed by John Winthrop in the 1630s—that the demise of Indians was a result of divine intervention favoring their replacement by the godly Puritans.[24]

Taming the wilderness was a pillar of “American Progress”, which was expressed in the concept of Manifest Destiny–that it was America’s destiny to expand as a nation and to dominate the continent.[25]

Taming the wilderness was a pillar of “American Progress”, which was expressed in the concept of Manifest Destiny–that it was America’s destiny to expand as a nation and to dominate the continent.[25]

The extinction and wilderness narratives were used to displace and then replace Indigenous people. It was seen as the natural order of things as sanctioned by God. In addition to taming the wilderness and glorifying colonial origin myths, the replacement process included changing Native place names and building on top of Native settlements, which usually were on the best land for growing crops and the most strategic locations for defense. Colonists typically built their first armories at the sites of Native watchtowers and fortifications, for example, which Edward Winslow described in explorations between 1622 and 1624. A likely example is Powder House Hill in Manchester-by-the-Sea, site of a Pawtucket fort defending the mouth of the Sawmill Brook at the harbor.[26]

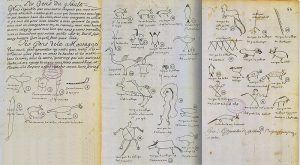

While some Native place names have survived, name changing began early through censorship of speech. In 1637 after defeating the Pequot in the Pequot War, for example, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made it a crime to speak the name Pequot. You could be whipped and fined or imprisoned for merely uttering the word. The Pequot were declared extinct, the village of Pequot was renamed New London, Connecticut, and the Pequot River was renamed the Thames. The Pequot were massacred at Mystic by joint colonial forces led by John Mason, with men from Cape Ann and Mohegan allies participating. The few survivors were sold into slavery. Renaming places and legally disbanding (or refusing to recognize) Native polities helped to legitimate replacement. At the time of European contact the Pequot numbered around 16,000. Today there are fewer than 2,000 Mashantucket and Eastern Pequot in Connecticut around Foxwoods and Stonington.[27] The Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Ledyard, Connecticut, recreates pre-Contact village life.

Present-day scholarship is exposing how New Englanders sought to erase Indigenous Peoples from both memory and landscape. Then, as now, history is written by groups in power. A new body of literature has arisen that aims to recover Native voices and ethnohistorical accounts of events previously defined, or erased, by those groups.[28] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, a Haitian anthropologist, wrote:

Historical narratives are premised on previous understandings, which are themselves premised on the distribution of archival power…. The archival power of local texts transformed what happened (a long and continuing process of colonialism and Indian survival) into that which is said to have happened (Indian extinction). Local texts have been a principal location in which this false claim has been lodged, perpetuated, and disseminated. The extinction narrative lodged in this archive has falsely educated new Englanders and others for generations about Indians, and it has been—and is still—used as an archival source itself, sometimes to be taken as factual evidence of Indian eclipse.[29]

Finding out that Indigenous Peoples lived on Cape Ann, learning about the archaeological, documentary, cartographic, and linguistic evidence for their presence here over several millennia, and discovering why we know so little about them, I turned to the task of reconstructing the human history of Cape Ann from the time when people first came here. Who were these peoples, where did they come from, and how did live here?

NEXT: What people lived in Essex County and when?

Notes and References

[1] See, for example, F. W. Putnam, On Indian remains in Essex County, Proceedings of the Essex Institute 5:186 (1867).

[2] An Algonquian platform pipe was taken from grave at Diamond Cove in Annisquam in 1919, for example, and exhibited at the Bronson Museum of Archaeology (today the Robbins Museum of Archaeology in Middleborough). In another published reference, “Judy Juncker [deceased, lived in Annisquam since the 1950s] remembers a skull, which was found at Norwood Heights in Annisquam and discarded by the builders. She knows that there were burial grounds there.” From p. 38 in The First People of Cape Ann: Native Americans on the North Coast of Massachusetts Bay by Elizabeth Waugh (Dogtown Books, 2005).

[3] In Ray, 2002, Gloucester Historical Time Line.

[4] For examples of “Erasure” in history, see a 2016 article by Prul Sehgal at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/07/magazine/the-painful-consequences-of-erasure.htmlConcept of erasure, and a 2021 article by Deondre Smiles at https://origins.osu.edu/article/erasing-indigenous-history-then-and-now?language_content_entity=en. Erasure can be applied to any event or outgroup and is a factor, for example, in Holocaust denial and failure to recognize the contributions of female scientists. See also Margaret Bruchac’s 2007 Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Historical Erasure and Cultural Recovery: Indigenous People in the Connecticut River Valley (UMI 3275817); and Nina Rothberg’s 2005 article, Native American Spatial Imaginaries and Notions of Erasure in Sherman Alexie’s The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fist Fight in Heaven, in Anamesa 3 (1), The Democracy Issue: 63-69. See also my article of August 8, 2020 on the historicipswich.org web site: Ancient Prejudice against “the Indians” Persists in Essex County Today.

[5] Bruen, Obadiah (1606-1681), 1650, Town Book (Gloucester, MA, 1642-1650), Manuscript transcription in the Cape Ann Museum and Gloucester Archives, Gloucester, MA. Thornton, John Wingate, 1854, The Landing at Cape Ann.

[6] Examples of Indigenous leaders’ cartouches on treaties and deeds may be found at the Salem Registry of Deeds web site for their Native American Deeds Collection, at https://www.salemdeeds.com/NAD/. See also Frederic Kidder, 1859, The Abenaki Indians: Their treaties of 1713 & 1717, and a vocabulary: with a historical introduction, at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25416/25416-h/25416-h.htm; and Vaughan, Alden T. and Deborah A. Rosen, eds., 1998, Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and Laws, 1607-1789: Vols 15-17: http://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/academic/upa_cis/Early%20American%20Indian%20Documents.pdf.

[7] Lamson, D. F., 1895, History of the Town of Manchester, Essex County, Massachusetts 1645-1895. Manchester, MA, p. 1.

[8] Currier, John J., 1902, History of Newbury, Mass. 1635-1902 (Vol. 1). Damrell & Upham, Boston MA.

[9] Pringle, James R., 1892 [p. 17 in the 1895 edition], History of the Town and City of Gloucester, Cape Ann, Massachusetts. (Self-published in Gloucester, MA, originally under the title Souvenir History of Gloucester Mass 1623-1892). The illustration is from the 1924 Book of the 300th anniversary observance of the foundation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony at Cape Ann in 1623 and the 50th year of the incorporation of Gloucester as a city, at the Sandy Bay Historical Society, Rockport, MA.

[10] Writing in 1634, Governor John Winthrop expressed the divine providence view of Indigenous “disappearance” through “pestilence” in his famous quote: “For the natives, they are near all dead of the smallpox, so the Lord hath cleared our title to what we possess.” See also C. Silva, 2011,Miraculous Plagues: An Epidemiology of Early New England Narrative, Oxford University Press, NY.

[11] and Felt, Joseph B., 1827, Annals of Salem, from Its First Settlement: https://archive.org/details/annalsofsalemfro00jose.

[12] Waters, Thomas F., 1905, Records and Dispositions of the Usurpation Period, Part I, p. 1, in Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Ipswich Historical Society, Ipswich MA.

[13] Ghere, David L., 1997, The “Disappearance” of the Abenaki in Western Maine: Political Organization and Ethnocentric Assumptions, Chapter 3, p. 72, in Calloway, Colin G., ed., After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England, Dartmouth College: 72-89.

[14] O’Brien, Jean M., 1997, “Divorced” from the land: Resistance and Survival of Indian Women in Eighteenth-Century New England. Chapter 6, p. 145, in Calloway, Colin G., ed., After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England: 144-161, Dartmouth College.

[15] Doughton, Thomas L., 1997, Unseen Neighbors: Native Americans of Central Massachusetts, A People Who Had “Vanished”, Chapter 9, pp. 207-208, in Calloway, Colin G., ed. After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England: 207-230, Dartmouth College.

[16] Jean M. O’Brien, 2010, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis MN.

[17] Cogswell’s address is reproduced in the pamphlet, Official Souvenir, 250th Anniversary; 1642-1892 Volume 1 (Gloucester MA).

[18] Archaeology was done in 1996 by Kathleen Wheeler and Myron O. Stachiw; reported in Excavations at Cogswell’s Grant in Essex, Massachusetts Historical Commission #1667.

[19] How the colonists saw the Indians (and vice versa) is taken up in more detail in other chapters.

[20] In 2022 a special commission voted to completely change the contemporary version of this seal, which still featured a defeated Indian (a Chippewa named Thomas Little Shell, who never lived in Massachusetts; the figure was drawn from his skeleton, preserved at Harvard, as a model) and to solicit public input for a new state seal and motto.

[21] Some sources include Daniel Gookin’s Historical Account of the Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians in New England in the years 1670-1677, and Neal Salisbury’s 2003, Embracing Ambiguity: Native Peoples and Christianity in Seventeenth-Century North America, in Ethnohistory 50 (2): 247-259: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/43368. For a less sympathetic perspective see the Puritan cleric Richard Mather’s treatise of 1653: Tears of repentance: or, A further narrative of the progress of the Gospel amongst the Indians in New-England: setting forth, not only their present state and condition, but sundry confessions of sin by diverse of the said Indians, wrought upon by the saving power of the Gospel; together with the manifestation of their faith and hope in Jesus Christ, and the work of grace upon their hearts. Related by Mr. Eliot and Mr. Mayhew, two faithful laborers in that work of the Lord. Published by the corporation for propagating the Gospel there, for the satisfaction and comfort of such as wish well thereunto. (London : Printed by Peter Cole in Leaden-Hall, and are to sold [sic] at his shop, at the sign of the Printing-Press in Cornhil, near the Royal Exchange.)

[22] Spencer Trotter, 1909, The Atlantic Forest Region of North America, Popular Science, p. 378.

[23] Trotter 1909, p. 387.

[24] See Note 10.

[25] This famous painting, “American Progress” by John Gast in 1872, shows “America” as a spiritually pure woman flying beyond the Mississippi River, displacing Indigenous people, include those forced to move west of the Mississippi after the Indian Removal Act of 1830. As you may recall from your United States history classes, the concept of manifest destiny was also used to justify national expansion through the annexation of Oregon, Texas, New Mexico, California Alaska, Hawaii, and the Panama Canal.

[26] Winslow’s description of Nanepashemet’s fort is in Part V of Mourt’s Relation (1632). Indigenous defenses are discussed further in the chapter on how the Pawtucket were organized and led.

[27] A primary account is Lion Gardiner’s (1660), Relation of the Pequot Warres, (Digital Commons 1901). Another is John Mason’s (Pau Royster, ed. 1736): Major’s Mason’s Brief History of the Pequot War: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/42. See also the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center at http://www.pequotmuseum.org/.

[28] A good example of the reinterpretation or rewriting of history and the factors involved is given in Ethan Schmidt’s 2013 article, Beyond the New England Frontier: Native American Historiography Since 1965, in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts 41, at http://www.wsc.mass.edu/mhj/pdfs/Beyond%20the%20New%20England%20Frontier.pdf.

[29] Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, 1997, Silencing the Past: Power & the Production of History. Beacon Press, Boston MA, p. 25.